🚨📰 Just out: "Legitimacy Challenges to the Liberal World Order: Evidence from UN Speeches"- w/ @ErikVoeten in Review of Int'l Orgs

We put current legitimacy challenges of int'l economic institutions in a half-century context.

A thread.

✅ Open access:

doi.org/10.1007/s11558…

We put current legitimacy challenges of int'l economic institutions in a half-century context.

A thread.

✅ Open access:

doi.org/10.1007/s11558…

Global economic institutions currently find themselves on the firing line, whether from anti-liberal states or from populists/nationalists in liberal democracies.

But this is not the first time they have attracted intense criticism and challenges to their legitimacy.

But this is not the first time they have attracted intense criticism and challenges to their legitimacy.

To understand these processes, we examined world leaders' speeches on the podium of the UN General Assembly.

We spotted references to liberal economic institutions, and created a coding scheme drawing on Albert Hirschman’s 'exit, voice and loyalty' typology.

What did we find?

We spotted references to liberal economic institutions, and created a coding scheme drawing on Albert Hirschman’s 'exit, voice and loyalty' typology.

What did we find?

First, the proportion of speeches that criticize international economic institutions has decreased over time.

Heyday of rhetorical challenges was in late-1970s (see New Int'l Econ Order); since then, stable decline.

Exit threats and explicit endorsements have been scant.

Heyday of rhetorical challenges was in late-1970s (see New Int'l Econ Order); since then, stable decline.

Exit threats and explicit endorsements have been scant.

More than reflecting notable trends in criticism or loyalty, a defining feature of the past decade is that only less than half the speeches devote any attention to global economic institutions.

Most leaders are simply silent about the liberal order.

Most leaders are simply silent about the liberal order.

What do leaders talk about when they refer to the order?

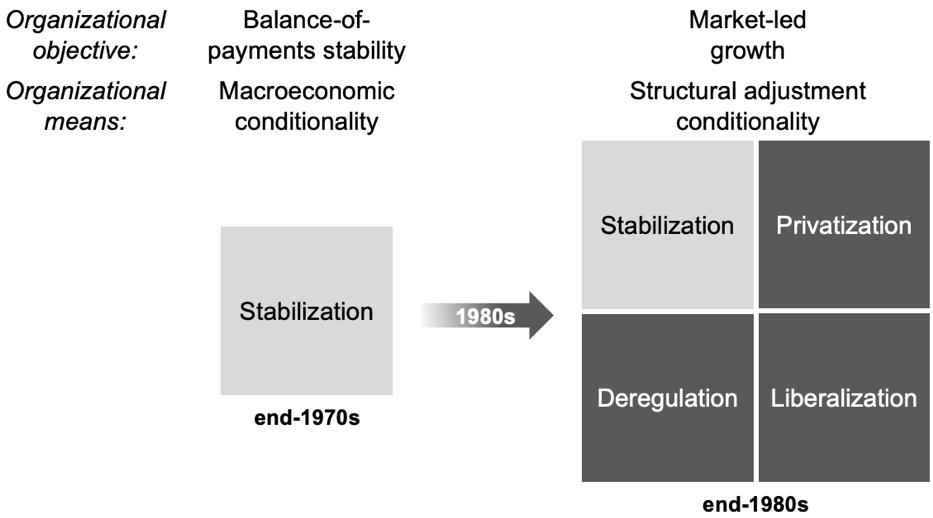

We see changes over time: references to sovereignty and inequality were prominent in 1970s & 80s, debt and conditionality in the 1990s & 00s, and more recently we see some references to climate change.

We see changes over time: references to sovereignty and inequality were prominent in 1970s & 80s, debt and conditionality in the 1990s & 00s, and more recently we see some references to climate change.

Who criticizes?

We find a broader transformation in the nature of contestation away from the Cold War insider-outsider conflict and towards insider contestation (that is, by countries that have already liberalized their domestic economies).

We find a broader transformation in the nature of contestation away from the Cold War insider-outsider conflict and towards insider contestation (that is, by countries that have already liberalized their domestic economies).

Leaders of economically-open countries expressed more support for global economic institutions during the Cold War but less support since.

More recently, contestation primarily revolved around rules and practices rather than the order itself.

More recently, contestation primarily revolved around rules and practices rather than the order itself.

Where does this leave us?

Given current narratives about the fragility of the liberal world order, we set to study legitimacy challenges.

We find evidence of changing nature of contestation, but we also find that a defining feature of recent decades is silence about the order

Given current narratives about the fragility of the liberal world order, we set to study legitimacy challenges.

We find evidence of changing nature of contestation, but we also find that a defining feature of recent decades is silence about the order

Why is criticism of the liberal world order in the UNGA at an all-time low?

Our analysis points to three directions: political preferences of leaders, broader geopolitical shifts, and institutional inertia as the order has acquired a taken-for-granted quality.

Our analysis points to three directions: political preferences of leaders, broader geopolitical shifts, and institutional inertia as the order has acquired a taken-for-granted quality.

Does this mean that the current challenges to the liberal order are a blip? No.

It matters a lot that the order’s main protagonist, the US, is now among its fiercest critics. But that might change to some degree if a new president is elected.

It matters a lot that the order’s main protagonist, the US, is now among its fiercest critics. But that might change to some degree if a new president is elected.

More importantly, the liberal international order has not been able to effectively respond to multiple ongoing crises: environmental, health & economic.

Unrest is brooding and legitimacy challenges—whether by politicians, civil society or even business interests—are intensifying

Unrest is brooding and legitimacy challenges—whether by politicians, civil society or even business interests—are intensifying

These challenges have not forcefully made their way to the podium of the UNGA — yet!

It is possible that the decline in criticisms towards the liberal world order that we document only reflects the calm before the approaching storm.

It is possible that the decline in criticisms towards the liberal world order that we document only reflects the calm before the approaching storm.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh