I teach a Critical Appraisal course to seniors in Exercise Science & Pre-Health. Our 1st project is to redo a published meta-analysis. Students always find errors of various degrees of severity. But yesterday, they hit the jackpot. A meta that is so made-up, it's funny. A thread.

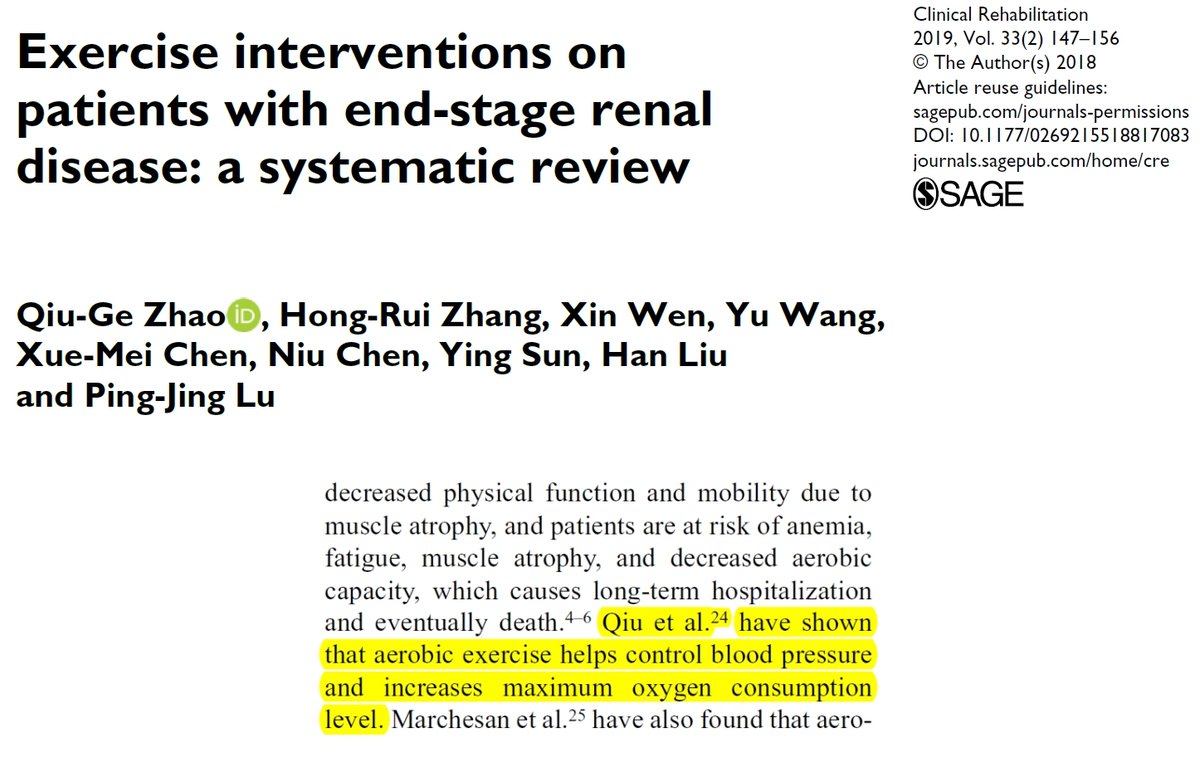

The paper is published in "BioMed Research International," a @Hindawi journal indexed in PubMed, and has been cited 39 times in 3 years as having shown that exercise benefits patients with end-stage renal disease (e.g., see below). pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28316986/

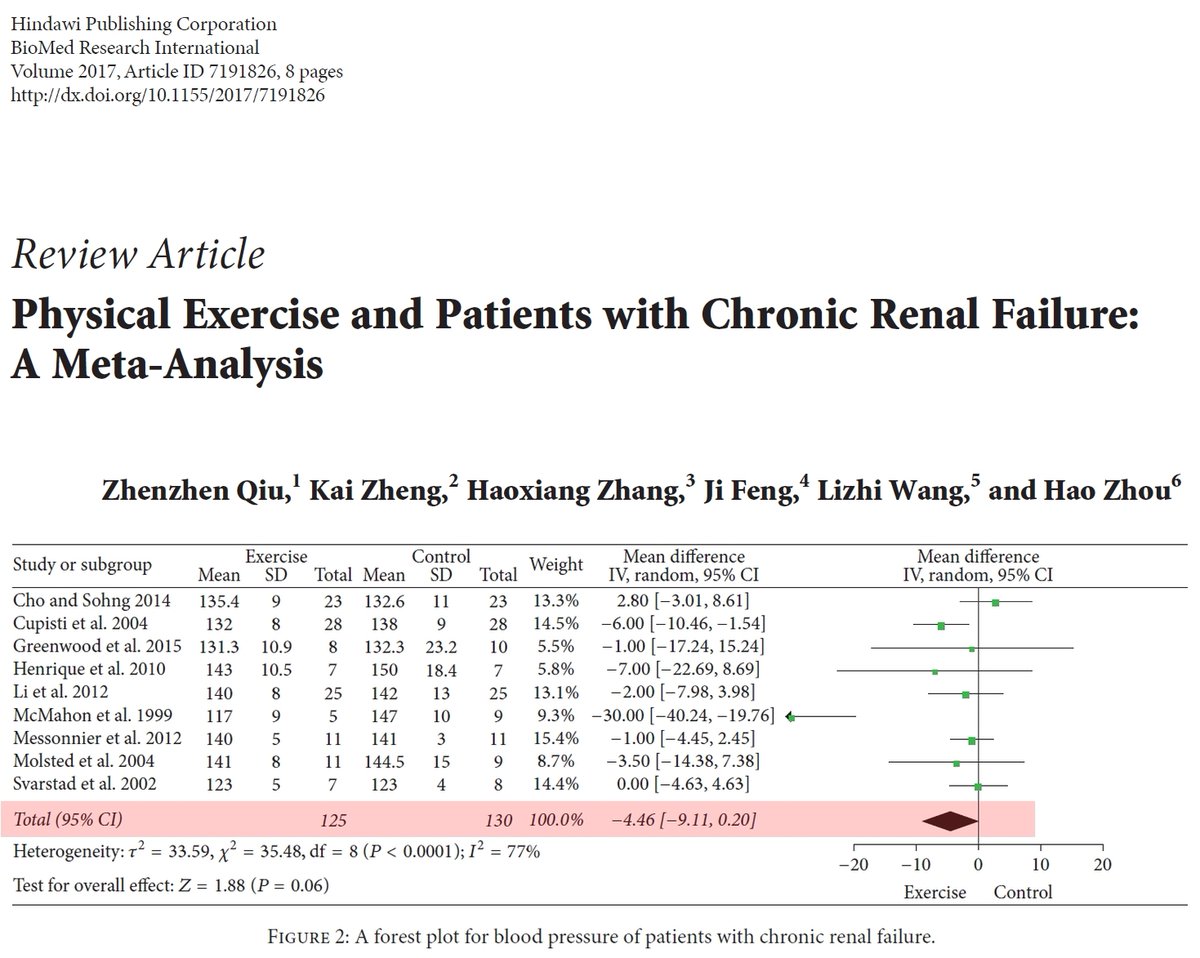

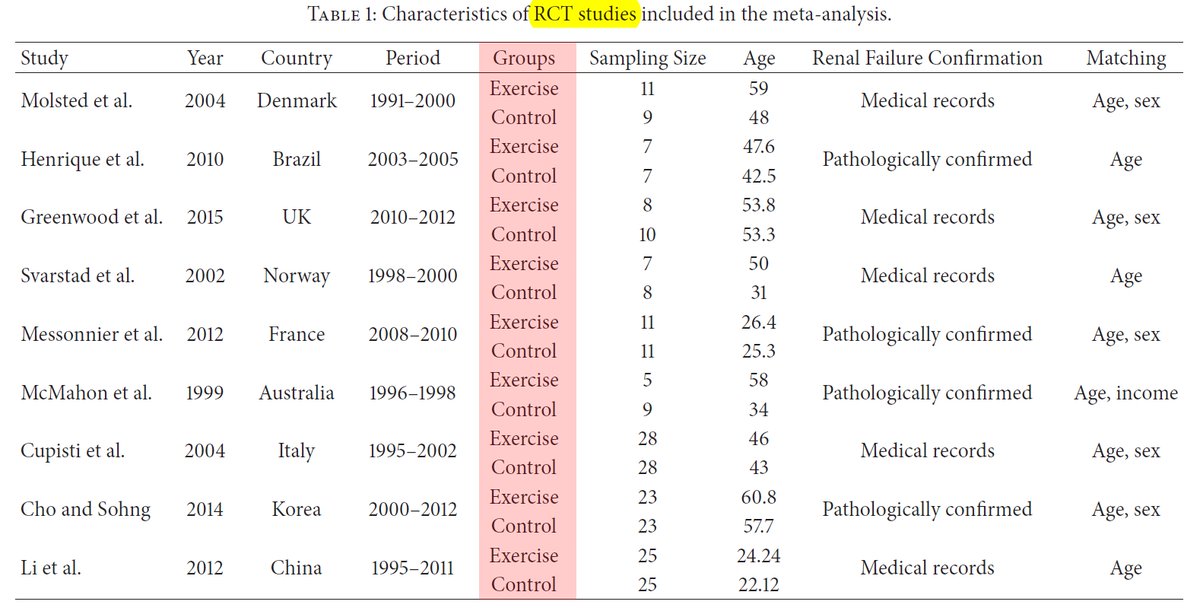

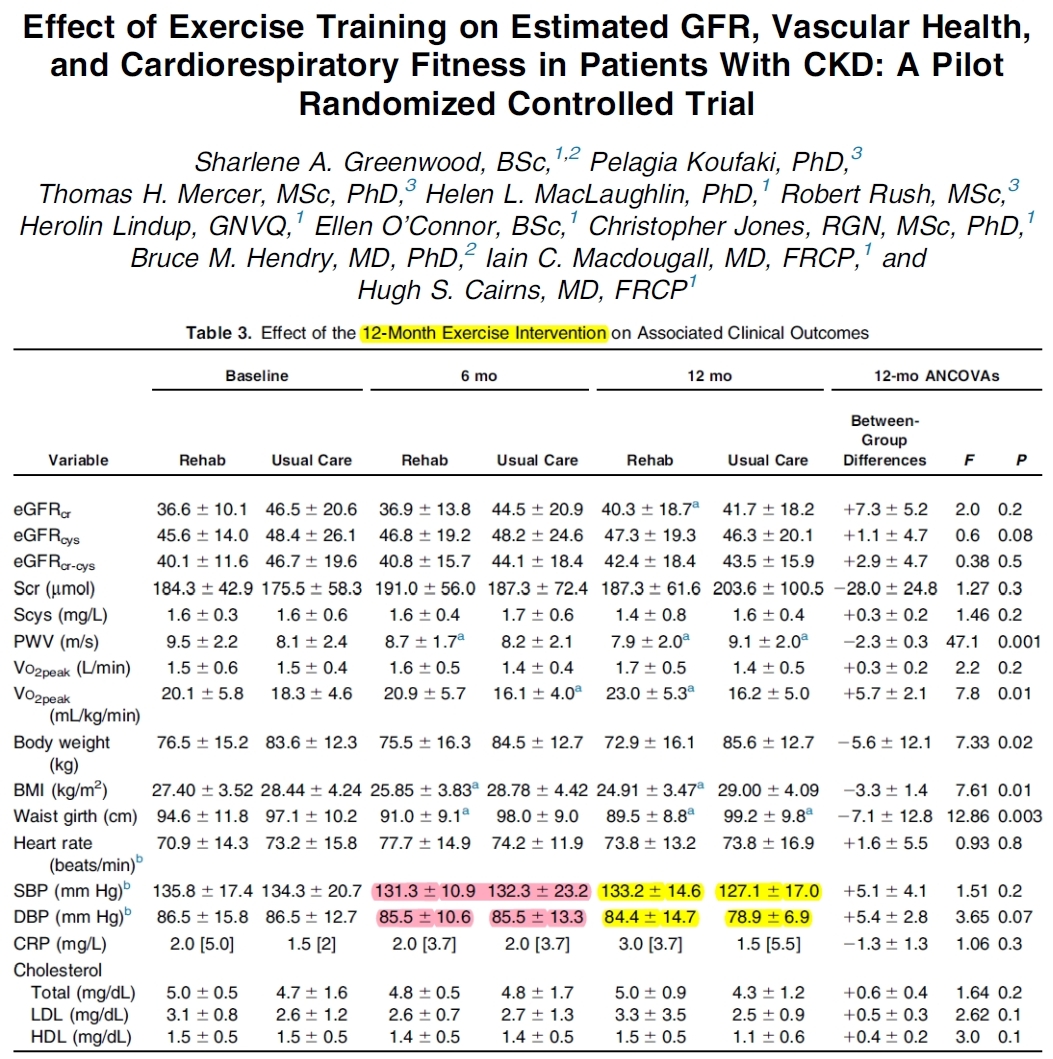

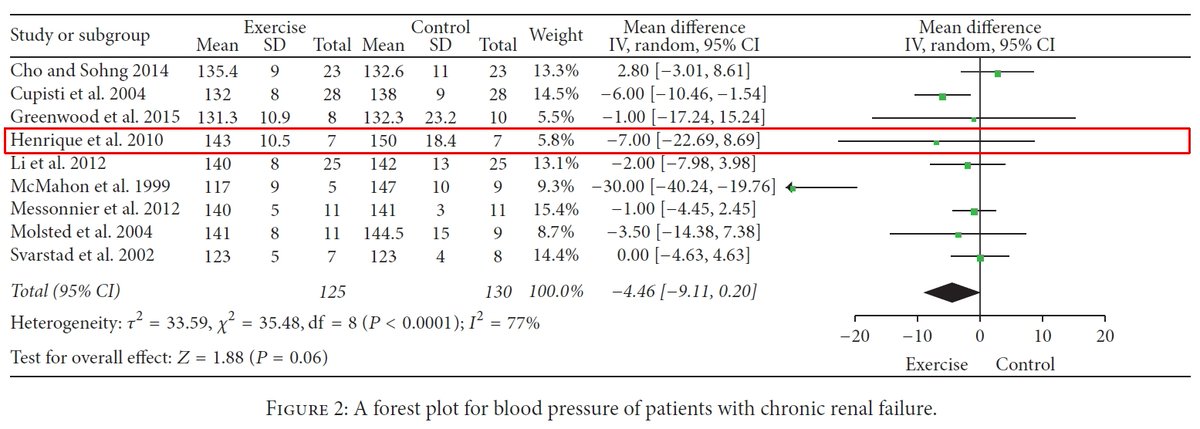

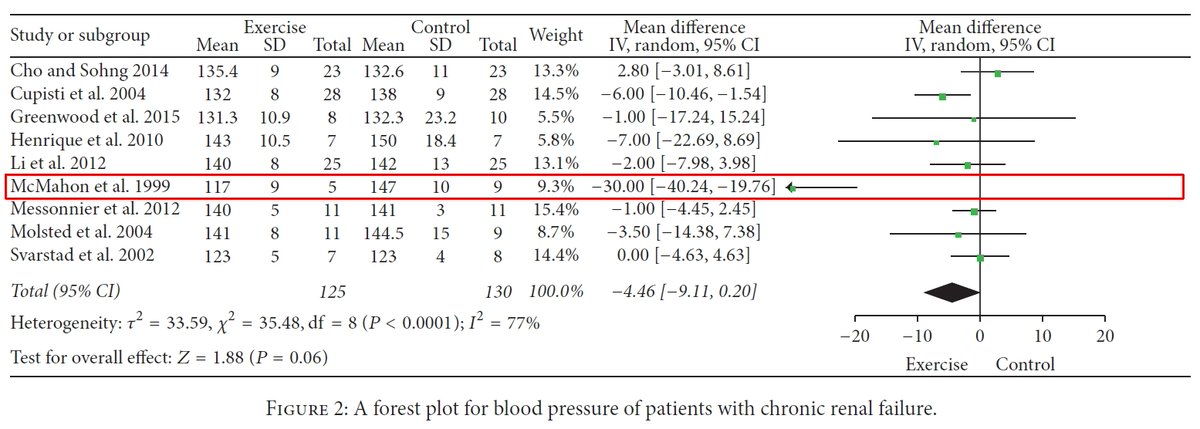

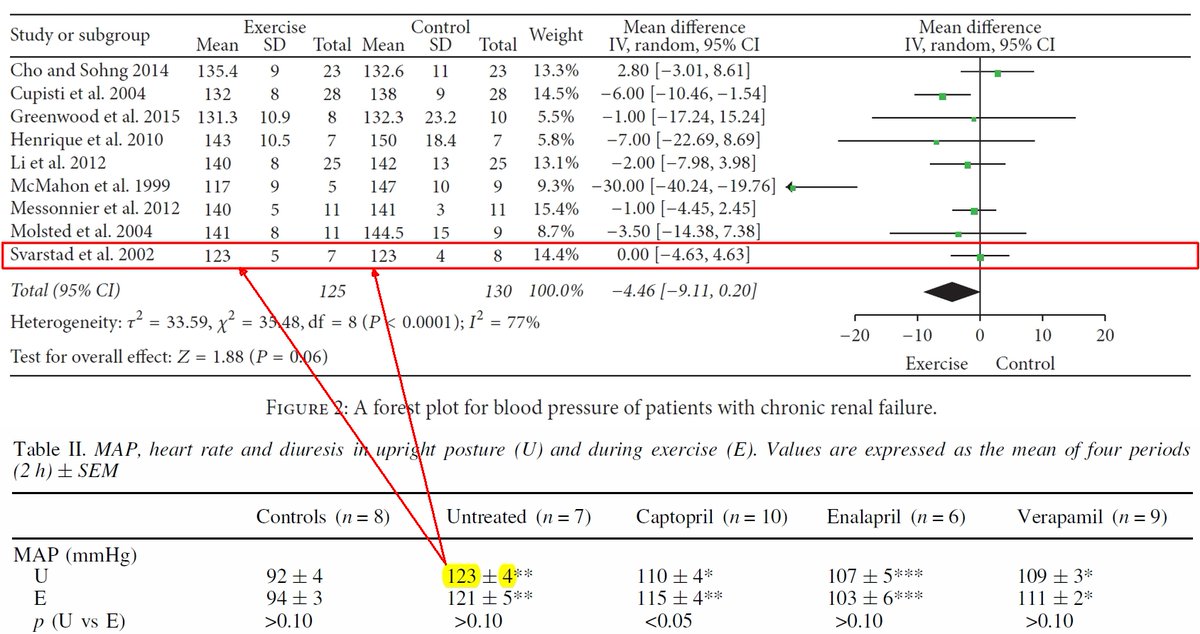

Supposedly, this was a meta-analysis of RCTs comparing exercise interventions to control. Well, let's see... We'll focus on just one of the several outcomes, namely blood pressure since it's so important for end-stage renal disease.

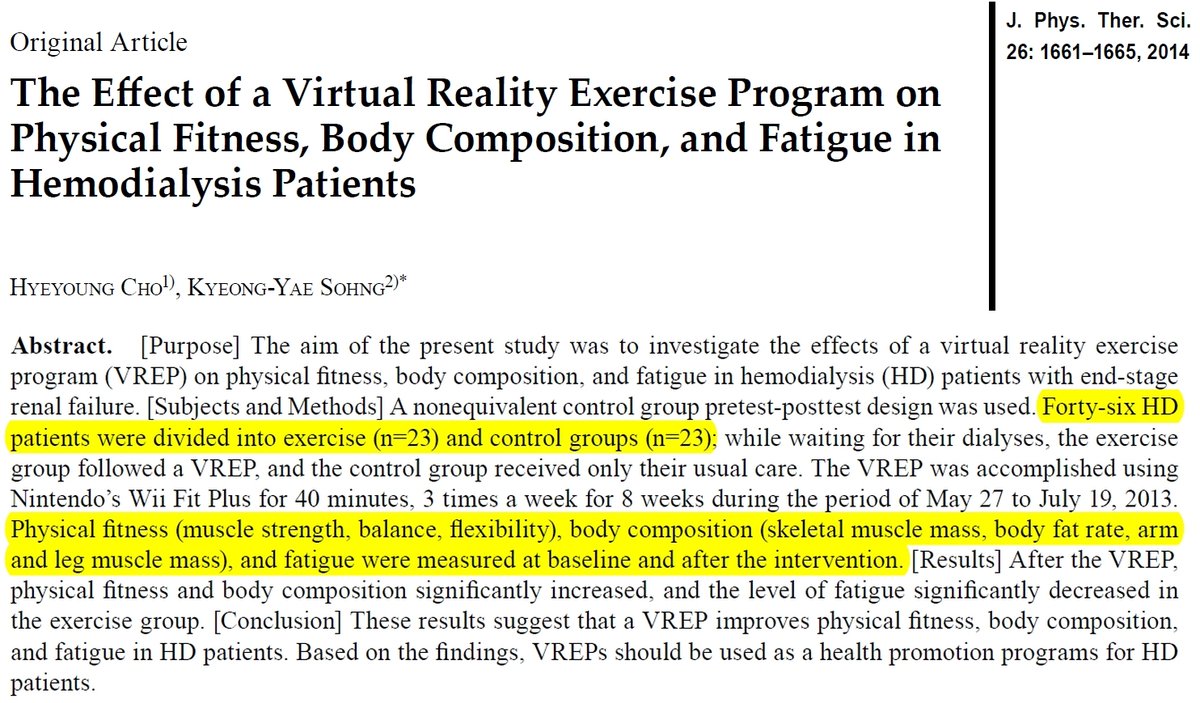

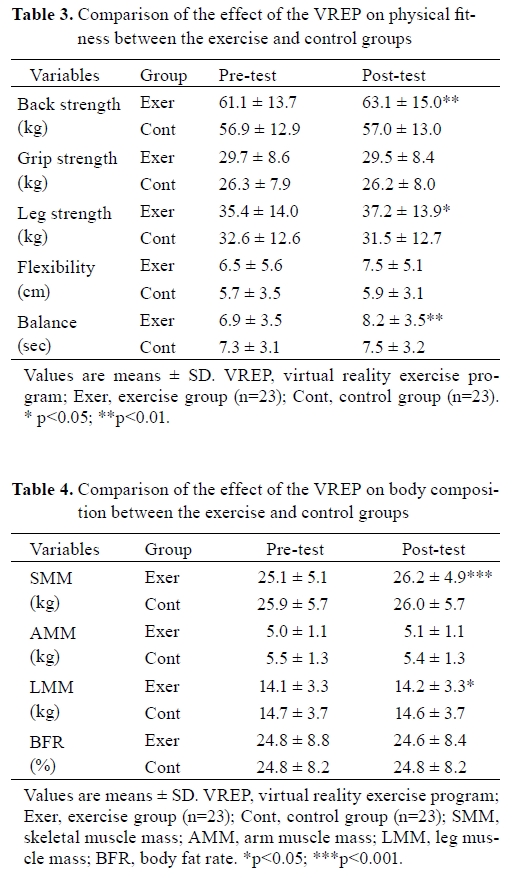

Cho and Sohng (2014) was not an RCT and it did not include an assessment of blood pressure (patients who received hemodialysis on Mon, Wed, Fri were the exercise group; those on Tue, Thu, Sat were the control group). The BP numbers in the meta are evidently made-up.

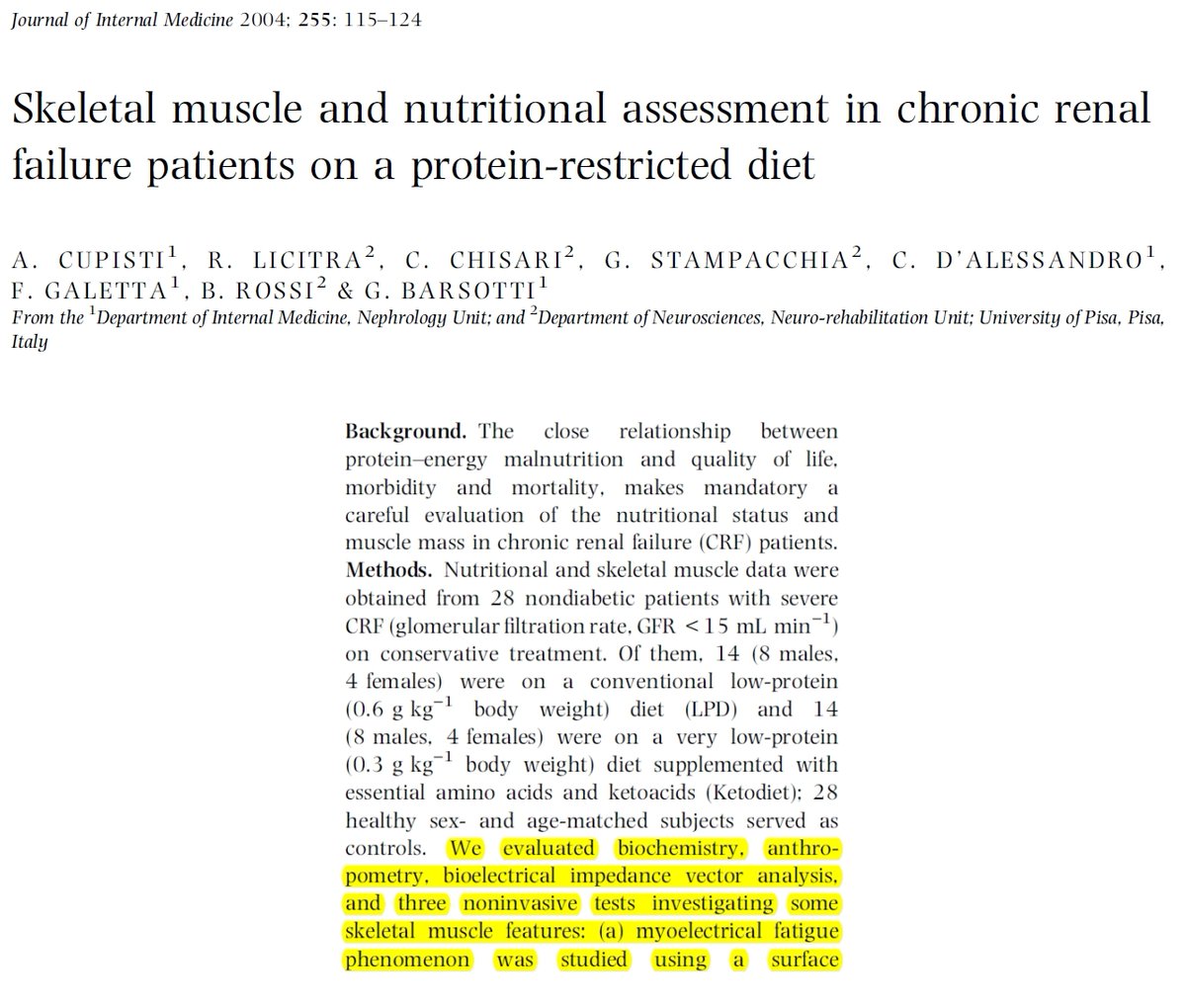

Cupisti et al. (2004) was not an RCT or an exercise intervention. It was a comparison between keto and low-protein diet. The BP numbers in the meta appear to be completely made-up.

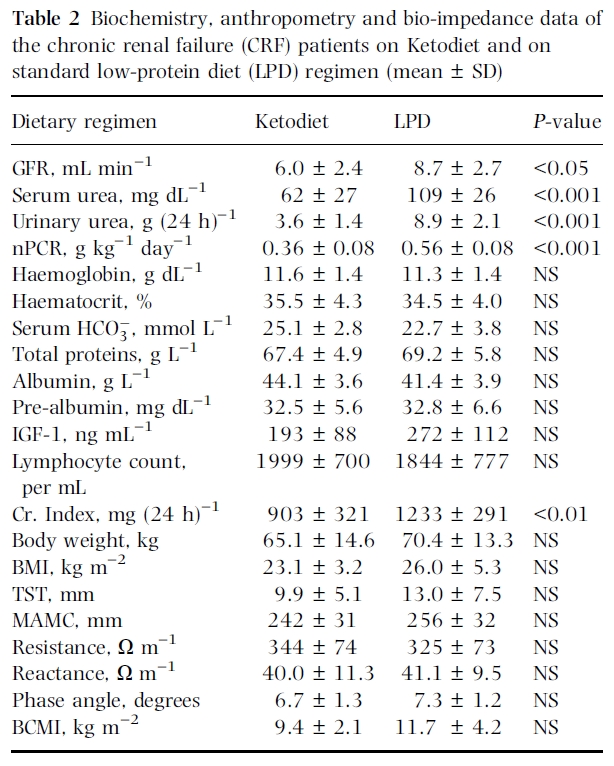

Greenwood et al. (2015) was an exercise RCT (yeah!) and they did assess blood pressure (double yeah!), though the meta-analysts, for some reason, entered the data from the middle of the intervention (6 months), not the end (12 months).

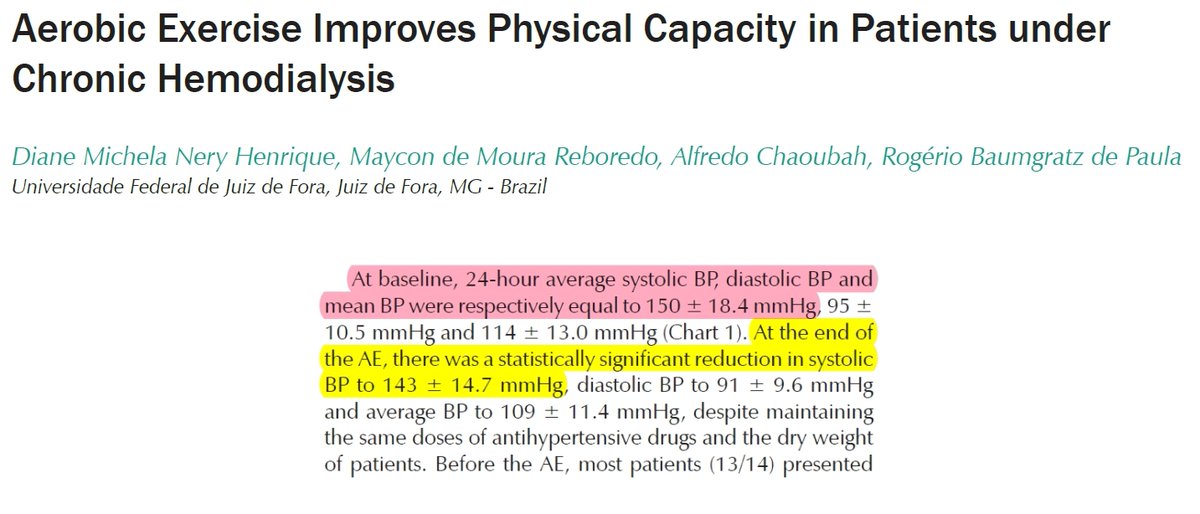

Henrique et al. (2010) was an uncontrolled intervention (single-sample). So, the meta-analysts used the baseline BP numbers as "control group" and divided the sample size (N = 14) by 2, saying that each "group" had 7 participants.

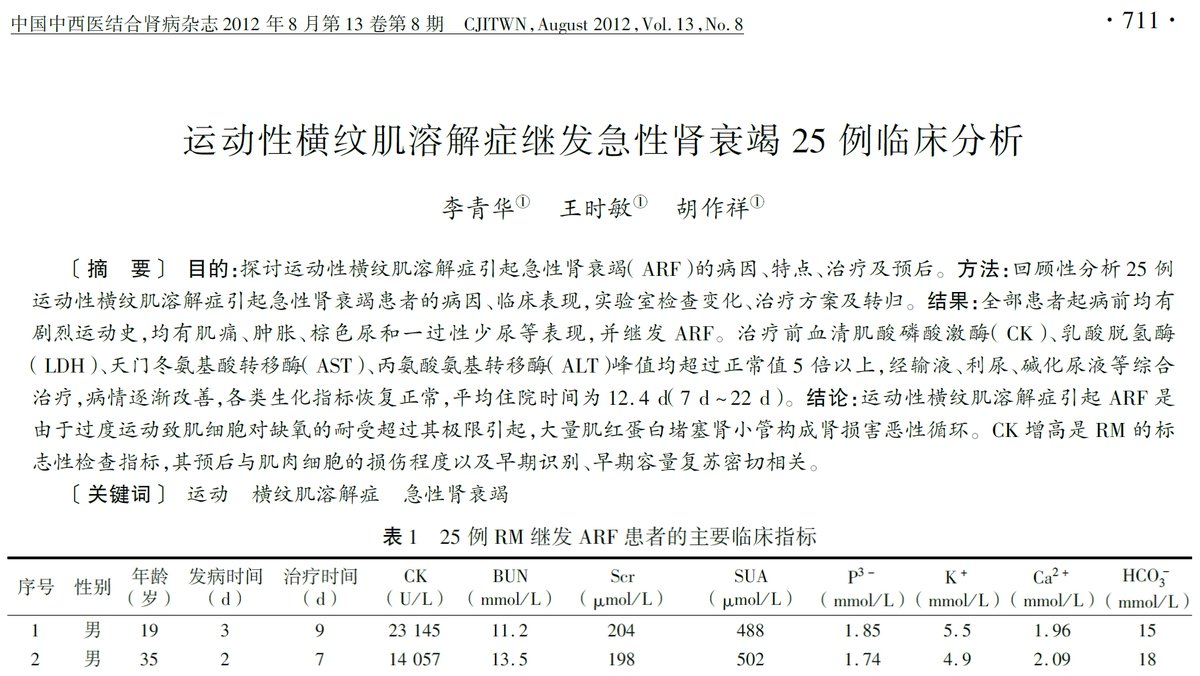

Li et al. (2012) was a Chinese study that was irrelevant to the topic (no exercise, not an RCT, no blood pressure). The numbers in the meta-analysis are entirely made-up.

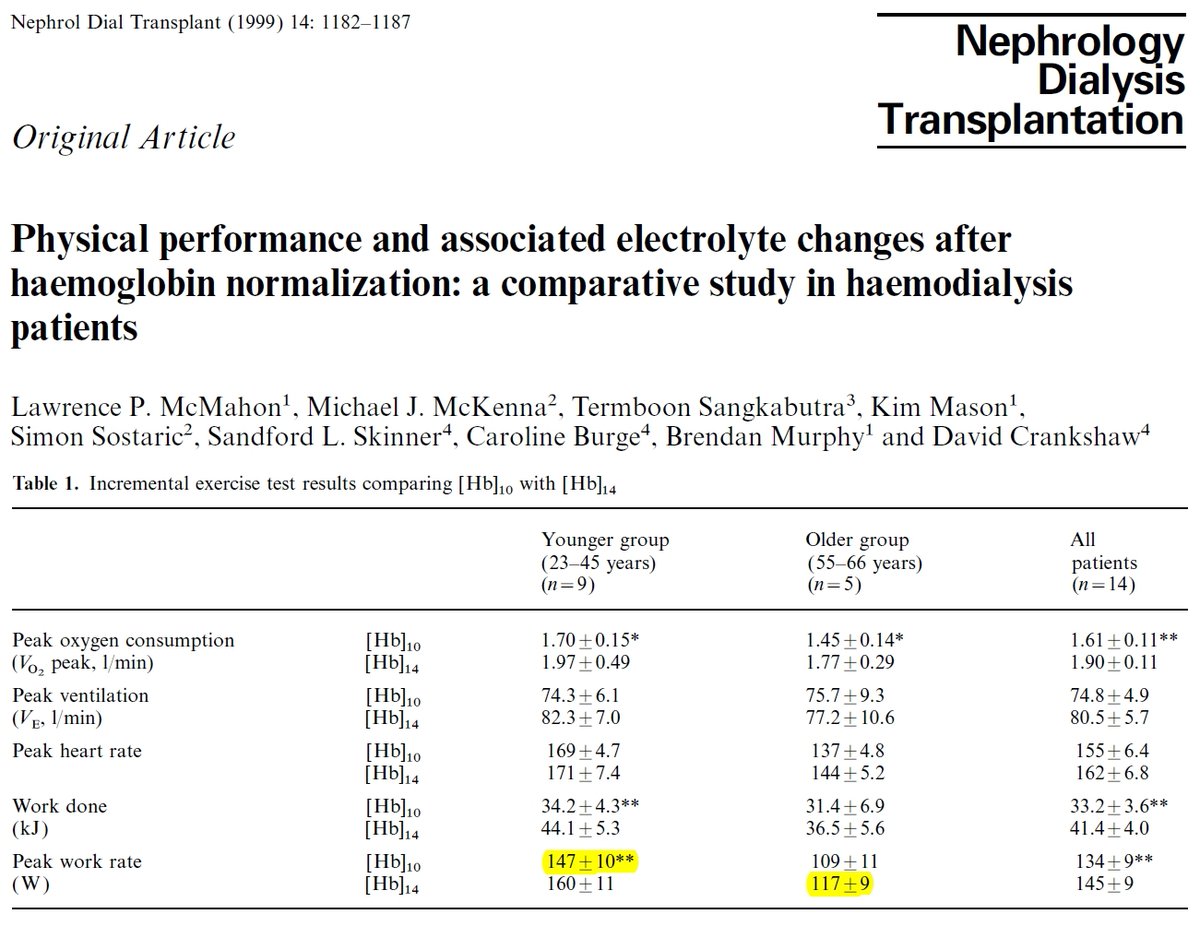

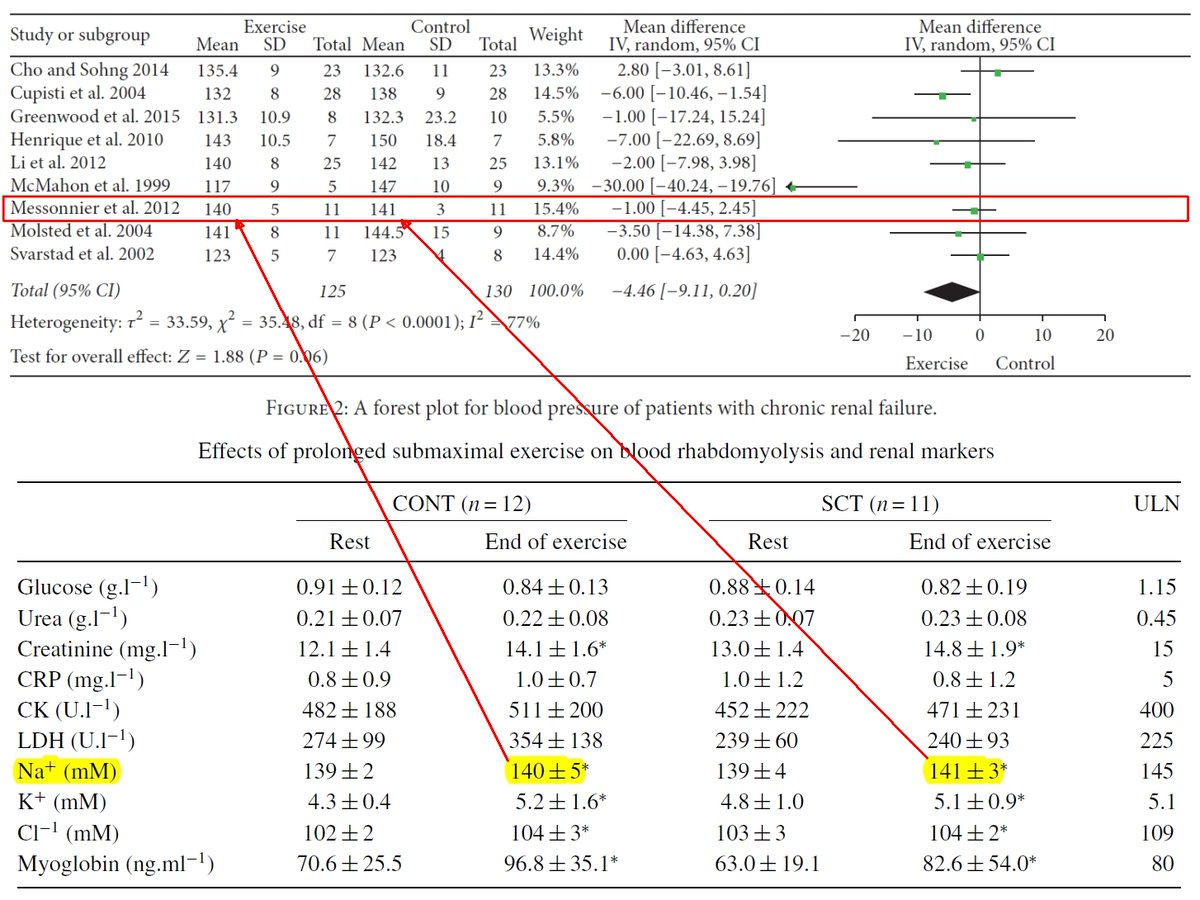

McMahon et al. (1999) examined responses to an exercise bout before and after hemoglobin normalization. The meta-analysts used the numbers for peak work rate (!!!) in the younger group before the intervention as "control" and the old group after the intervention as "exercise."

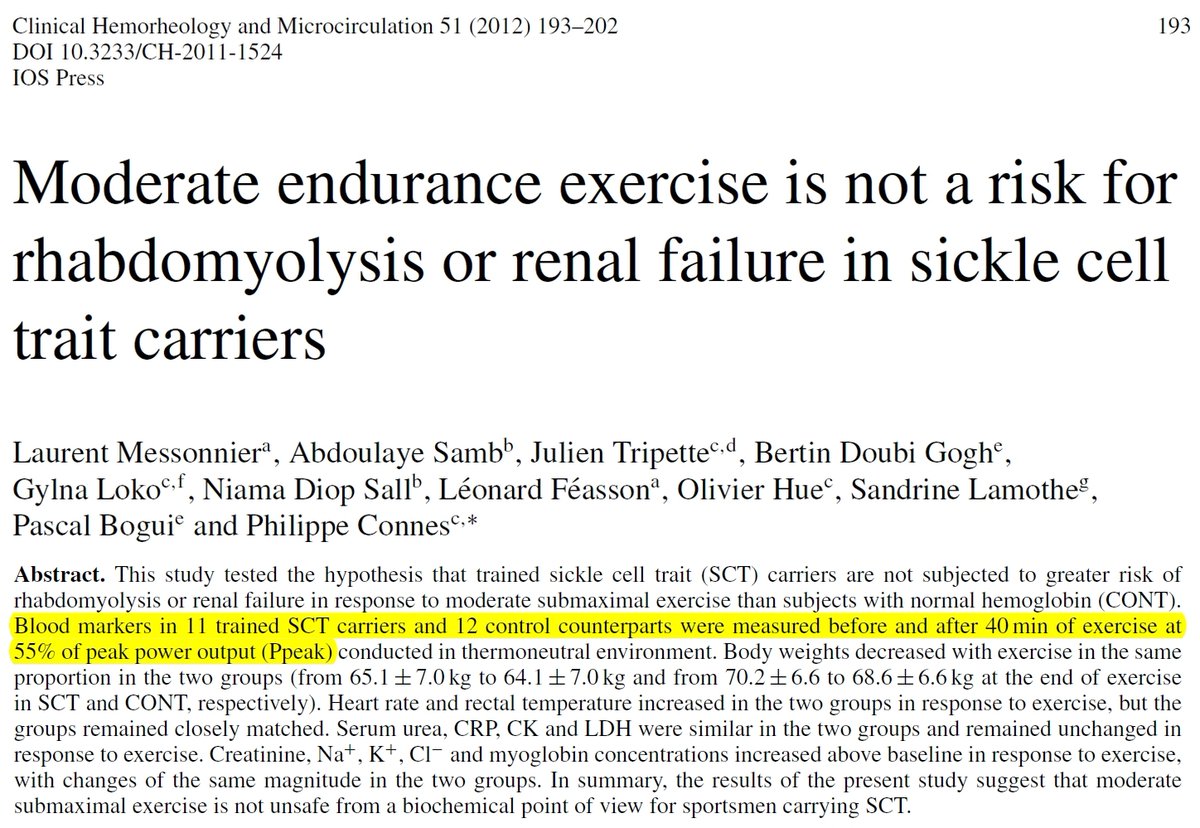

Messonnier et al. (2012) compared responses to a bout of exercise between sickle-cell patients & non-patients. There was no blood pressure, so the meta-analysts entered the data for Na+ at the end of exercise. The non-patients were "exercise" and the patients were the "control."

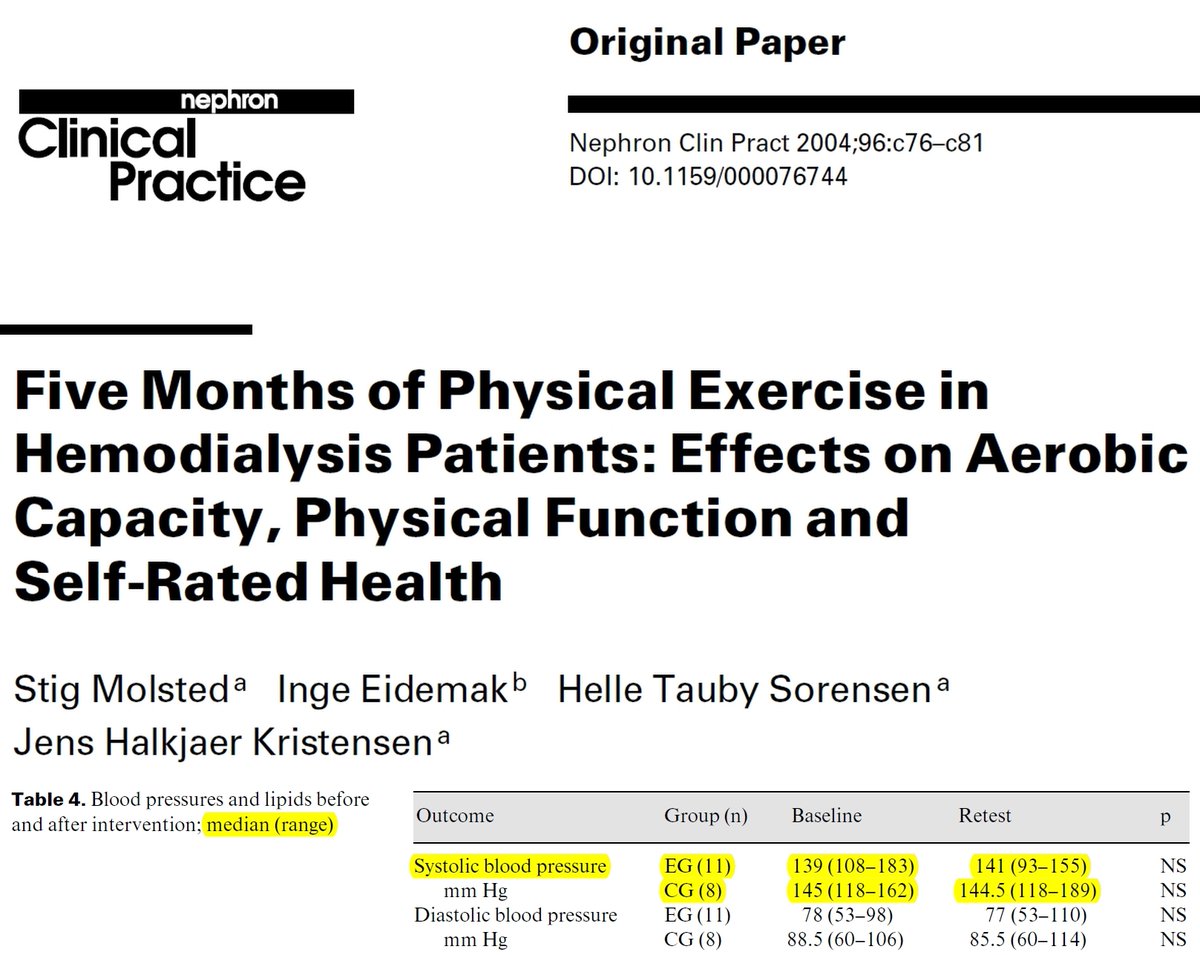

Molsted et al. (2004) was an exercise RCT (yeah!) but they reported blood pressure as median and range, so the meta-analysts entered the medians as means and seem to have made up the standard deviations.

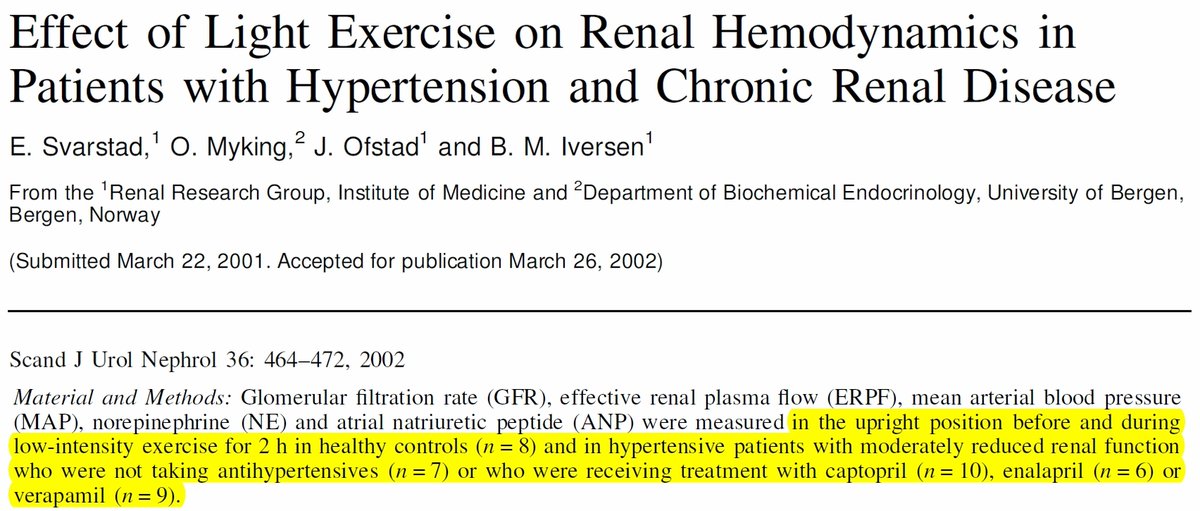

Svarstad et al. (2002) was not an exercise RCT. They compared responses of hypertensive patients before & during exercise, either untreated or treated with drugs (plus healthy controls). The meta-analysts used a number from patients before exercise as both "exercise" & "control."

I have not really seen anything like this. This is, at the same time, both hilarious in its ingenuity and absolutely tragic as an indication of the state of peer review in pay-to-play journals. The lesson is: never cite a meta-analysis blindly. Always make an effort to check!!!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh