In today’s #thread we are going to talk about the manufacturing process and use of black pigments in Roman mural paintings, with examples from @pompeii_sites and @MNR_museo. Let’s go!

Pliny and Vitruvius considered black (called atramentum) an artificial colour, because it required the transformation of raw materials. However, according to Pliny, it could also be found in salt-pits or sulfurous earths, and some painters used to dig up charred human bones.

Nonetheless, the most widespread manufacturing process was the calcination of pine resin in constructions that did not allow an escape for the smoke. The most esteemed black, according to Pliny, was prepared from the wood of Pinus mugo or Pinus cembra.

https://twitter.com/moonikoffice/status/1322633780058750977

According to Vitruvius, manufactories consisted of a furnace with vents opened into a laconicum, finished in polished marble. When the resin was burnt, the soot was forced through the vents and sticked to the walls and the vaulting of the laconicum.

https://twitter.com/Roman_Britain/status/1213412899445788672

This pigment was usually adulterated with ordinary soot from furnaces and baths, the same that was used mixed with gum to write graffiti on the walls.

https://twitter.com/pompei79/status/1297824183473364992

When this type of constructions were not available, shavings and splinters of pitch pine were burnt and pound in a mortar with size.

On the other hand, wine-lees could also be calcined. The better the original wine, the finer the final pigment, even equivalent to Indicum black, brought from India. Polygnotus and Micon used this black pigment and called it “tryginon”.

https://twitter.com/StoneHouse_Vine/status/1232400910921457665

Speaking about wine, just take a moment to appreciate this #thread on wine production in @pompeii_sites.

https://twitter.com/pompeii_sites/status/1322144748065460229

Apelles, another celebrated Athens painter, created his own method to obtain a black pigment from charred ivory and called it, consequently, “elephantinon”.

https://twitter.com/greenandstone/status/1200730412919742465

It is also well known that Greek painters appreciated atramentum, since it was one of the four colours employed by the most illustrious ancient painters, next to melinum for the white, Attic sil for the yellow and Pontic sinopis for the red.

https://twitter.com/mv_arte/status/1141758852704231425

Both Pliny and Vitruvius commented that atramentum could not be directly applied on fresco paintings, but that it should be mixed with size beforehand, probably to counteract the oily nature of the black, which would cause it to shed water.

https://twitter.com/Oskar_KimikArte/status/1115150537219919872

There are numerous examples of widespread use of atramentum as black background in mural paintings from @pompeii_sites, including room M and the peristyle of the House of the Golden Cupids (Regio VI, 16, 7).

Another luxurious and fascinating example of the use of a black background in mural paintings is the Imperial villa of Boscotrecase, shared by @DrJEBall.

https://twitter.com/DrJEBall/status/1296776852103729153

We could not forget to mention this superb black background of the winter triclinium of the Villa della Farnesina, conserved at @MNR_museo and shared by @DariusAryaDigs.

https://twitter.com/DariusAryaDigs/status/1304298475887251457

Heading back to @pompeii_sites and Torre Annunziata, let’s take a minute to cherish these delightful animal depictions on a black background of Villa de Contrada Bottaro, shared by @DrJEBall.

https://twitter.com/DrJEBall/status/1286576068753793024

Regarding the analysis of Pompeian pigments recovered at @pompeii_sites, samples 9398 and 18128 have revealed a mixture of silicates and tenorite (black copper oxide) and vegetal charcoal (with partially charred fibers), respectively.

tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108…

tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108…

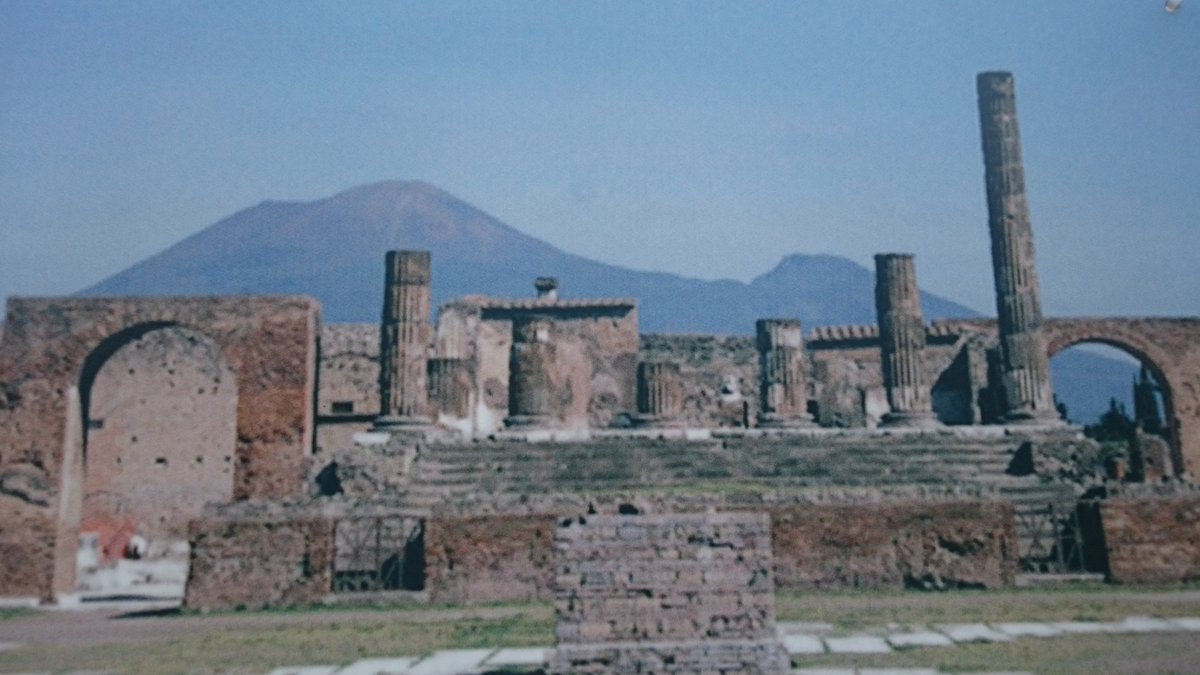

Tenorite has also been identified in grey pigments of @pompeii_sites. This mineral is present in volcanic fumaroles and was described for the first time in the 19th century in Mt. Vesuvius. Hence, its local availability could favour its use as a pigment.

https://twitter.com/NadWGab/status/1010590814219616256

However, tenorite is mixed in these samples with #EgyptianBlue (CuCaSi4O10), which is also naturally found in Mt. Vesuvius. Thus, the mixture could be due to an impurity or to the occurrence of black tenorite in the manufacturing process of #EgyptianBlue.

https://twitter.com/cinnabarim/status/1276906057223331840

In the Temple of Venus at @pompeii_sites, many of the pigments were confirmed to be carbon black, obtained charring vegetal species and not bones, as Pliny mentioned, since phosphorus, an element related to the apatite of the bones, has not been detected.

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

Finally, it is worth mentioning that one of the pigments employed at the Temple of Venus was not a genuine carbon black, but iron oxides calcined at a low temperature to obtain a very dark hue.

This brings us to the last tweet of this #thread: not everything that is black now at @pompeii_sites used to be that black. As we have already explained, red cinnabar suffers a blackening process that leads to a misperception of the original colour.

https://twitter.com/cinnabarim/status/1260998135956062209

Aquí te cuento este #hilo en castellano:

https://twitter.com/cinnabarim/status/1322951618732740613?s=19

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh