Thread: Now forthcoming in Public Choice: how rent-seeking explains asylum expansion in America between 1870 and 1910 (co-authored with Ray March). #econhist #econtwitter

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

Few people know that the asylums in American asylums expanded 10x in terms of absolute numbers and close to 4x in per capita terms between 1870 and 1910.

Most works in social history attribute this to broadly defined contemporary understandings of public interest (some of which are less savoury than others). Very few works have tried to see if there was a rent-seeking component. Ray and I argue there was one!

In fact, we argue that the rent-seeking forces complemented public interest forces in that they were necessary ingredients to secure a political coalition to expand asylums.

Who were the rent-seekers? Asylum physicians who were a) redirecting care towards them and away from private providers and local poorhouses (who catered to heterogenous pops); b) secured a privileged relationship with state governments in order to increase funding/demand

How do we test this? We argue that asylum physicians were as strong a rent-seeking force as the broad profession of medicine.

If physicians in state i were unable to obtain an entry barrier (examining board, registration law etc.), asylum physicians were unable to obtain restrictions against private providers, secure the transfer of insane from poorhouses and secure extra funding.

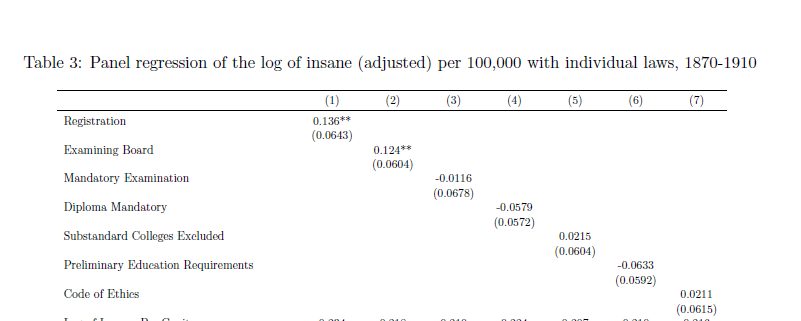

IOW, medical laws are a proxy for rent-seeking. We also single out examining boards as the most important laws because they truly restricted entry into the profession. We use those laws as our variable of interest in a difference-in-difference setup.

What we find confirms what qualitative sources discuss: rent-seeking did play a role especially with the crucially important "examining board" variable.

However, while the pattern is robust to numerous alternative specifications, the effect do not explain more than two-fifths of the increase in institutionalization. This is why we say that rent-seeking is a complement.

Asylum physicians were a bit like the bootleggers in the "bootleggers and baptists" theory of regulation. Both the high-minded (baptists) supporters and the narrowly self-interested supporters (bootleggers) are necessary to secure the regulation.

In our case, the bootleggers are the asylum physicians and the baptists are progressive social reformers who were genuinely concerned with the welfare of the insane.

In this, we follow in the line of the work of Peter Leeson (in this great piece in European Journal of Law and Economics -- cc. @alain_marciano link.springer.com/article/10.100…) who argues that "public interest" can complement "rent-seeking" in explaning regulations/state interventions

This paper, by the way, is the second in a series (with Ray March) on visiting the political economy and economic history of eugenics in America (next on our list is the topic of how sterilization laws were adopted).

CC. @MarkKoyama @palssonc @MarketPowerYT @WarrenAnderson9 @econhist_allday @Aly_Meek @kingsatwestern

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh