In light of the discovery of the two bodies at the villa at Civita Giuliana, we look at the process involved in excavating, recording & casting them.

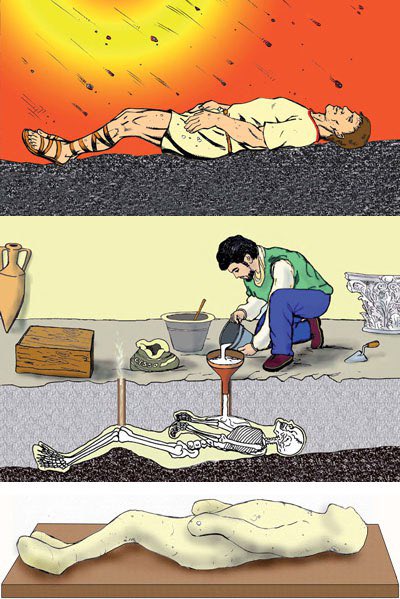

Volcanic ash from the eruption compacted & hardened around everything it covered. It’s in this layer of ash that voids are found.

Volcanic ash from the eruption compacted & hardened around everything it covered. It’s in this layer of ash that voids are found.

Scraping the surface of the ash reveals a small hole indicating a void is beneath.

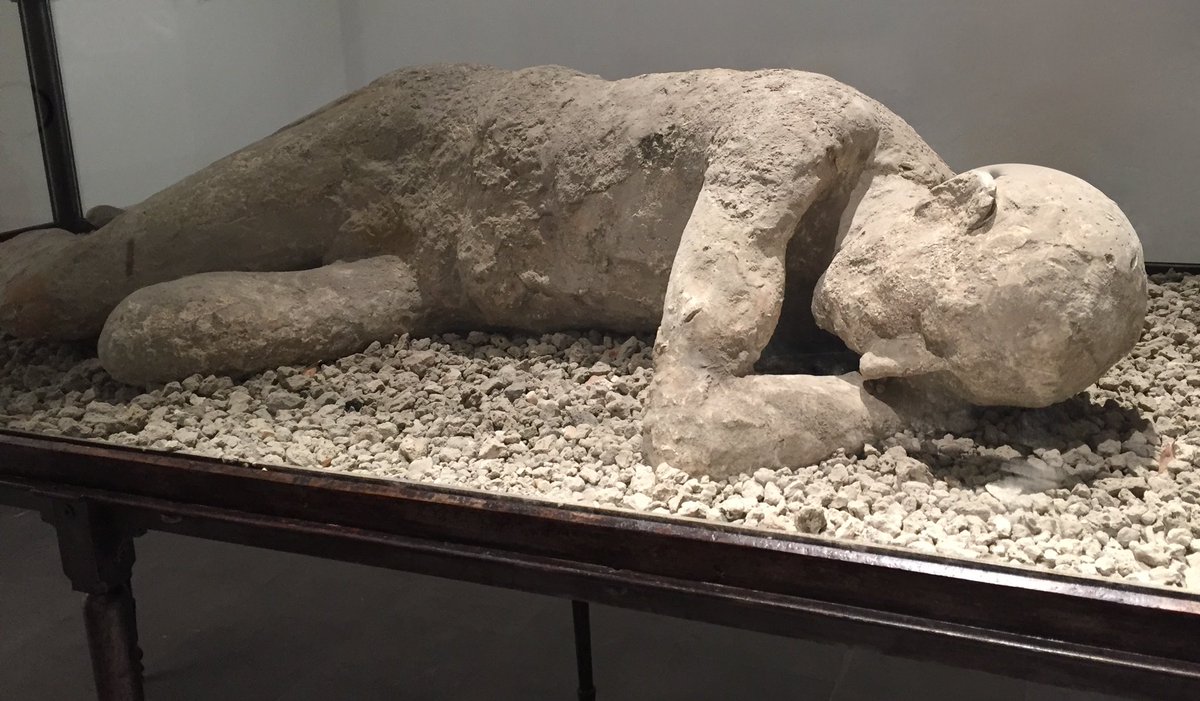

The voids are created in the ash as organic material decomposes over time leaving a complete mould in the form of what was once inside: in this case the forms of 2 humans lying in supine positions.

The voids are created in the ash as organic material decomposes over time leaving a complete mould in the form of what was once inside: in this case the forms of 2 humans lying in supine positions.

Advances in technology now allow for the exploration and documentation of the cavity before it is cast. Endoscopic analysis permitted the gathering of information and recorded the position of the bones and a 3D scan of the void was made.

The hole in the ash was slightly enlargened to retrieve samples of the bones so that analysis can be made on them in order to determine facets of these people’s lives such as sex, age and health of the victim. The skull is usually too fragile to remove and so remains in the cast.

A plaster solution is then carefully poured into the cavity, usually through a few entry points, until the void is full. The plaster is allowed to dry & set before the ash encasing it is scraped away to reveal the form of the cast including details like the folds in the textiles.

One cast is in a ‘pugilistic pose’. In intense heat (in this case the pyroclastic surge) the muscles of individuals contract and the limbs flex producing the stance similar to that of a boxer in a defensive position. Testimony to the horror of the moment of his death.

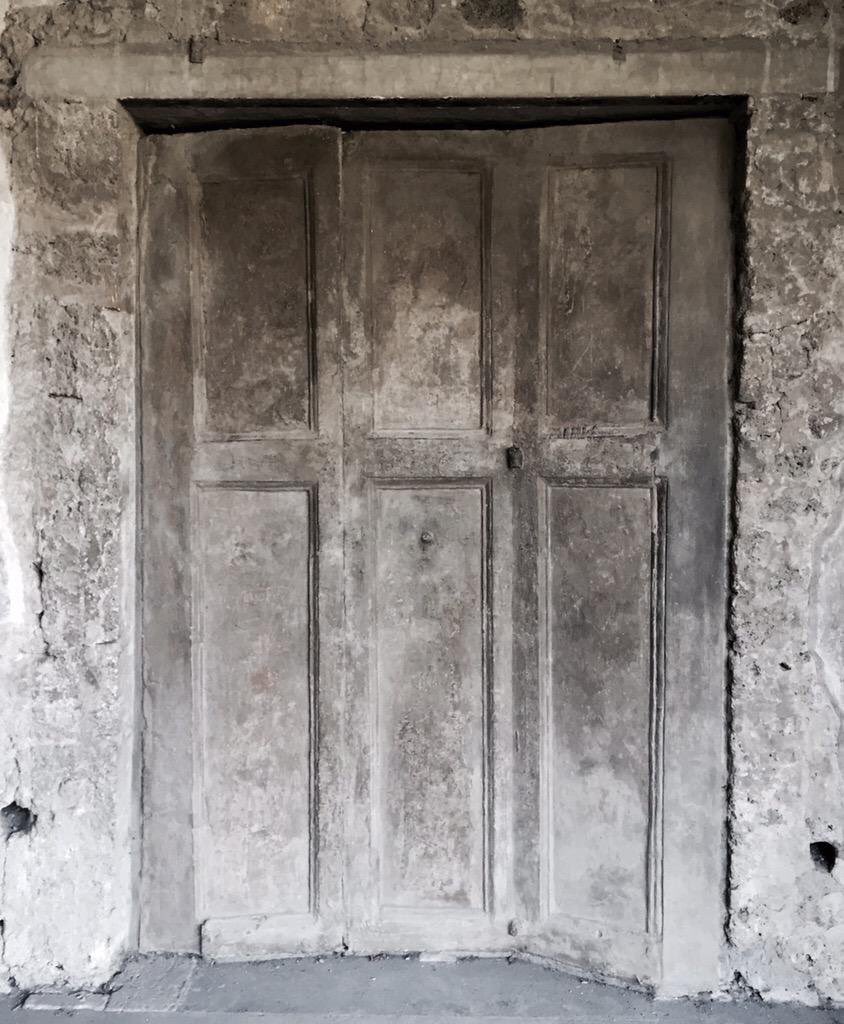

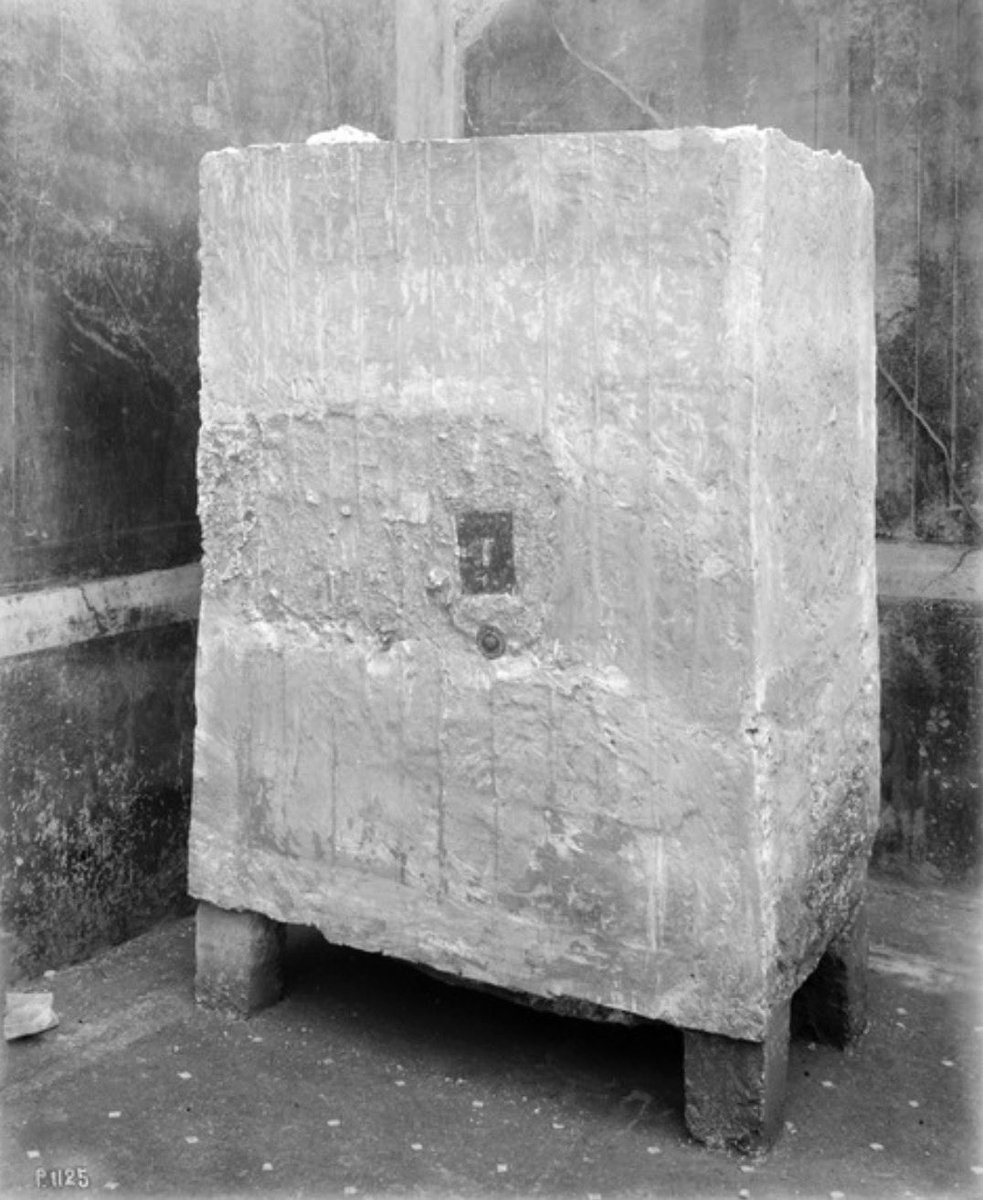

This method of casting voids is not new & nor is it limited to human cavities. In 1856 Spinelli, director of Pompeii made the first cast of a wooden door. Wood, being organic material, decayed & left a void in the ash deposit. Other wooden objects & furniture have also been cast.

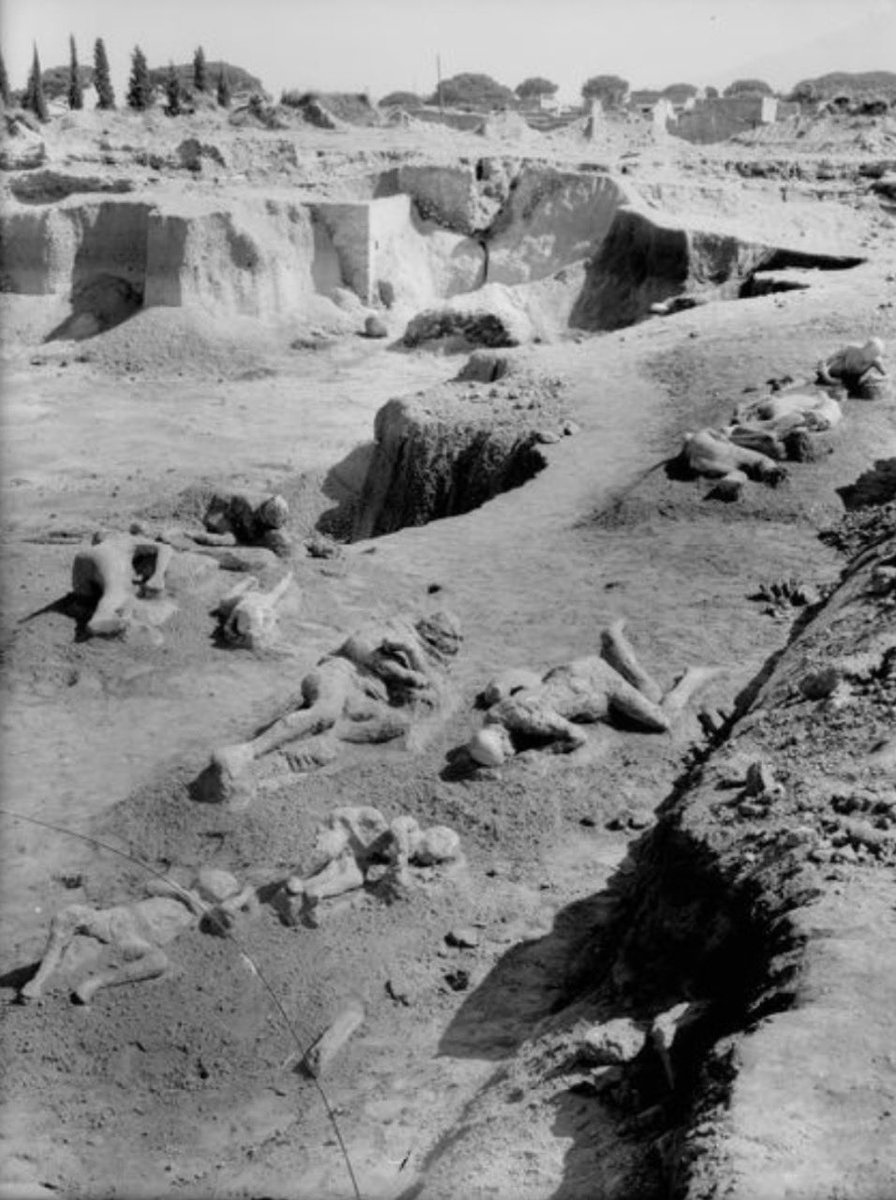

On 3rd February 1863 director of excavations, Giuseppe Fiorelli made the first plaster cast of a human found in a street, now the Vicolo degli Scheletri, lying in the ash 4m above street level. Where possible, casts are left where they’re found as in the House of Fabius Rufus.

Casts of animals have been made. The most famous and heart-wrenching being the dog from the House of Vesonius Primus found tethered by a chain so could not escape. There is also the cast of a pig from Boscoreale & most recently, a complete horse from the villa at Civita Giuliana.

The most recent adaptation of the casting technique was by Wilhelmina Jashemski in her research on the gardens of Pompeii. She cast the root cavities of plants & trees and by studying the shape of the cast she identified the species of flora & reconstruct the vegetation present.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh