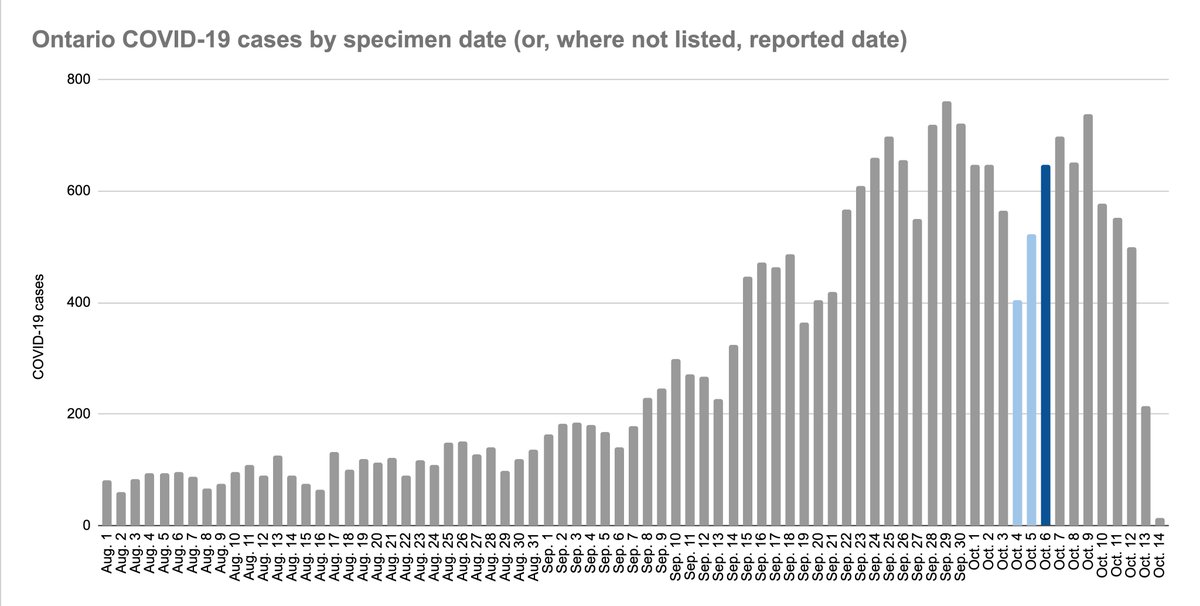

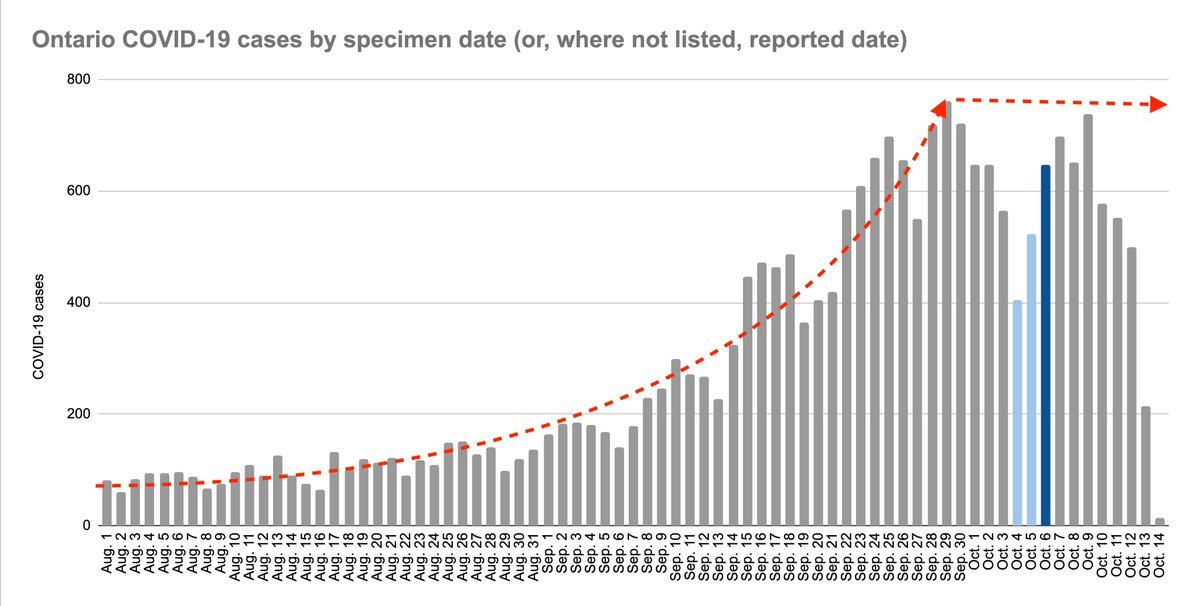

1/n Not long after I did the attached chart of cases by age, I realized I could use the Ontario database to predict how deadly each day's set of new cases might be, based on the age breakdown and their average death rates.

That's easy enough.

That's easy enough.

https://twitter.com/EdTubb/status/1321126277898711046

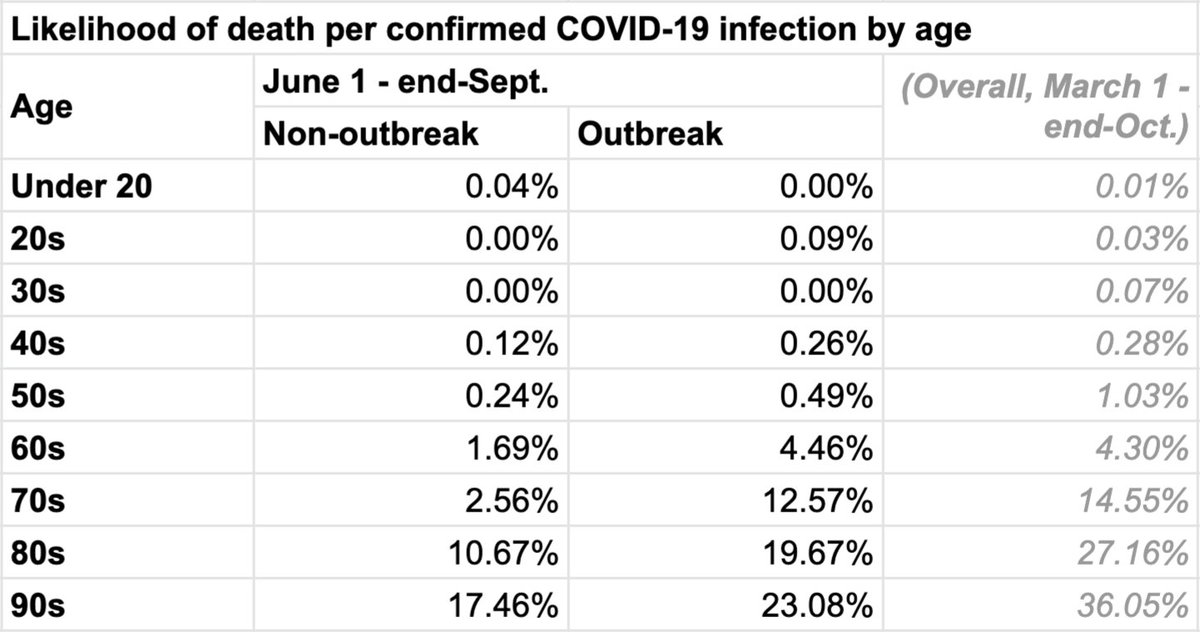

2/n First, we know two important things about the COVID-19 death rate.

1. It's become a lot lower over time, probably because we're better prepared to treat it.

2. It takes some time for some patients to die.

1. It's become a lot lower over time, probably because we're better prepared to treat it.

2. It takes some time for some patients to die.

3/n If you're looking to estimate how likely any given patient is to die, it's simple enough to resolve those issues.

1. Throw out data from the spring.

2. Throw out recently infected cases, and any case listed "not resolved".

1. Throw out data from the spring.

2. Throw out recently infected cases, and any case listed "not resolved".

4/n Another important thing to note is that some folks are especially vulnerable to COVID-19, people in nursing homes, especially.

Thankfully, the Ontario database tells you if someone caught the virus in an outbreak — and that's a pretty good proxy for those nursing home cases.

Thankfully, the Ontario database tells you if someone caught the virus in an outbreak — and that's a pretty good proxy for those nursing home cases.

5/n So: We have a method.

Take the age distribution and outbreak status of each day's cases, and run that against the average chance of death for similar cases reported June thru end-Sept.

For Ontario, that looks like this:

Take the age distribution and outbreak status of each day's cases, and run that against the average chance of death for similar cases reported June thru end-Sept.

For Ontario, that looks like this:

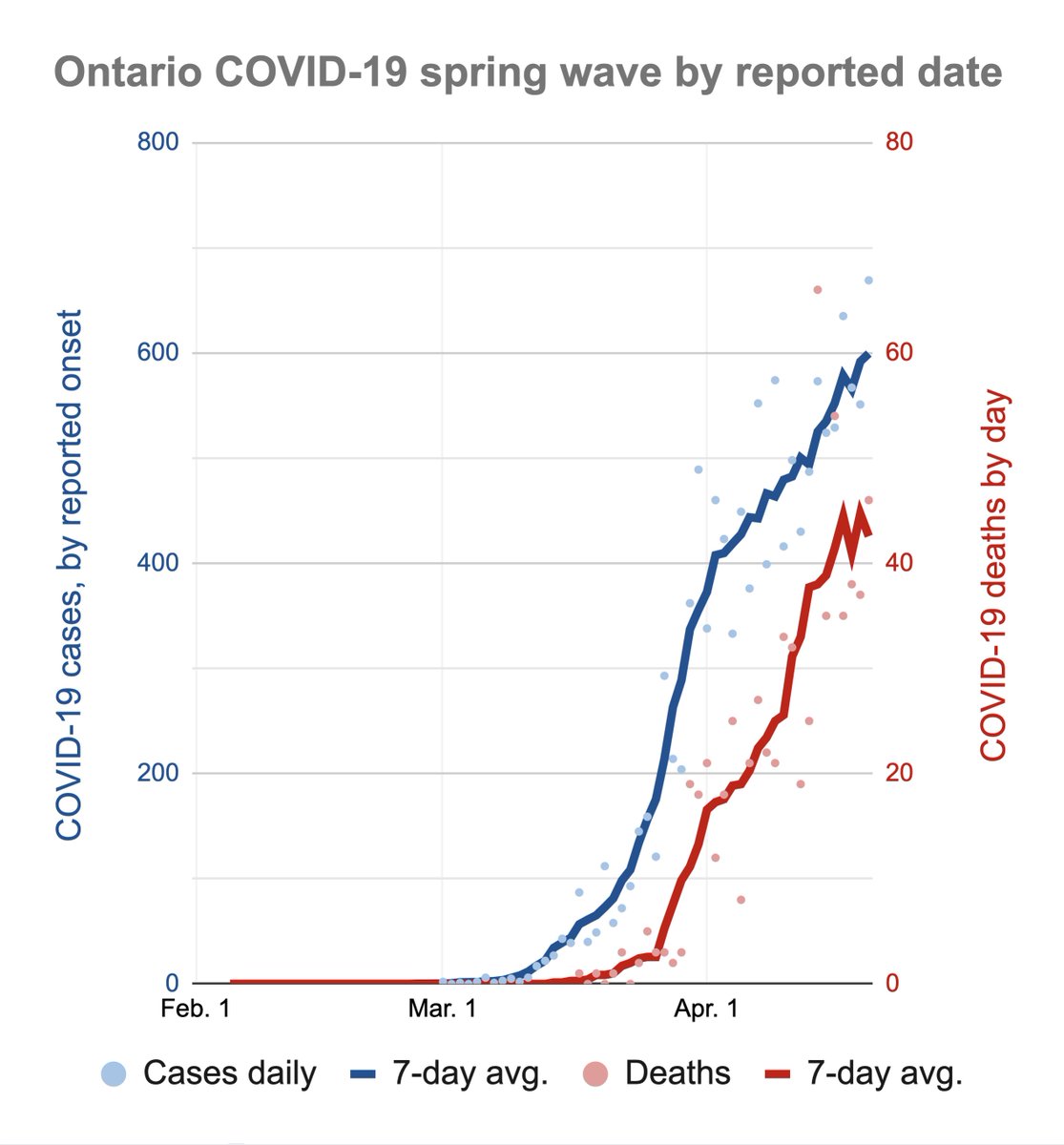

6/n Clearly, 1. age is the primary factor in whether any given patient dies, and 2. Ontario's was much better at treating the average patient over the summer than in the spring.

OK. Now it's just a matter of taking each day's set of cases, and using these averages.

OK. Now it's just a matter of taking each day's set of cases, and using these averages.

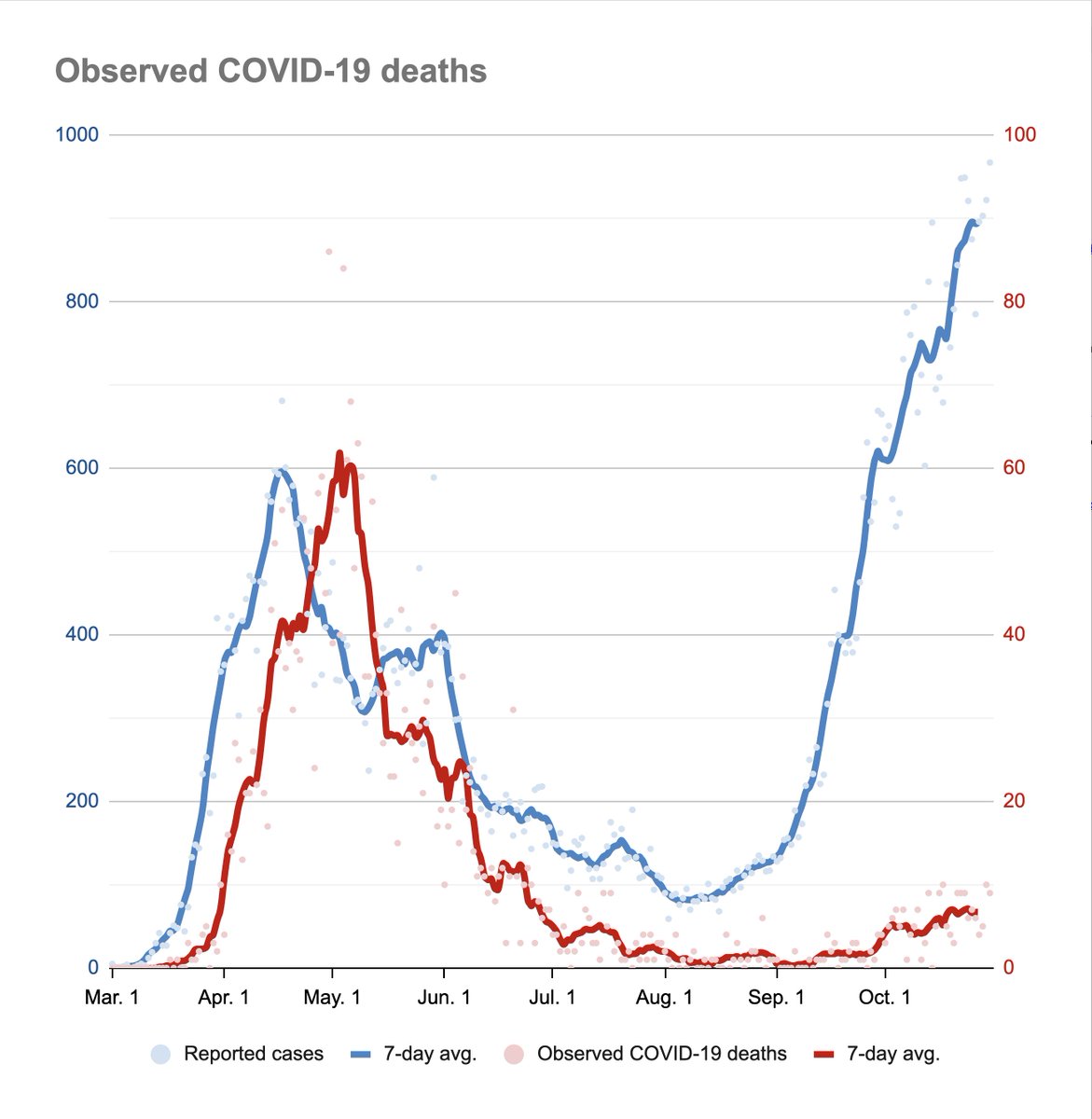

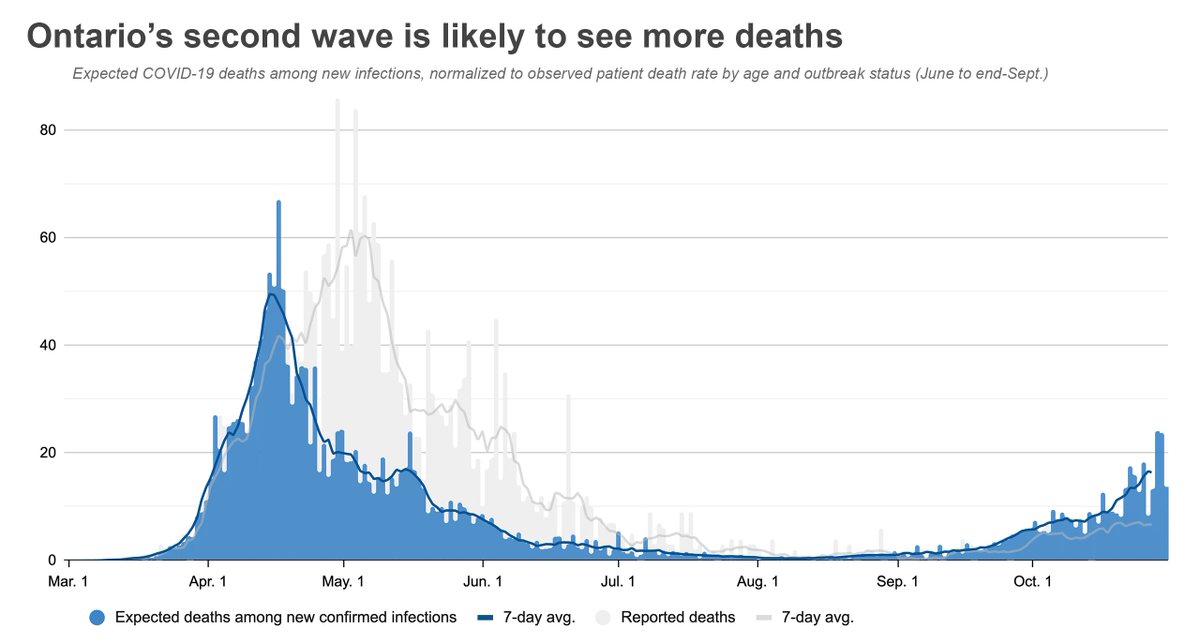

7/n And here you have it, Ontario's COVID-19 pandemic by a single metric of "expected deaths."

Basically, based on the age and outbreak status of the folks who got sick in Ontario today, this is the number you'd expect to die, based on the rates we saw over the summer.

Basically, based on the age and outbreak status of the folks who got sick in Ontario today, this is the number you'd expect to die, based on the rates we saw over the summer.

8/n The *other* thing you achieve by normalizing to the averages over the summer is you now have the ability to directly compare wave 1 with wave 2.

(Add this to my endless list of tweets on why deaths aren't yet spiking in Ontario's fall wave).

(Add this to my endless list of tweets on why deaths aren't yet spiking in Ontario's fall wave).

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh