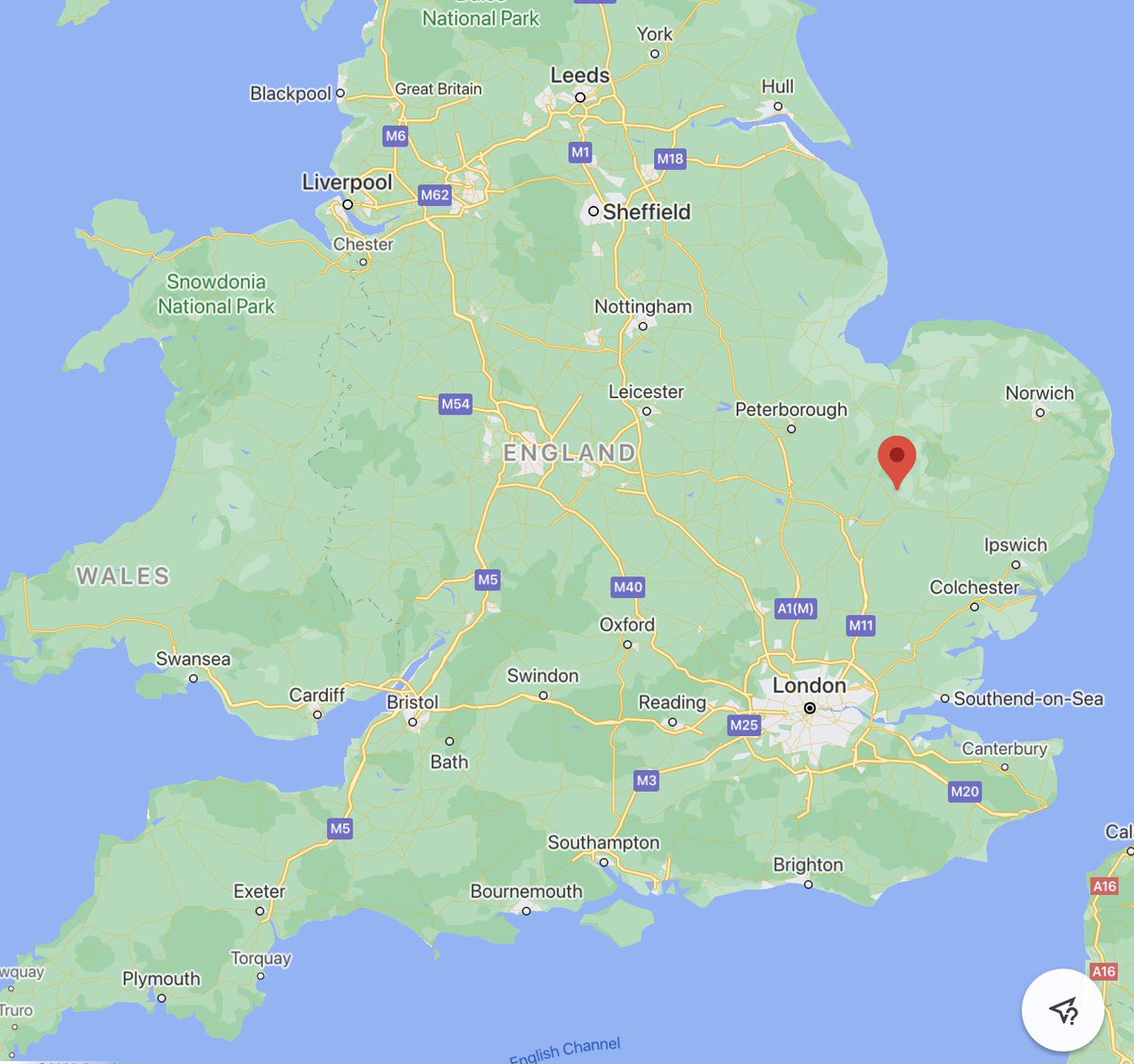

THREAD. Here’s a story about how I went looking for the obvious in a landscape and found something much more interesting. The place was Isleham, on the NE Cambs fen-edge & the initial hook was an early 12thC chapel, almost all that remains of a Breton priory..

2. ...founded within a generation of the Conquest. Today, only the priory chapel remains. It was converted into a barn & remained in agricultural use until the mid-20thC.

british-history.ac.uk/vch/cambs/vol1…

british-history.ac.uk/vch/cambs/vol1…

3. The lovely chapel is said to be ‘the best example in the country of a small .. substantially unaltered.. Benedictine priory church’. Its original 12th-century walls all survive; the raised nave roof is the only major change. More interesting tho ... english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/i…

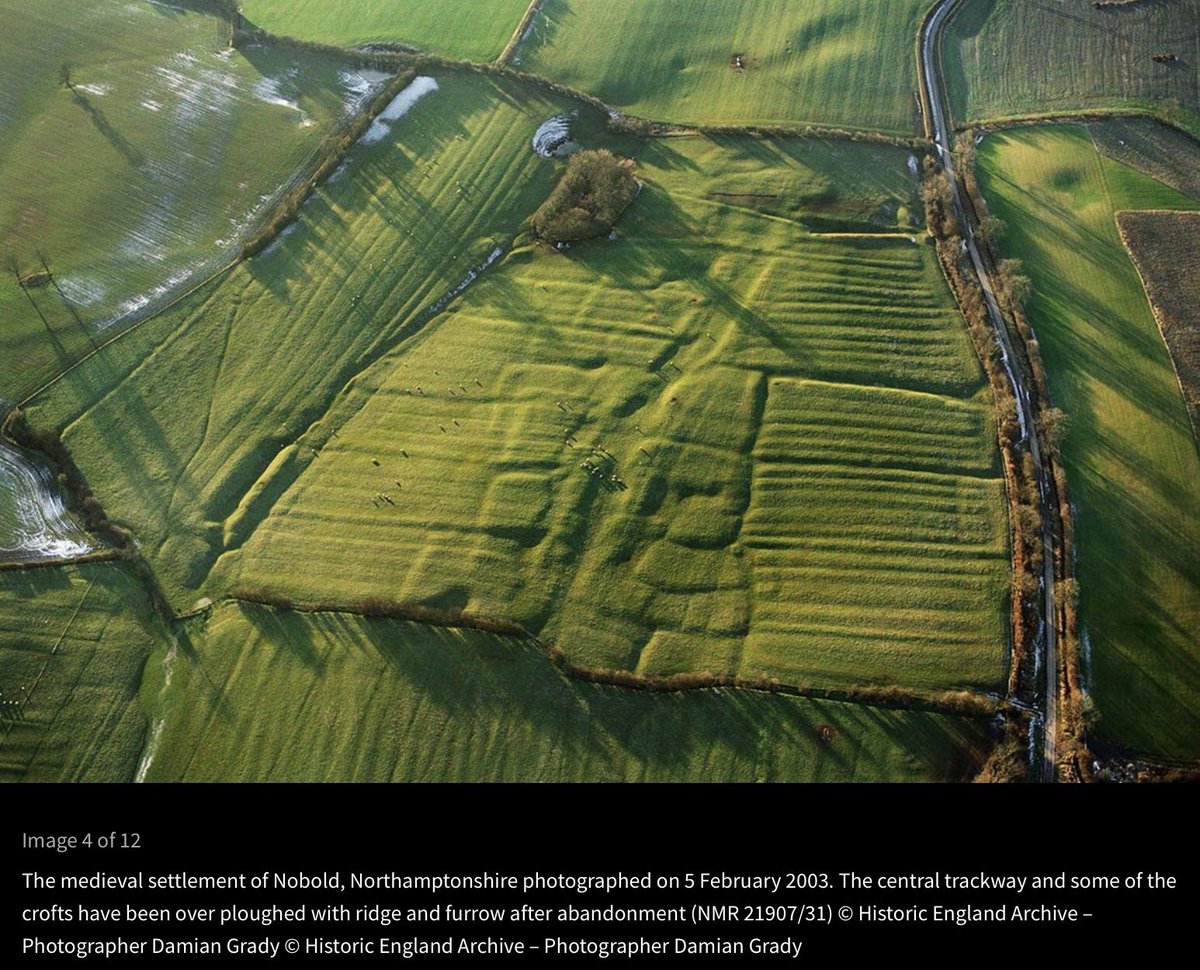

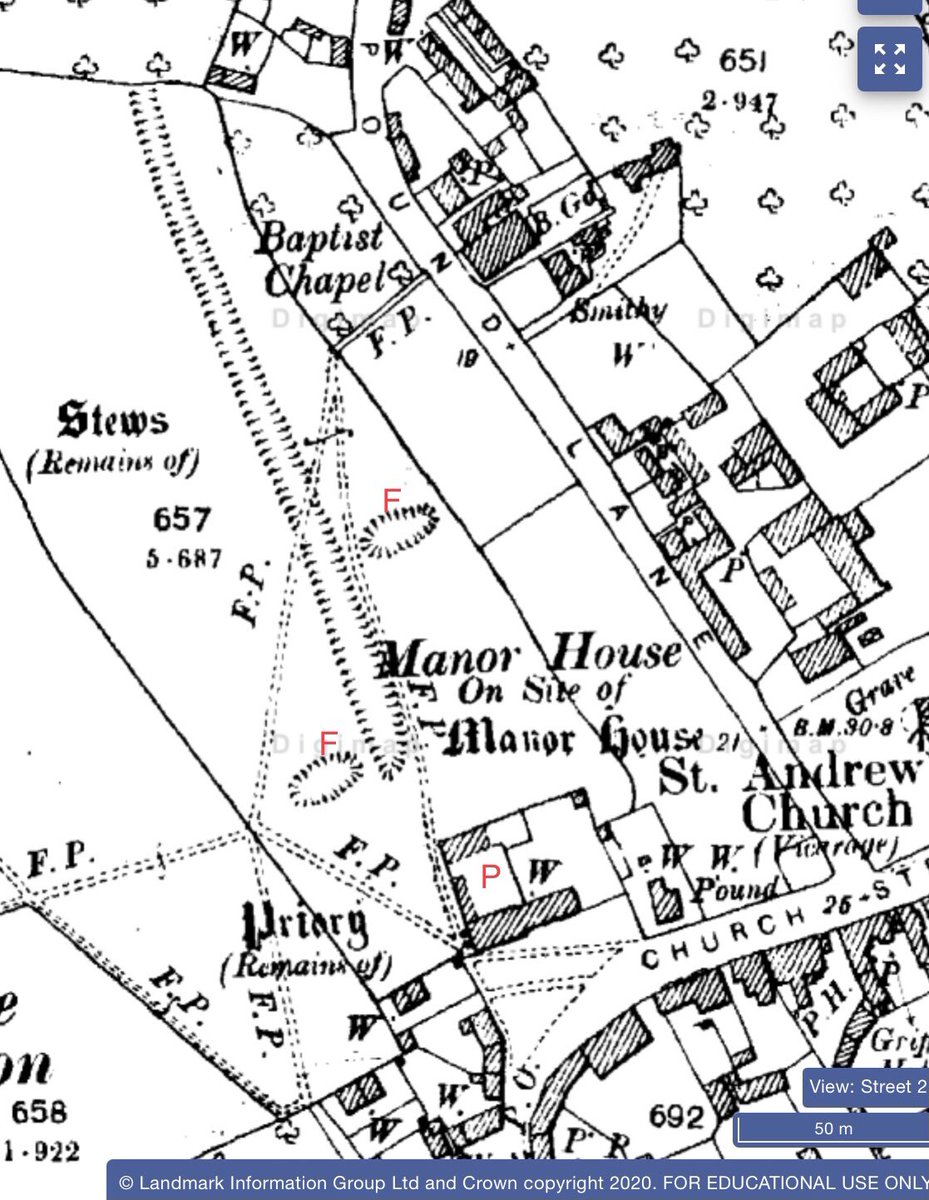

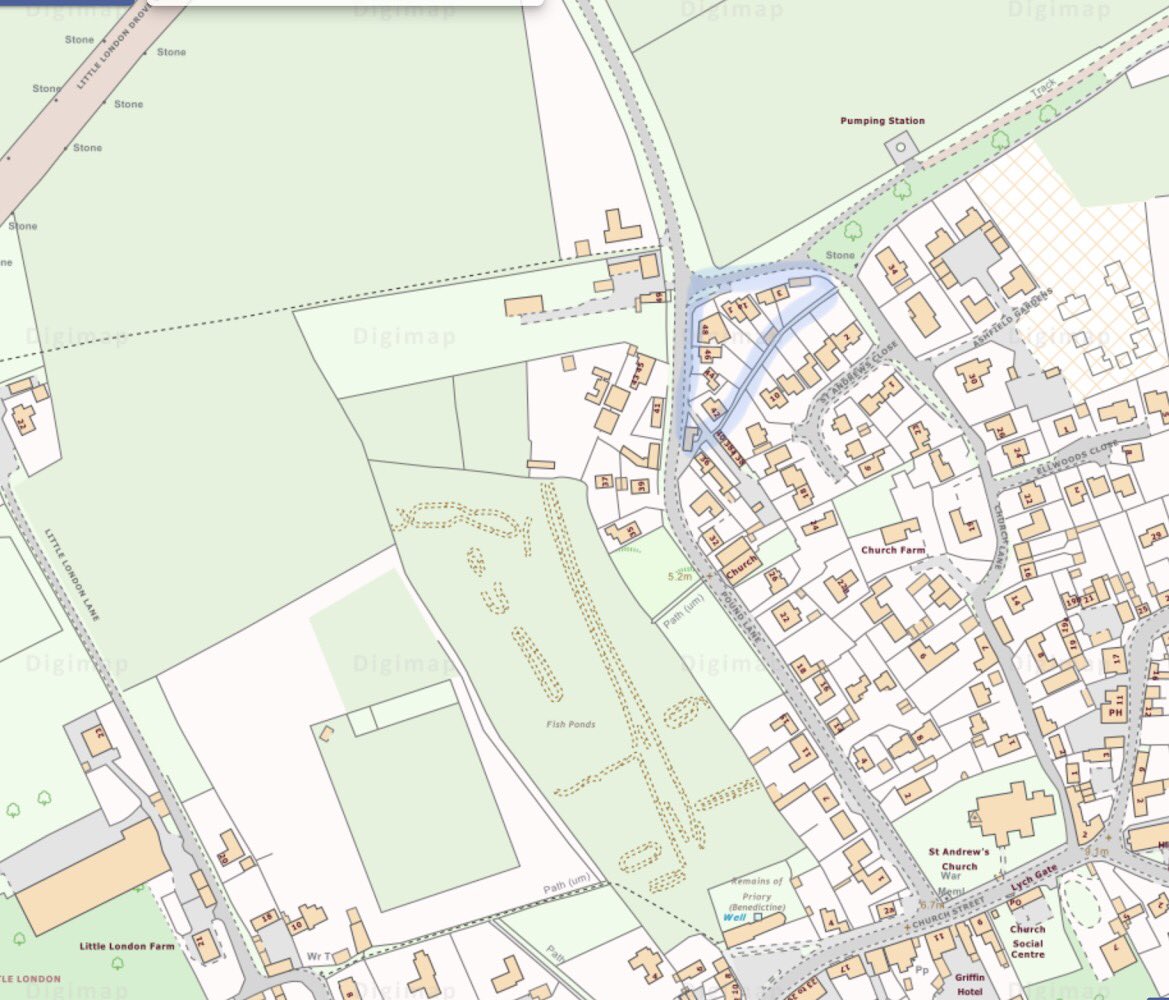

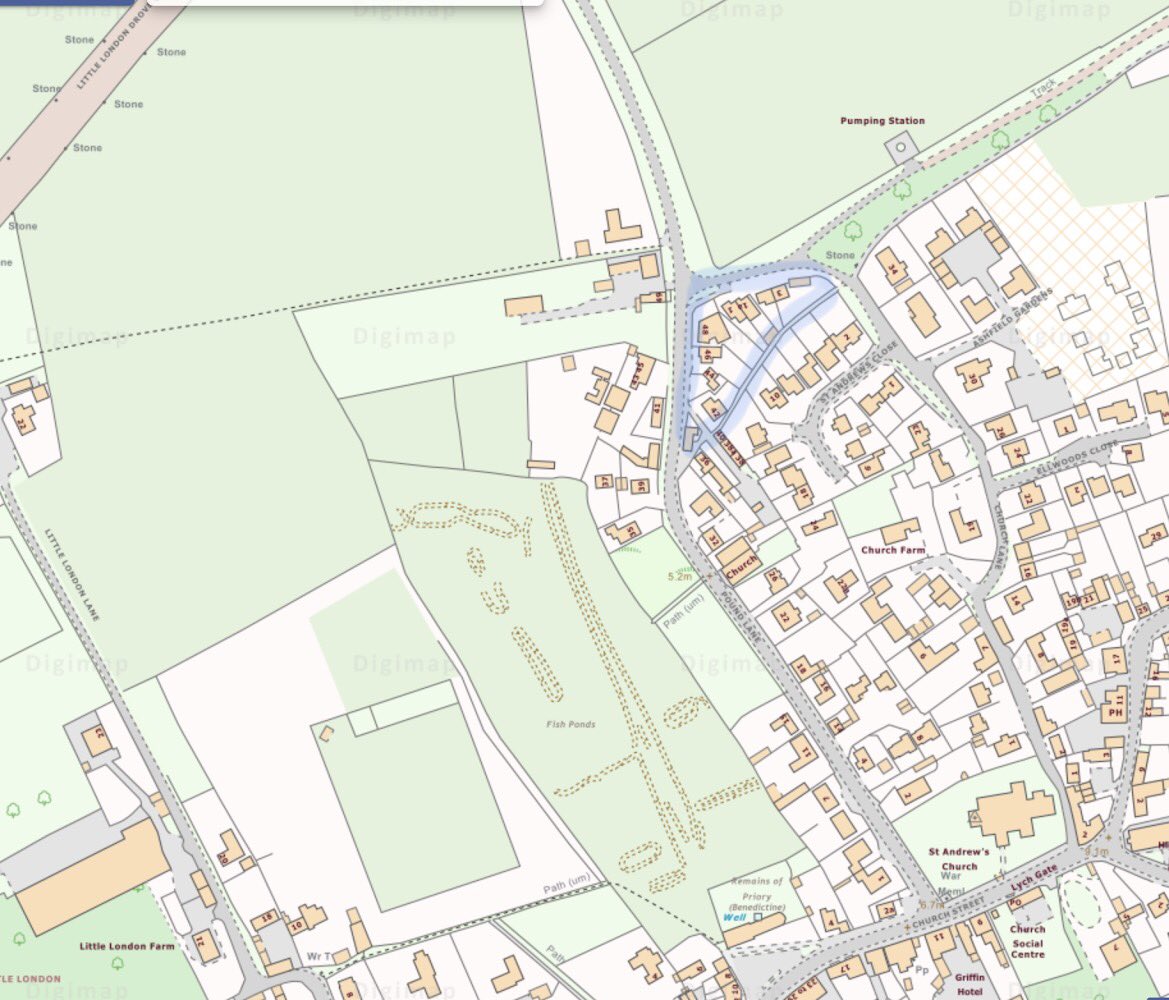

4. ... was the field behind the chapel whose earthworks preserve some of the priory’s activities. What were they? The OS described them as fishponds (also called stews), but they didn’t all look like fishponds. There were roughly rectangular depressions (marked F on the map) ...

5. ... that although now dry probably once looked something this fishpond at Baddesley Clinton. What I didn’t understand was how the long narrow feature running down the length of the field could be a fishpond.

6. It is a depression, it’s true, but I wasn’t convinced by the fishpond interpretation. So I carried on exploring the village and came across several more features that were just as puzzling. I’ll describe them in turn and come to explanations in a while.

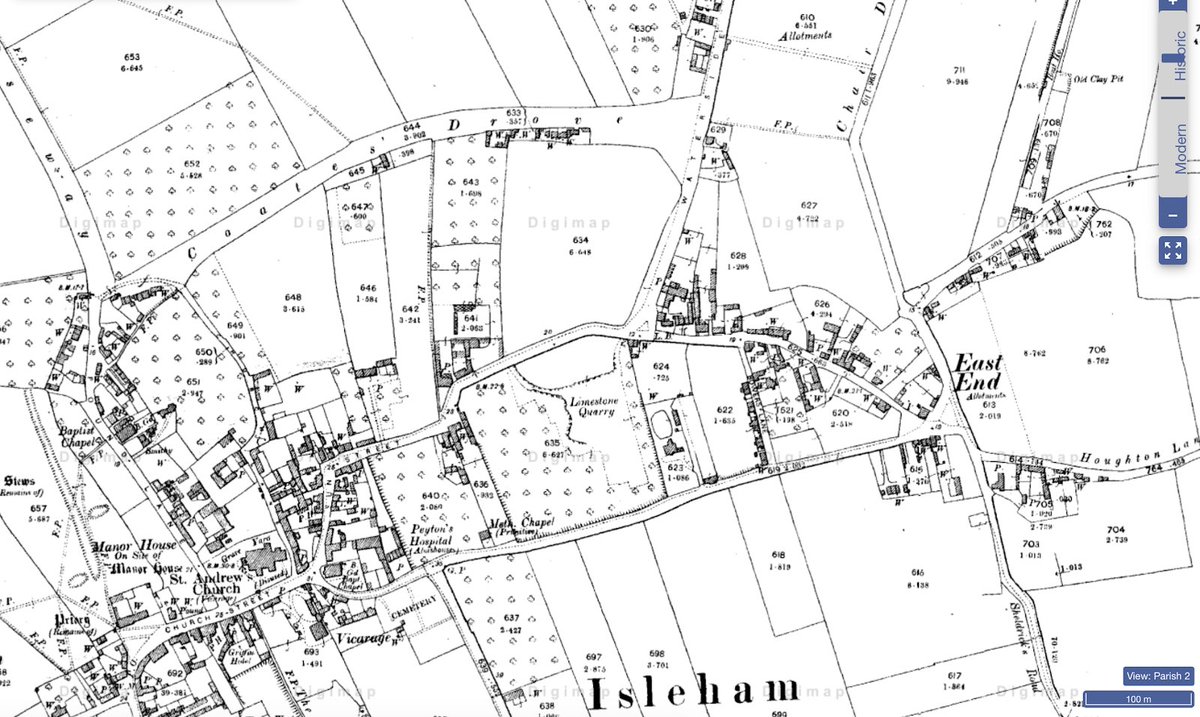

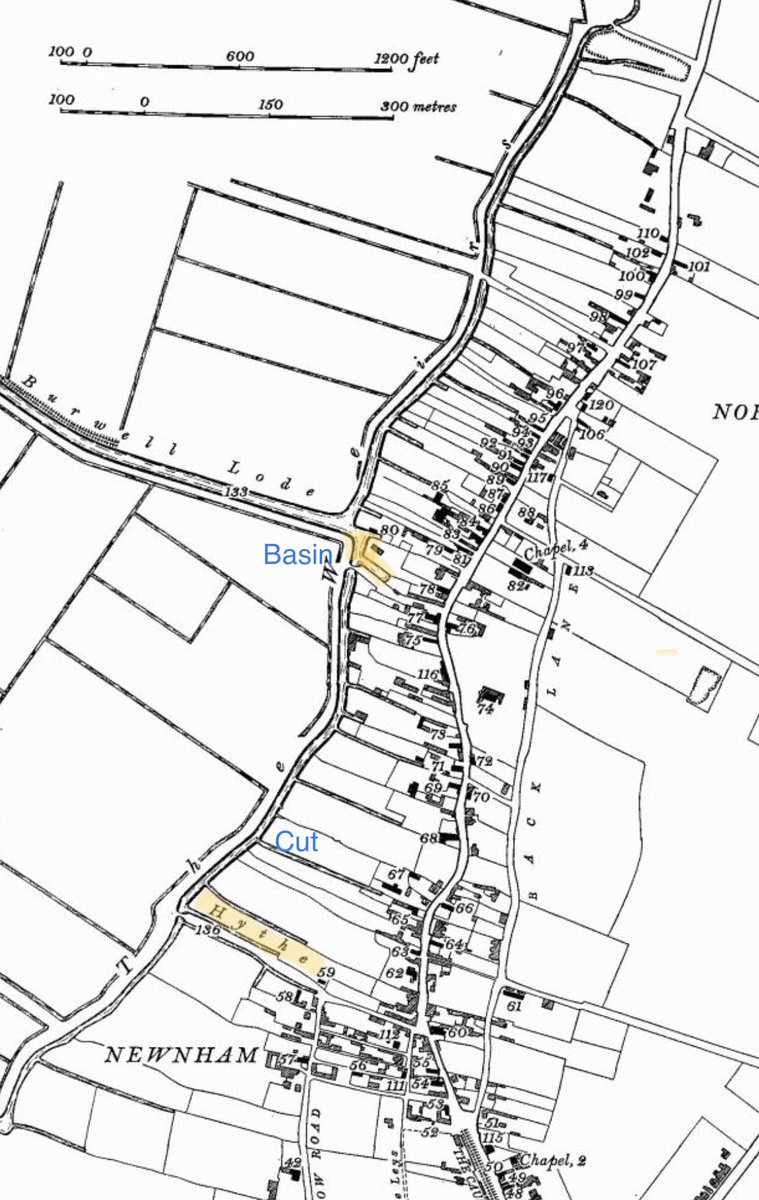

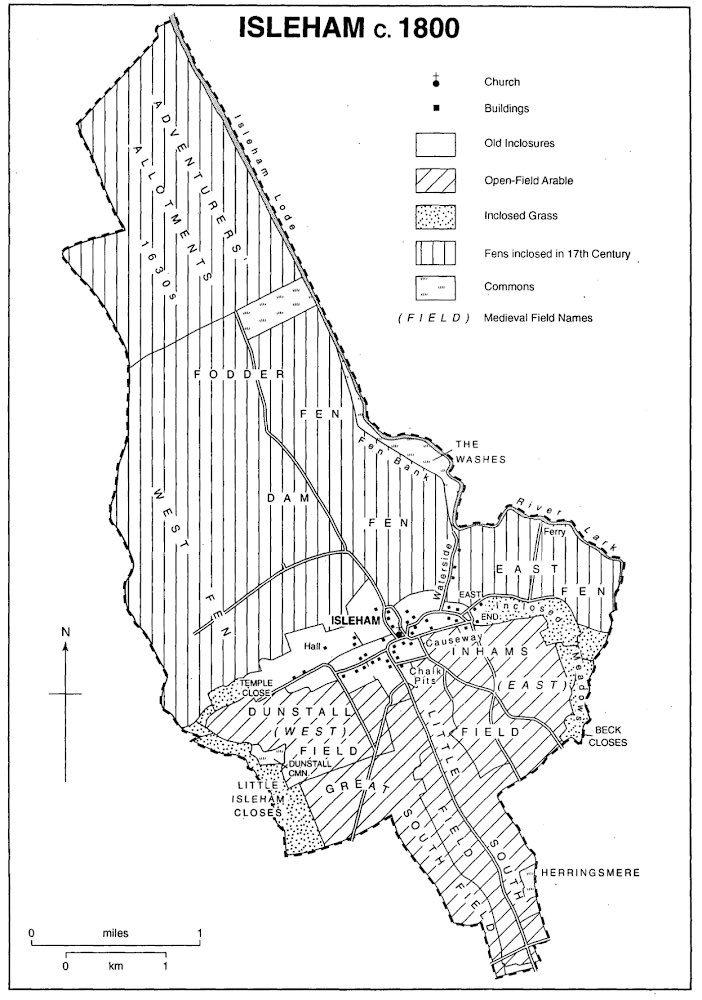

7. Here’s the earliest map of the village, made c1800, with the locations of each of the features marked on it, alongside the IS map of about 1900, so you can follow my explorations. The priory chapel is at C.

8. My next stop was at the bottom of Pound Lane, where a row of 19thC cottages appeared to have been built into a roughly D-shaped depression (B on the old map). The cars were all parked on the downward-sloping verge.

9. Around the back, their gardens lay at least a metre below the surface of the public footpath that ran along their back boundaries. Substantial brick buttresses prevented a small barn belonging to one of the cottages from subsiding into the depression. (Not visible in photo)

10. The next puzzle was revealed when I turned around, with my back to the public footpath sign. The footpath along the back of the houses continued eastwards across the road (Church Lane), running just to the L of the hedge. Why did follow a ditch when ..

11. .. there was a perfectly good, much wider unpaved road (Coates Drove) just to its L (ie on its northern side) which followed higher ground?

Well, I followed Coates Drove eastwards where it ended in ..

Well, I followed Coates Drove eastwards where it ended in ..

12. ..a large triangular green. You can just see Coates Drove entering it between the trees and the clipped hedge in the far distance . And the footpath still ran along the ditch. That ditch was unusual.

13. Most ditches have a symmetrical profile - a u or a v. This one sloped at a much shallower angle on one side, towards the green, than it did on the other, which followed a much steeper angle.

14. And finally, as I turned for home, this road sign caught my eye. Waterside. But the road didn’t run alongside any water. What was (or had been) going on?

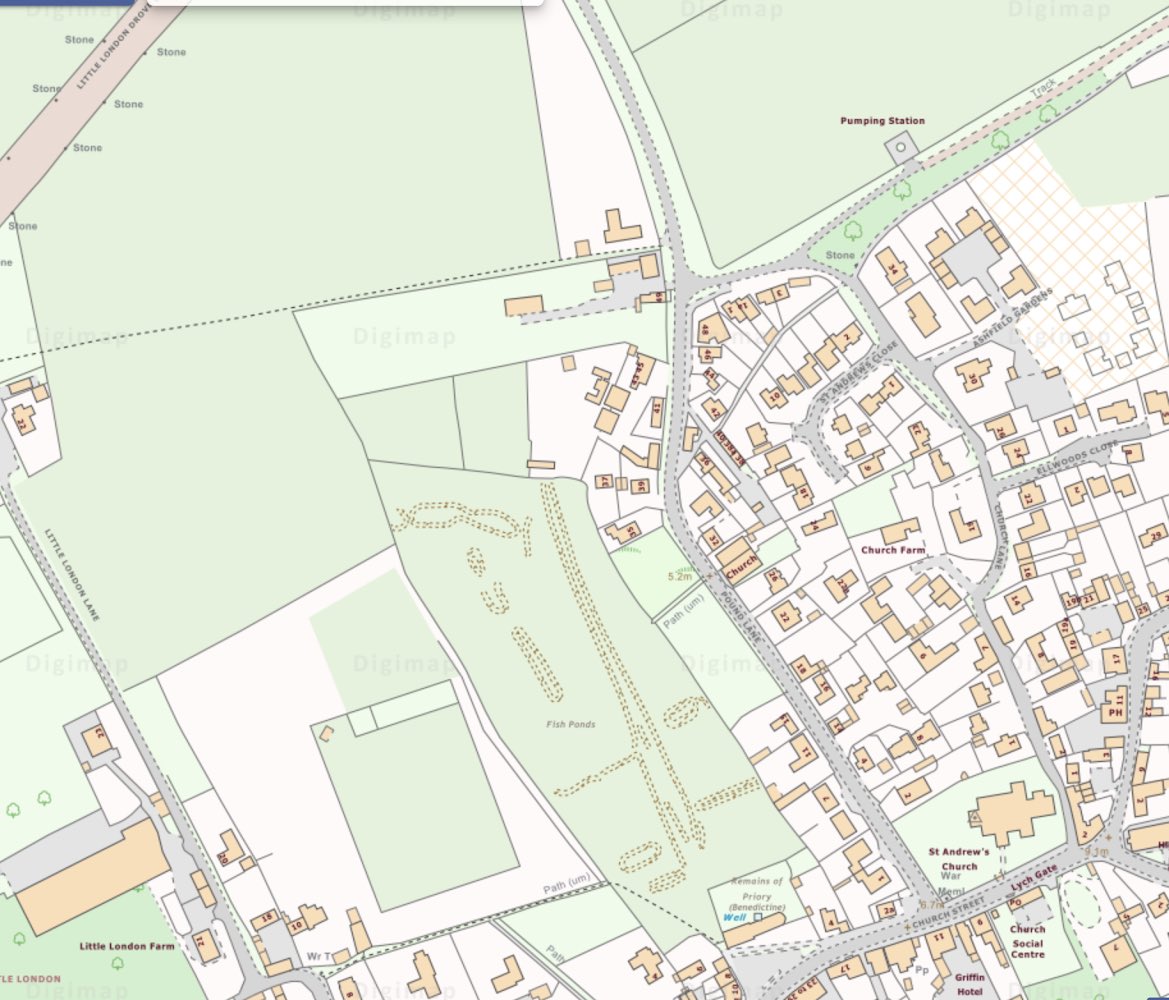

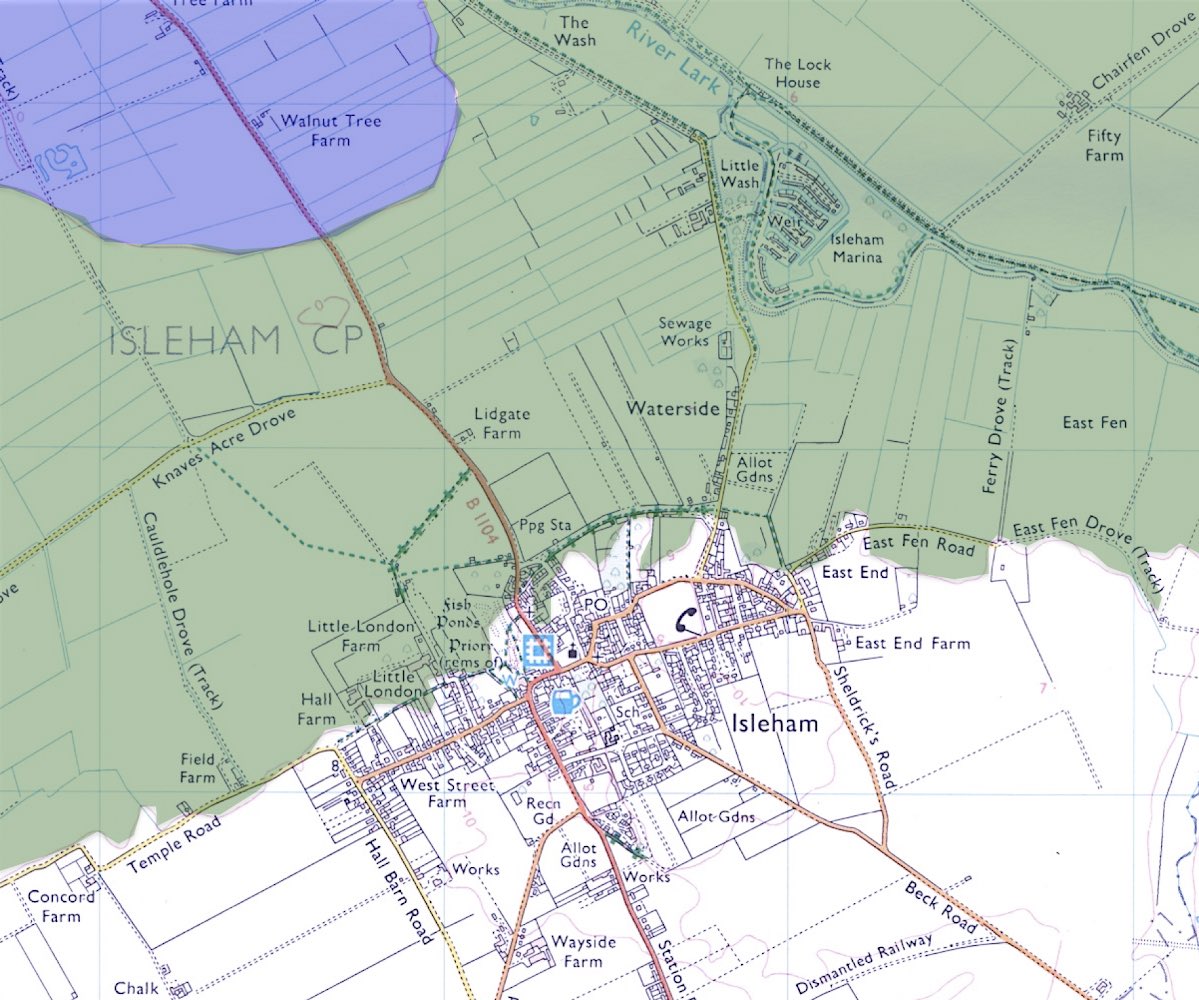

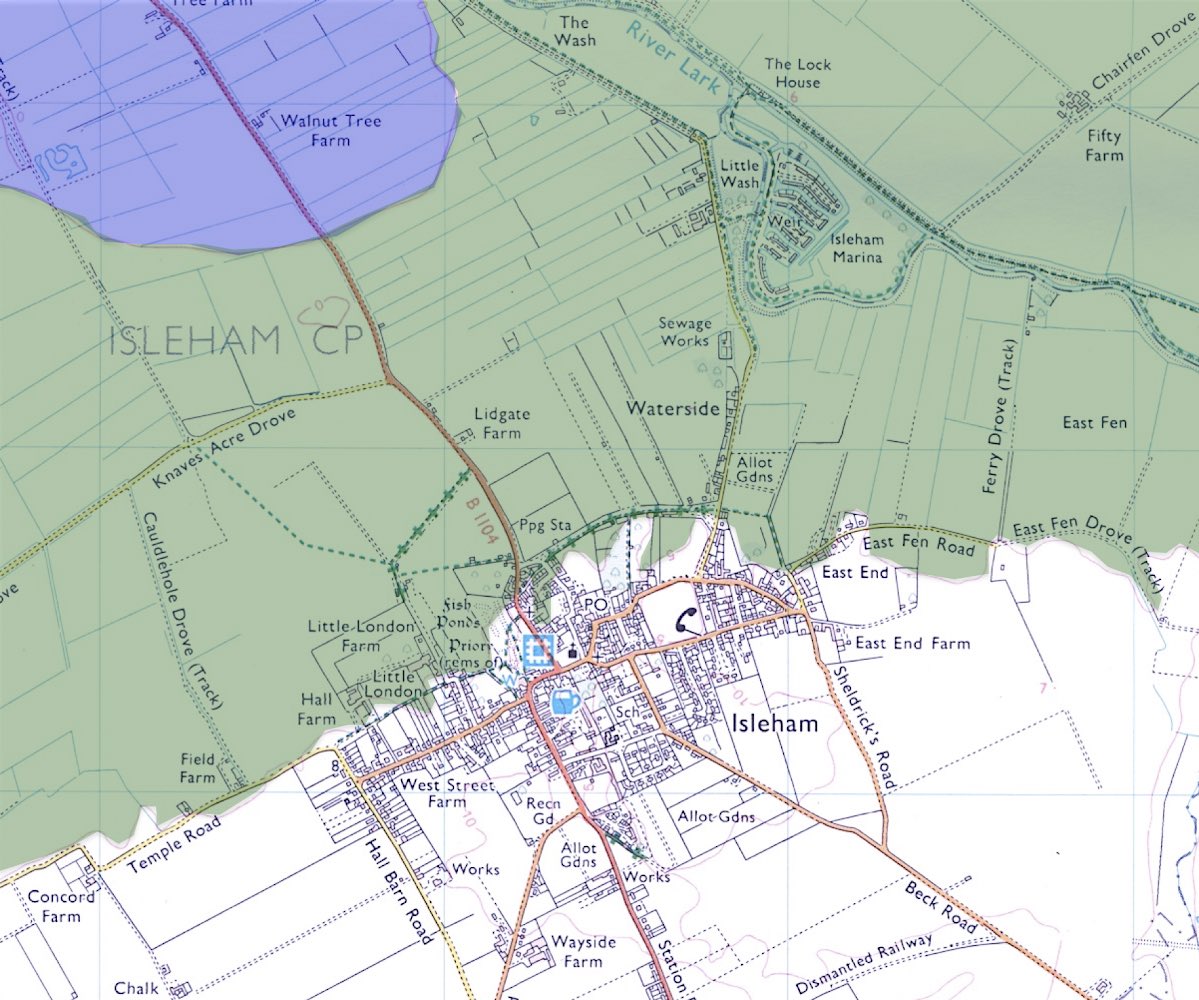

15. I went home and played with maps. Here’s the modern OS map of Isleham - you can see the Priory & Waterside on it. Land that was flooded in winter is coloured in green - it lay between sea level and about 5m above see level. You can see how the village follows it.

Land that lay below sea level was, before drainage, permanently under water and is coloured in blue. Both colours refer to the period before drainage, which began on the green-coloured area in the mid-17thC. The map thus shows early modern, medieval & earlier wetland water levels

17. Colouring the map made me realise that I’d seen this before. At Burwell, for example, catchwater drains ran along the fen-edge connecting basins, hythes and cuts to the lode (the canal) connecting the fen-edge with the River Cam british-history.ac.uk/rchme/cambs/vo… (Monument 133).

18. There’s more detail on lodes, catchwaters and how they work here:

https://twitter.com/DrSueOosthuizen/status/1144938005779664897

19. While these systems survive at places like Burwell, it seemed that what I’d come across at Isleham was a relic of what had once been. So let’s go across the village again, looking at each site but this time moving from east to west - from Waterside back to the Priory.

20. And I should have said earlier: E = Waterside, A = ditch with unusual profile, D = Coates Drove. As you already know, B = houses built in the depression, and C = The Priory.

21. Waterside (E) once ran alongside a canal (Isleham Lode) a major cut connecting the fen-edge with the River Lark. The section of the lode near the village has been filled in but survives in a large modern drain a little way N of the village, that eventually feeds into the Lark

22. The large triangular green (A) was, I think, once a water-filled basin in which boats could load/offload. The clues lie in (1) its uneven surface showing that it had eventuallly been filled in; (2) in the oddly shallow slope of its S ditch - as if it had been filled in ...

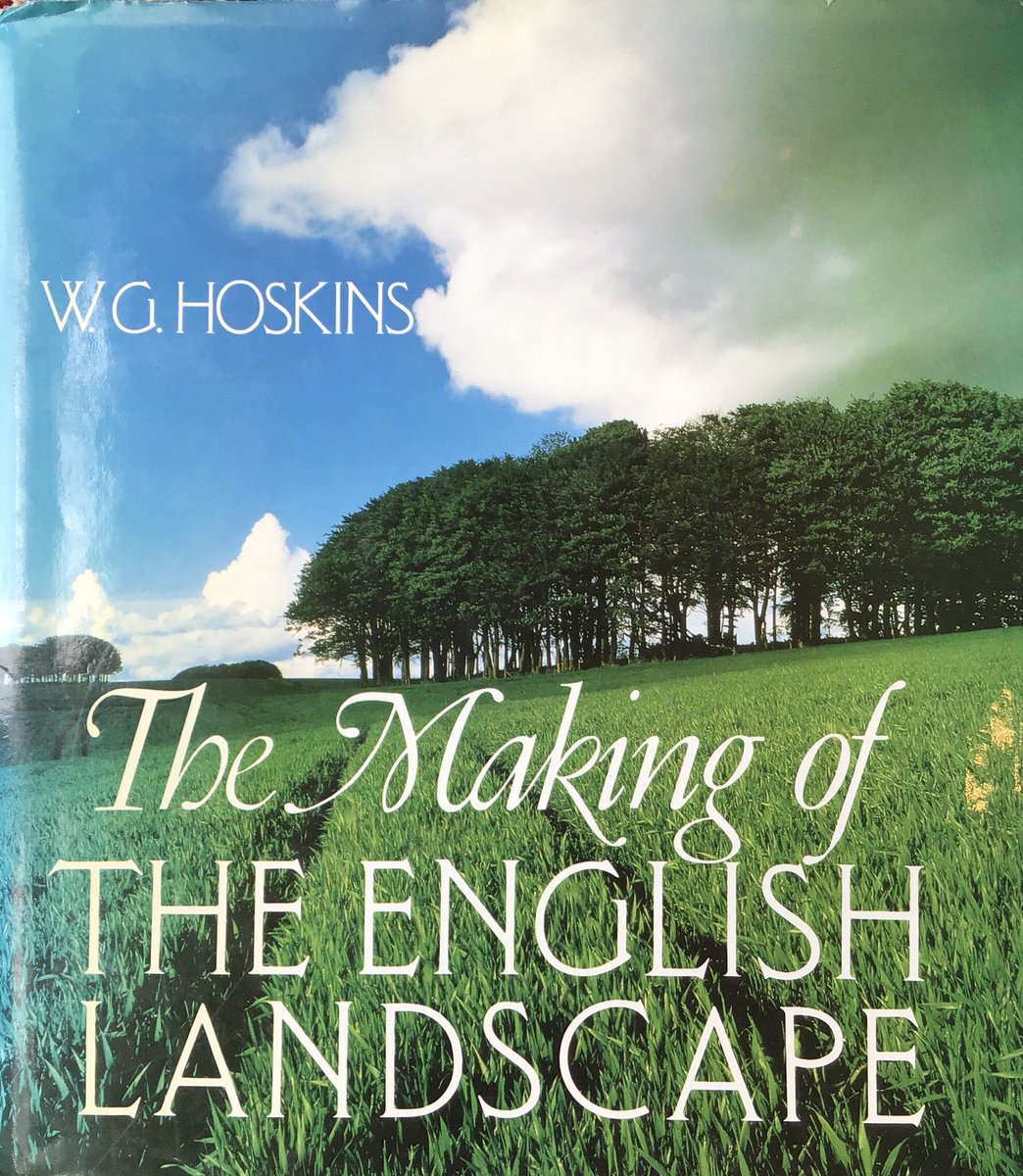

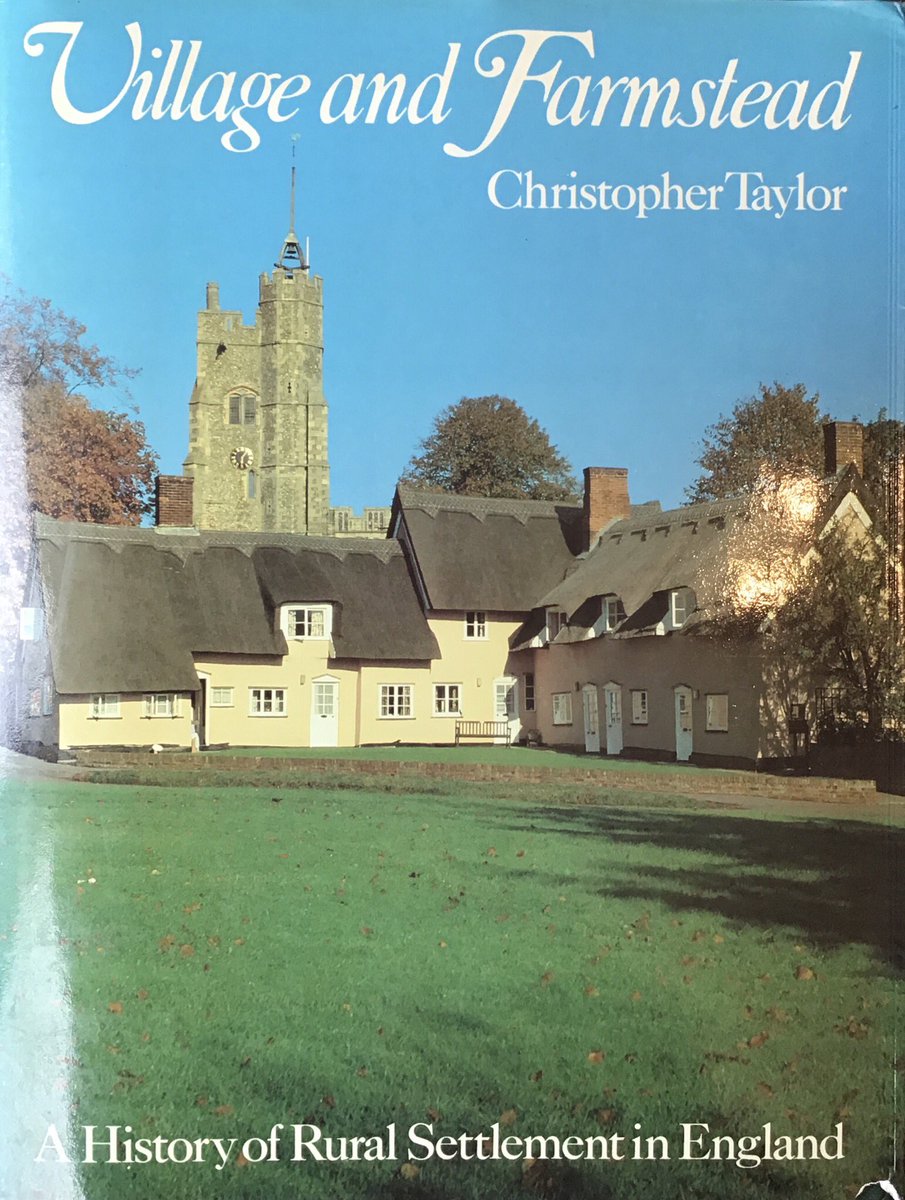

23. .. so that the ditch along its edge was preserved; and (3) the ditch itself - all that remains of the catchwater drain which once looked like this one at Reach. AND still a public right of way, just as the catchwater had also been too.

24. That footpath - once the catchwater - can be followed most of the way along Coates Drove to the house-filled depression (B) at the bottom of Pound & Church Lanes. It, too, was once a basin for boats, & the public footpath & the drove lie on the banks that once defined it.

25. The catchwater survives westward in property boundaries & on air photos - further than we’ll go today. Its presence explains the long hollow depression: the Priory’s (C) own private cut enabling the monks via catchwater, basins, lodes & rivers, and the sea...

26. The whole system revealed as a means of carrying agricultural produce both to home farms, and export to local, regional, national and international markets. Imports were as important - the chancel arch in the Priory is made from Caen stone, after all.

27. The thrill of landscape history is in understanding the meaning of these small, everyday, apparently insignificant features. It’s worth saying, too, that the RCHME’s work on Reach & Burwell was essential - underscoring the value of reading as widely as possible 🤗. END

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh