For the last 4 months @Niksteffens @ReicherStephen @sarahvivbentley & I have been working on a major review of leadership during #COVID19. It was accepted for publication in Social Issues & Policy Review today and a preprint can be accessed here: psyarxiv.com/bhj49/

1/n

1/n

The review was built around a 5R model of *identity leadership* and abstracted 12 key lessons. Some of these (e.g., Lesson 10) may seem obvious, but they challenge dominant models of leadership and crisis management a range of ways.

2/

2/

1. Focus on achieving power through people not power over them

The paternalistic imposition of power is the antithesis of leadership because it alienates people and casts them as opponents rather than allies. As a result, it dampens enthusiasm and fuels resistance.

3/

The paternalistic imposition of power is the antithesis of leadership because it alienates people and casts them as opponents rather than allies. As a result, it dampens enthusiasm and fuels resistance.

3/

2. Recognise groups as the solution not the problem.

Much received psychology casts groups and their psychology as a source of problems. But while it is important to avoid #groupthink (by establishing critical group norms), leaders must still think group.

4/n

Much received psychology casts groups and their psychology as a source of problems. But while it is important to avoid #groupthink (by establishing critical group norms), leaders must still think group.

4/n

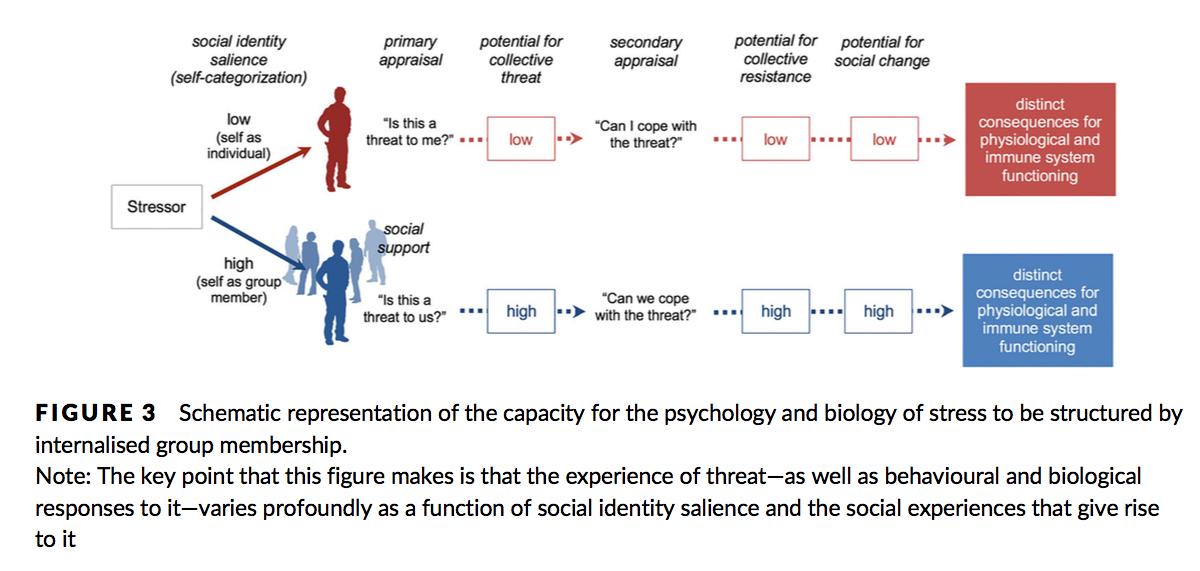

3. Unlock people’s capacity for strength

One of the first things to surface in a crisis are stories about human weakness. But disasters tend to reveal the opposite — that when united by a sense of solidarity, people are (or at least can be) rational, civic-minded, strong

5/n

One of the first things to surface in a crisis are stories about human weakness. But disasters tend to reveal the opposite — that when united by a sense of solidarity, people are (or at least can be) rational, civic-minded, strong

5/n

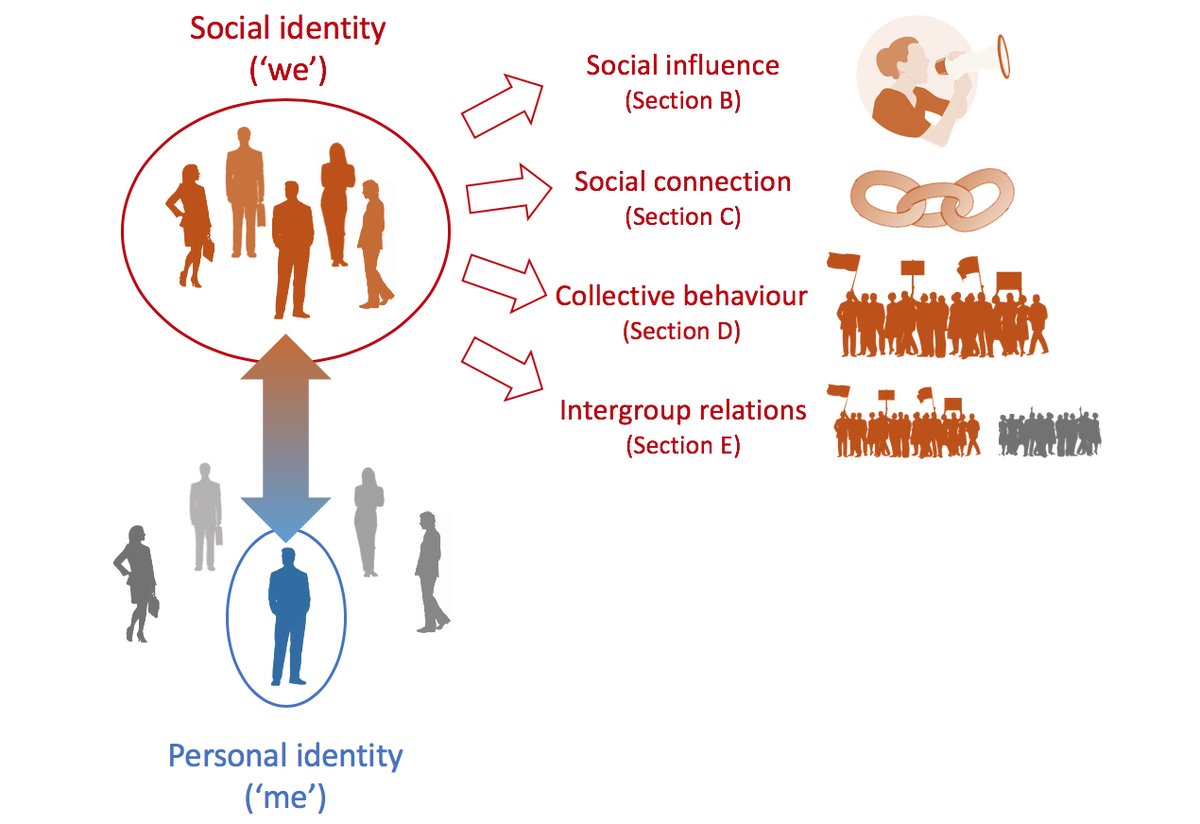

4. Build shared identity

Social identity is the key resource that leaders need to build and tap into in order to mobilise the support and energies of others. Hence the sense that “we're all in this together” is critical to leaders’ appeals to the public and to their success

6/n

Social identity is the key resource that leaders need to build and tap into in order to mobilise the support and energies of others. Hence the sense that “we're all in this together” is critical to leaders’ appeals to the public and to their success

6/n

5. Treat people respectfully

Important as the rhetoric of ‘us’ is, social identity is not just about what leaders say but also about what they do. Leaders need to treat people as ingroup members and actions that create social identity faultlines will harm their leadership

7/n

Important as the rhetoric of ‘us’ is, social identity is not just about what leaders say but also about what they do. Leaders need to treat people as ingroup members and actions that create social identity faultlines will harm their leadership

7/n

6. Define ingroups inclusively

Pre-existing social divisions constrain leaders' ability to promote the sense of a united “us”. In the face of these, they need to engage in particularly vigorous identity leadership to eclipse the previously dominant sense of “us” and “them”

8/n

Pre-existing social divisions constrain leaders' ability to promote the sense of a united “us”. In the face of these, they need to engage in particularly vigorous identity leadership to eclipse the previously dominant sense of “us” and “them”

8/n

7. Appreciate people’s differing needs and circumstances

Leaders need to put in place policies and structures that allow people to have the lived experience of equity. This requires them to recognise that any crisis affects different groups of people very differently

9/n

Leaders need to put in place policies and structures that allow people to have the lived experience of equity. This requires them to recognise that any crisis affects different groups of people very differently

9/n

8. Be empathic rather than punitive

Policies need to be informed by empathy for others' plight. This is no less true when they fail to adhere to relevant guidelines or to ‘do the right thing’ — situations where it is tempting to dish out blame, criticism and punishment

10/n

Policies need to be informed by empathy for others' plight. This is no less true when they fail to adhere to relevant guidelines or to ‘do the right thing’ — situations where it is tempting to dish out blame, criticism and punishment

10/n

9. Provide ongoing support to those who need it

It might seem obvious that leaders need to provide support when and where it is most needed. But, for a range of reasons, they often fail to do this — in part because they fall back on narrow definitions of their ingroup

11/n

It might seem obvious that leaders need to provide support when and where it is most needed. But, for a range of reasons, they often fail to do this — in part because they fall back on narrow definitions of their ingroup

11/n

10. Achieve outcomes that people most value

Obvious too, but relates to the claim that in a crisis people just need charismatic leaders. Against this, we note charisma is something people *bestow* on leaders if they achieve results. If they don’t, their charisma will ebb

12/n

Obvious too, but relates to the claim that in a crisis people just need charismatic leaders. Against this, we note charisma is something people *bestow* on leaders if they achieve results. If they don’t, their charisma will ebb

12/n

11. Prepare groups materially and psychologically for a crisis

Communities respond more adaptively to a crisis and recover more quickly if they go into it with a lot of *social identity capital*. If leaders have eroded this then they put their groups at a huge disadvantage

13/

Communities respond more adaptively to a crisis and recover more quickly if they go into it with a lot of *social identity capital*. If leaders have eroded this then they put their groups at a huge disadvantage

13/

12. Develop identity leadership rather than leader identity

Too much of the leadership literature focuses leaders on the need to be seen as a leader. They need to focus instead on working for their groups. Women tend to be better at this. We should learn from them.

14/

Too much of the leadership literature focuses leaders on the need to be seen as a leader. They need to focus instead on working for their groups. Women tend to be better at this. We should learn from them.

14/

Finally, thanks to a host of people for input and inspiration:

@jetten_j Naomi Ellemers @ProfJohnDrury @shellkryan @cliffordstott @jayvanbavel Kim Peters @KatrienFransen @Tom_Post @f_mols @drCharlie_C @HemaPreya @JordanReutas @mazlanmaskor @Dr_Ilka_Gleibs @realandrewliv

Mum & D

@jetten_j Naomi Ellemers @ProfJohnDrury @shellkryan @cliffordstott @jayvanbavel Kim Peters @KatrienFransen @Tom_Post @f_mols @drCharlie_C @HemaPreya @JordanReutas @mazlanmaskor @Dr_Ilka_Gleibs @realandrewliv

Mum & D

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh