THREAD: The parable of the Lost Sheep, and punctuation.

I've been struggling with Jesus's story of the Lost Sheep (Luke 15:3-6 // Matthew 18:12-14).

In both gospels it's set in the form of a question.

In ESV/THGNT/NA28 Matthew 18:12 has 2 questions & 18:13-14 are statement.

I've been struggling with Jesus's story of the Lost Sheep (Luke 15:3-6 // Matthew 18:12-14).

In both gospels it's set in the form of a question.

In ESV/THGNT/NA28 Matthew 18:12 has 2 questions & 18:13-14 are statement.

These versions have Luke 15:4 as question & 15:5-7 as statement.

I've been struggling to understand the question 'What man of you, having a hundred sheep and losing one of them does not leave the ninety-nine in the wilderness and go after the lost until he find it? (Luke 15:4)

I've been struggling to understand the question 'What man of you, having a hundred sheep and losing one of them does not leave the ninety-nine in the wilderness and go after the lost until he find it? (Luke 15:4)

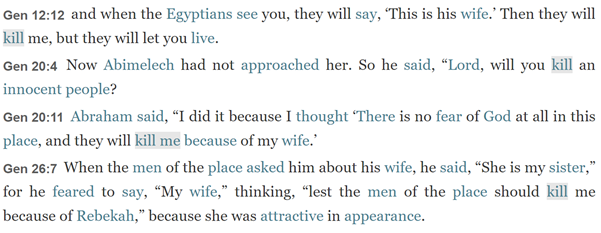

Do we follow Kenneth Bailey's view that, of course, no flock would be left alone, and that the audience would have understood that the 99 were left with someone else (Finding the Lost, pp. 72-73)?

Is Jesus presenting bizarre behaviour as normal, or normal behaviour as normal?

Commentators differ.

Then I realised I was being thrown off by the question mark.

These beautiful little terrors weren't even invented before the 5th century.

cam.ac.uk/research/news/….

Commentators differ.

Then I realised I was being thrown off by the question mark.

These beautiful little terrors weren't even invented before the 5th century.

cam.ac.uk/research/news/….

You can see a nice question mark at the end of 15:4 in the 1537 Matthew's Bible (6 lines from bottom), before the shepherd goes to gather his 'lovers' (3 lines from bottom)😏

The question mark can be traced earlier. Here's a Middle English case of the question mark just at this point. I love this sort of walking man on top of a sort of 7 in the Wycliffite version (Corpus Christi Manuscript 440), 'til he fynde it?'

But the punctuated Greek manuscripts I consulted (ms 017 beautiful caps, 9th century; ms 1424 with commentary to right, 10th century; ms 69 dead ugly, 15th century) do not have any special sign for a question mark here.

And the beautiful #BookofKells (9th century) in Latin gets away with no punctuation at all till the end of the paragraph.

Only after reflection did I come to realise how pernicious question marks are in biblical interpretation (they're harmless in many other contexts). They dichotomize questions and statements and force us to say that Jesus's question has stopped before it actually has.

Here they force us to say that Jesus's question has stopped at 15:4, and leave me wondering whether the behaviour of the shepherd is weird or not.

But grammatically all of 15:4-6 can flow as a single enquiry:

'Who doesn't get this excited when they find a lost sheep?'

But grammatically all of 15:4-6 can flow as a single enquiry:

'Who doesn't get this excited when they find a lost sheep?'

The oddness of Jesus's query is best experienced in relation to the whole, not just the single part of whether the shepherd leaves the sheep alone.

You see, our question marks are question termination marks. They presuppose that a question has a clear end.

You see, our question marks are question termination marks. They presuppose that a question has a clear end.

I'm running a campaign for typographical reform of Bibles.

With #THGNT I hope to encourage modern translations to use NT manuscripts for paragraphs.

We simplified punctuation, but maybe question marks should go too. After all, Hebrew OT's have survived for longer without them.

With #THGNT I hope to encourage modern translations to use NT manuscripts for paragraphs.

We simplified punctuation, but maybe question marks should go too. After all, Hebrew OT's have survived for longer without them.

I also have an article forthcoming (sorry I can't say where for now) on the evils caused by quotation marks in Bibles.

Not only might such reading 'aids' be put in the wrong place, but often their very presence leads us to anachronistic reading habits.

Not only might such reading 'aids' be put in the wrong place, but often their very presence leads us to anachronistic reading habits.

The moral of the sheep's tail:

Don't let question marks lead you astray.

Don't let question marks lead you astray.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh