THREAD: Jonah, Moses, and the Cross.

Jonah is traditionally read on Yom Kippur.

Why?

One reason is no doubt its emphasis on repentance.

Thematic and calendrical issues, however, may also play a part.

Jonah is traditionally read on Yom Kippur.

Why?

One reason is no doubt its emphasis on repentance.

Thematic and calendrical issues, however, may also play a part.

Consider the book’s flow of events:

🔹 As the book opens, a threat of judgment looms on the horizon.

🔹 Per the Yom Kippur ritual (on 10th Tishri), lots are cast and Jonah is selected to be sent away.

🔹 As the book opens, a threat of judgment looms on the horizon.

🔹 Per the Yom Kippur ritual (on 10th Tishri), lots are cast and Jonah is selected to be sent away.

🔹 And, four days later (14th Tishri), Jonah builds himself a ‘sukkah’ (‘tabernacle’), in which he rejoices (שמח) (cp. 4.6)—a verb specifically connected with the feast of Tabernacles (Lev. 23.40, Deut. 16.15).

Further connections can also be noted.

But, before we dive into their details, we need to take a step back.

(Christians of all people should make they sure don’t get carried away by divers’ lusts: KJV II Tim. 3.6.)

But, before we dive into their details, we need to take a step back.

(Christians of all people should make they sure don’t get carried away by divers’ lusts: KJV II Tim. 3.6.)

--- A PROPHET ON THE RUN ---

Jonah’s distinctive as a prophet is undoubtedly his decision to run away from his God.

How many other prophetic books open with a description of their author’s disobedience?

Jonah’s distinctive as a prophet is undoubtedly his decision to run away from his God.

How many other prophetic books open with a description of their author’s disobedience?

From its very outset, then, the book of Jonah invites us to ponder Jonah’s character and why he behaves as he does.

And in 4.2 we find out.

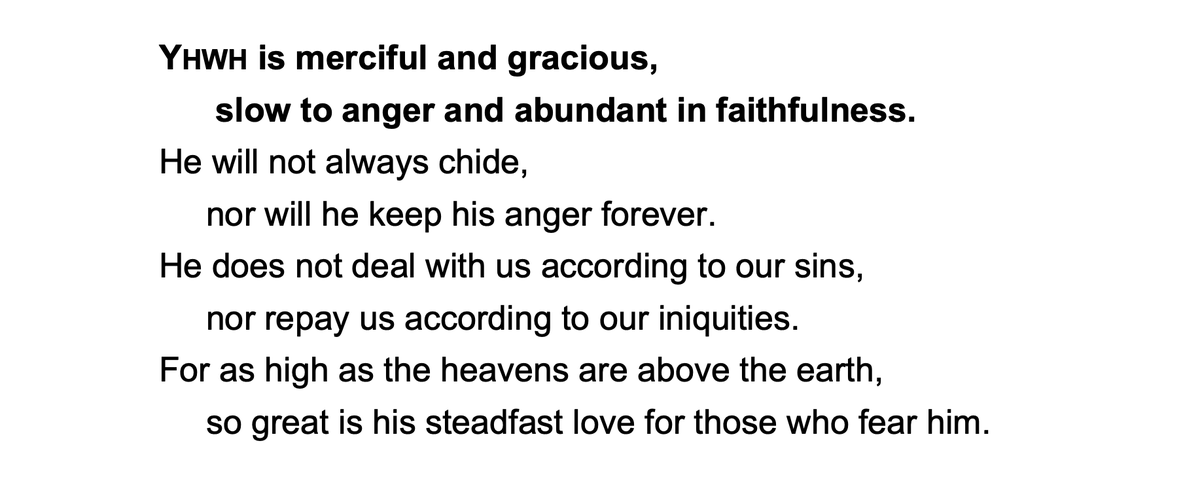

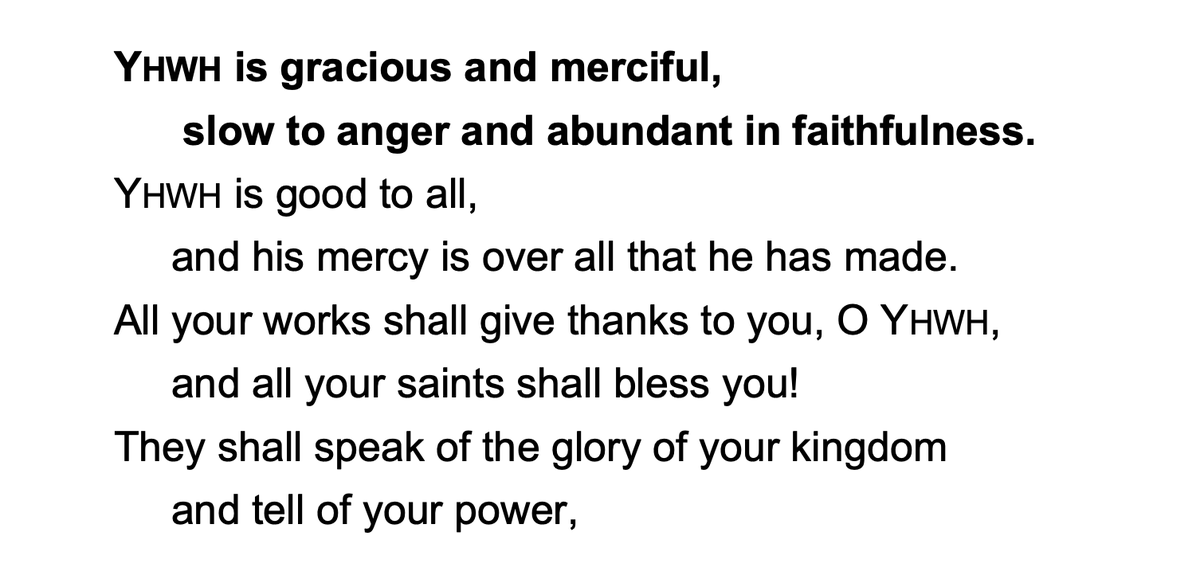

Because Jonah knows YHWH to be ‘a gracious God and merciful, slow to anger, abundant in faithfulness, and one who relents from disaster’.

And in 4.2 we find out.

Because Jonah knows YHWH to be ‘a gracious God and merciful, slow to anger, abundant in faithfulness, and one who relents from disaster’.

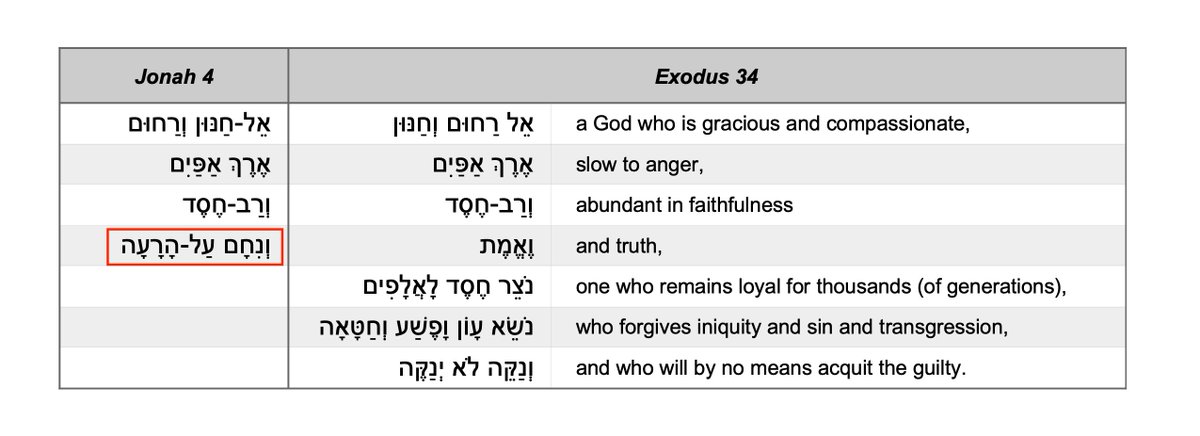

Jonah’s description of YHWH should ring a bell.

It’s similar to YHWH’s own description of himself when he reveals his glory to Moses (Exod. 34.6–7).

It’s not, however, exactly the same.

It differs from YHWH’s self-description in an important respect.

It’s similar to YHWH’s own description of himself when he reveals his glory to Moses (Exod. 34.6–7).

It’s not, however, exactly the same.

It differs from YHWH’s self-description in an important respect.

Whereas YHWH describes himself as a God who is ‘true’ (אמת), Jonah describes him as a God who ‘relents of (his plans to bring) disaster’ on people (נִחָם על הרעה).

Why?

What exactly does Jonah take YHWH’s ‘truthfulness’ (אמת) to signify?

The next verse may provide us with a clue.

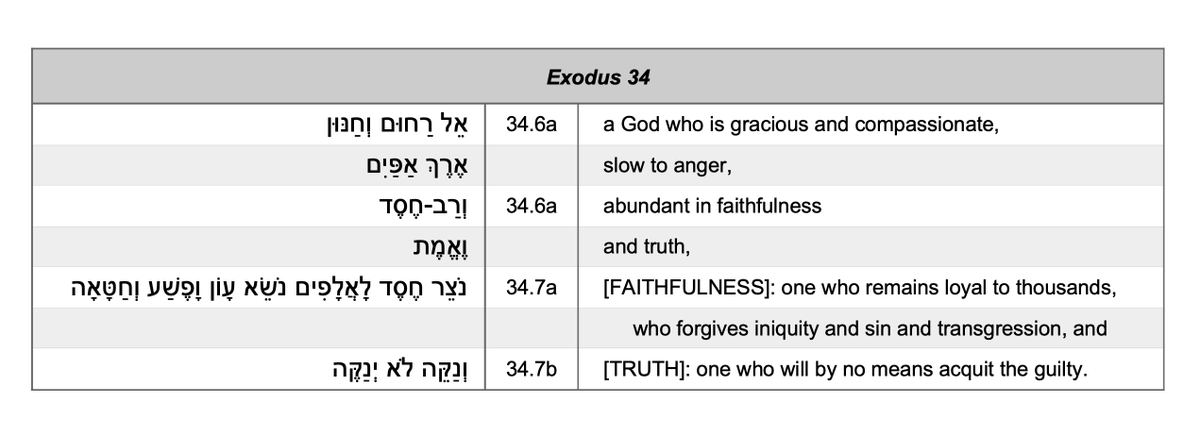

YHWH is a God, we’re told, who remains loyal for thousands (of generations)—who pardons iniquity and sin and transgression, and by no means acquits the guilty.

What exactly does Jonah take YHWH’s ‘truthfulness’ (אמת) to signify?

The next verse may provide us with a clue.

YHWH is a God, we’re told, who remains loyal for thousands (of generations)—who pardons iniquity and sin and transgression, and by no means acquits the guilty.

Which is an unusual statement.

How can one forgive sin (34.7a) unless one acquits the guilty (34.7b)? The forgiveness of sin just is the acquittance of the guilty, isn’t it?

How can one forgive sin (34.7a) unless one acquits the guilty (34.7b)? The forgiveness of sin just is the acquittance of the guilty, isn’t it?

If so, 34.7a and 34.7b must describe YHWH’s treatment of two distinct groups of people,

namely those who are on the right side of his mercy/covenant and those who are on the wrong side of it.

namely those who are on the right side of his mercy/covenant and those who are on the wrong side of it.

I therefore take 34.7a and 34.7b to (respectively) fill out 34.6’s reference to ‘faithfulness’ (חסד) and ‘truth’ (אמת).

YHWH deals with those within the covenant in ‘faithfulness’ (חסד)—that is to say, rather than reject them when they go astray, he takes away their sin and thereby preserves his covenant relationship with them (cp. Neh. 1.5)—,

while YHWH deals with those on the wrong side of the covenant in ‘truth’ (אמת)—that is to say, he punishes their sin as it deserves to be punished.

In the context of Exodus 34, then, I take the words ‘faithfulness’ (חסד) and ‘truth’ (אמת) to describe different and to some extent opposed divine attributes,

which would explain how Psa. 85 can look forward to a time when these attributes are ‘brought together’ (נפגשו).

which would explain how Psa. 85 can look forward to a time when these attributes are ‘brought together’ (נפגשו).

The difference between YHWH’s covenant ‘faithfulness’ and ‘truth’ is reflected in the Bible’s quotations of Exodus 34.

When a Biblical text ends its quotation of Exodus 34.6 at the word ‘faithfulness’ (חסד), it goes on to describe (only) YHWH’s acts of mercy/preservation, as can be seen in Nehemiah 9.17ff.

Meanwhile, the only Biblical text we have which quotes Exodus 34.6 in its entirety—i.e., to end at the word ‘truth’ (אמת)—goes on to describe both YHWH’s acts of both mercy *and* his acts of judgment (Psa. 86.15):

Jonah’s ‘problem’ with YHWH can, therefore, be summarised as follows.

The Ninevites have forsaken their chance to be dealt with in ‘faithfulness’ (חַסְדָּם יַעֲזֹבוּ) (cp. 2.8).

The Ninevites have forsaken their chance to be dealt with in ‘faithfulness’ (חַסְדָּם יַעֲזֹבוּ) (cp. 2.8).

It’s obvious, therefore, what YHWH should do (or at least it’s obvious to Jonah). Like ch. 4’s plant, Nineveh should be destroyed overnight.

In ch. 4, however, to his horror, Jonah finds out YHWH doesn’t share his opinions.

YHWH decides to go soft on the Ninevites.

In ch. 4, however, to his horror, Jonah finds out YHWH doesn’t share his opinions.

YHWH decides to go soft on the Ninevites.

Rather than give the Ninevites what they deserve, he ‘relents’, which greatly rankles Jonah.

As a prophet, Jonah is all about YHWH’s ‘truthfulness’ (אמת).

Indeed, YHWH’s truthfulness is part of his father’s name—viz. ‘Amittai’ (אֲמִתַּי)—,

As a prophet, Jonah is all about YHWH’s ‘truthfulness’ (אמת).

Indeed, YHWH’s truthfulness is part of his father’s name—viz. ‘Amittai’ (אֲמִתַּי)—,

which is short for ‘ YHWH is truth’ (cp. the name יִשְׁמְרַי, which is an abbrevation of ישמריהו).

And yet, in his salvation of the Ninevites, YHWH has compromised his truthfulness.

And yet, in his salvation of the Ninevites, YHWH has compromised his truthfulness.

Consequently, in ch. 4, after one of the most successful evangelistic campaigns known to mankind, we find Jonah on the outskirts of Nineveh, depressed and dejected.

--- SOME QUESTIONS ---

So, was Jonah right to feel as he did?

Well, yes and no.

That Jonah didn’t like the way YHWH had backtracked was understandable.

Jonah didn’t want to be known as a false prophet.

And, given the penalty (cp. Deut. 13), who could blame him?

So, was Jonah right to feel as he did?

Well, yes and no.

That Jonah didn’t like the way YHWH had backtracked was understandable.

Jonah didn’t want to be known as a false prophet.

And, given the penalty (cp. Deut. 13), who could blame him?

Yet Jonah had overlooked a number of important details.

First, the nature of his prophecy.

‘Forty more days’, Jonah had declared, ‘and Nineveh will be נהפכת’—a phrase which is generally rendered ‘Nineveh will be overthrown’,

First, the nature of his prophecy.

‘Forty more days’, Jonah had declared, ‘and Nineveh will be נהפכת’—a phrase which is generally rendered ‘Nineveh will be overthrown’,

but can equally well be rendered ‘Nineveh will be changed/converted!’ (cp. the sense of נהפוך in Est. 9.1 or הפכת in Psa. 41.3).

Contra Jonah’s concern, then, YHWH hadn’t made a false prophet out of Jonah.

Contra Jonah’s concern, then, YHWH hadn’t made a false prophet out of Jonah.

Jonah’s prophecy had been fulfilled, just not in the way he’d wanted/expected. And, sadly, while Nineveh had undergone a change of heart, Jonah hadn’t—which becomes the subject matter of chapter 4.

Second, Jonah had overlooked the context of the words he’d just (partially) quoted.

In the days of Exodus 34, Israel weren’t in a good way.

They’d emerged from the Red Sea,

entered into a covenant with YHWH which prohibited idolatry,

In the days of Exodus 34, Israel weren’t in a good way.

They’d emerged from the Red Sea,

entered into a covenant with YHWH which prohibited idolatry,

and promptly engaged in that very sin (with the help of some golden calves).

Israel therefore deserved to be destroyed, just as Egypt had been.

But, despite the fact YHWH had said he’d destroy Israel, he chose to have mercy on her.

Israel therefore deserved to be destroyed, just as Egypt had been.

But, despite the fact YHWH had said he’d destroy Israel, he chose to have mercy on her.

And, significantly, Israel’s preservation in Exodus 32–34 is described in very similar terms to Nineveh’s.

To spell these similarities out:

🔹 Just as Nineveh was ‘a great city’ (עיר גדולה) which had done ‘evil’ (רעה) in God’s sight, so Israel was ‘a great nation’ (גוי גדול) which had committed a ‘great sin’ (חטאה גדולה) in God’s sight.

🔹 Just as Nineveh was ‘a great city’ (עיר גדולה) which had done ‘evil’ (רעה) in God’s sight, so Israel was ‘a great nation’ (גוי גדול) which had committed a ‘great sin’ (חטאה גדולה) in God’s sight.

🔹 Just as Nineveh’s judgment was due to fall on them at the end of a forty-day period, so also was Israel’s.

🔹 Just as the king of Nineveh commanded his cattle not to eat fodder (אַל־יִרְעוּ) as the nation sought YHWH’s favour, so Moses commanded Israel’s cattle not to graze on Mount Sinai as he went up to meet with YHWH. (The phrase אַל־יִרְעוּ occurs only in Jonah 3 and Exodus 34.)

🔹 Just as the king sought to persuade YHWH to relent (נחם) and turn from his anger (שוב מחרון אפו), so also did Moses (Exod. 32.12).

🔹 And, just as YHWH did in fact relent (נחם) from the disaster he said he’d bring on Nineveh (הָרָעָה אֲשֶׁר דִּבֶּר לַעֲשׂוֹת), so also YHWH relented in Israel’s case (הָרָעָה אֲשֶׁר דִּבֶּר לַעֲשׂוֹת).

And, had he not done so, Israel would never have made it out of the wilderness.

That YHWH (occasionally) relented of his plans to bring disaster on a people/nation was not, therefore, a fact Jonah should have been aggrieved at, but a fact he should have rejoiced in,

That YHWH (occasionally) relented of his plans to bring disaster on a people/nation was not, therefore, a fact Jonah should have been aggrieved at, but a fact he should have rejoiced in,

not least because Nineveh’s response to their situation is described in far more impressive terms than Israel’s.

Whereas the king of Nineveh took off his robe, covered himself in sackcloth, and commanded his people to follow suit, the Israelites merely laid aside their adornments/jewellery for a while.

And whereas the Ninevites called out to God, fasted, and turned from evil, the Israelites merely bemoaned (אבל) their state, and only Moses abstained from food and drink (Exod. 33.4–6, 34.28).

Moreover, in contrast to Israel’s ‘great’ sin (חטאה גדולה), Nineveh’s evil is one of the few things not to be described as ‘great’ in the book of Jonah.

Hence, just as Jesus said the Ninevites’ repentance brought shame on his 1st cent. AD audience (Matt. 12.41), so the Ninevites’ repentance could be said to have brought shame on previous generations of Israelites.

Indeed, Rashi claims Jonah went to Tarshish precisely because he knew the Gentiles/idolaters were ‘on the verge of repentance’ (קרובי תשובה) and didn’t want to make the Israelites’ failure to repent look even worse.

Third, Jonah had overlooked the extent of YHWH’s sovereignty and greatness.

True, the nature of YHWH’s covenant meant some would receive mercy while others wouldn’t (cp. 4.2 w. Exod. 34.6–7).

But Jonah had ignored an important aspect of YHWH’s self-description in Exodus 34.

True, the nature of YHWH’s covenant meant some would receive mercy while others wouldn’t (cp. 4.2 w. Exod. 34.6–7).

But Jonah had ignored an important aspect of YHWH’s self-description in Exodus 34.

Before YHWH revealed himself as a God of ‘grace’ (חנון) and ‘mercy’ (רחום), YHWH made the all-important declaration, ‘I show grace to those whom I desire to show grace (חַנֹּתִי אֶת-אֲשֶׁר אָחֹן)...

...and ‘I show mercy to those whom I desire to show mercy’ (רִחַמְתִּי אֶת-אֲשֶׁר אֲרַחֵם).

Grace and mercy were YHWH’s to dispense as he pleased, and YHWH’s plans for the world were far greater and expansive than Jonah cared to imagine—a fact which, deep down, Jonah knew.

Grace and mercy were YHWH’s to dispense as he pleased, and YHWH’s plans for the world were far greater and expansive than Jonah cared to imagine—a fact which, deep down, Jonah knew.

Indeed, Jonah himself had referred to YHWH as ‘the God of heaven’, and as the one who made not only Israel, but ‘the sea and the dry land’ (1.9).

Jonah had seen YHWH do (in the sailors’ words) exactly ‘as he pleased’ (1.14).

And, when the chips were down, Jonah had realised ‘salvation belonged to YHWH’ (ישועתה ליהוה) (cp. 2.9).

And, when the chips were down, Jonah had realised ‘salvation belonged to YHWH’ (ישועתה ליהוה) (cp. 2.9).

Petulantly, however, Jonah had convinced himself YHWH was a merely local deity, whose presence he could ignore and/or flee from.

And Jonah had been shown to be badly mistaken.

And Jonah had been shown to be badly mistaken.

After all, how can you compete with a God who can ‘throw’ a wind to the earth so as to stir up the sea and lead a ship to (decide?) to splinter in pieces...

...in such a way as to cause its sailors to throw/cast lots and subsequently throw Jonah overboard...

...in such a way as to cause its sailors to throw/cast lots and subsequently throw Jonah overboard...

...just in time for him to be swallowed by a fish (in the appropriate place at the appropriate time) and spewed out on the dry land three days later?

Suffice it to say, YHWH’s ways were far beyond Jonah’s, as YHWH continues to demonstrate in ch. 4.

Suffice it to say, YHWH’s ways were far beyond Jonah’s, as YHWH continues to demonstrate in ch. 4.

--- CHAPTER 4 ---

As Jonah sits on the outskirts of Nineveh and prepares to watch the city go up in flames, YHWH causes a plant to grow out of the ground, which provides Jonah with some much-needed shade from the sun.

As Jonah sits on the outskirts of Nineveh and prepares to watch the city go up in flames, YHWH causes a plant to grow out of the ground, which provides Jonah with some much-needed shade from the sun.

The plant is said to ‘deliver’ (להציל) Jonah from ‘evil’ (רעה), and Jonah reacts to its presence extravagantly.

He rejoices with ‘great joy’ (שמחה גדולה)—an expression elsewhere associated only with the construction of the Temple, the coronation of Solomon, and the reinstitution of long forgotten feasts (2 Chr. 30, Neh. 8), i.e., epochal events.

In light of Jonah’s reaction, YHWH asks some difficult questions.

If Jonah could legitimately be overjoyed by the (apparently) fortuitous arrangement of the natural world, YHWH asks, then why shouldn’t he, YHWH, be overjoyed by his restoration of the human world?

If Jonah could legitimately be overjoyed by the (apparently) fortuitous arrangement of the natural world, YHWH asks, then why shouldn’t he, YHWH, be overjoyed by his restoration of the human world?

If Jonah could be ‘concerned’ (חוס) about a mere plant which was there one minute and gone the next, and which YHWH himself ‘grew’ (גִּדֵּל), then why shouldn’t he, YHWH, have ‘spared’ (חוס) a ‘great’ (גָּדֹל) city which had existed since nations were established (cp. Gen. 10)—…

…a question which plays on the semantic range of the verb חוס (cp. Gen. 45.20, Joel 2.17)?

And, if Jonah could be overjoyed by the prevention of an ‘evil’ (רעה) as minor as sunstroke, then why shouldn’t he, YHWH, want to avert a national ‘disaster’ (רעה) and turn a whole city from its ‘evil’ ways (רעה) (cp. 3.8–10)?

Jonah never gets to answer these questions (since the book comes to an apparently premature end), but he doesn’t need to. The implication is obvious:

Jonah’s view of the world is far too small and self-centred.

Jonah’s view of the world is far too small and self-centred.

--- AND YET… ---

For all its faults, Jonah’s response to Nineveh’s salvation is instructive, and is one we’re intended to grapple with and to learn from.

Israel’s salvation was costly.

Her redemption from the land of Egypt came at a cost (Egypt’s: Isa. 43.3).

For all its faults, Jonah’s response to Nineveh’s salvation is instructive, and is one we’re intended to grapple with and to learn from.

Israel’s salvation was costly.

Her redemption from the land of Egypt came at a cost (Egypt’s: Isa. 43.3).

The atonement of her sins came at a cost (various animals’: Lev. 17.11).

And, with one notable exception (to be discussed shortly), the acts of salvation mentioned (and/or alluded to) in the book of Jonah came at a cost.

And, with one notable exception (to be discussed shortly), the acts of salvation mentioned (and/or alluded to) in the book of Jonah came at a cost.

In the aftermath of Israel’s ‘great sin’ with the golden calf, a plague afflicted Israel and a priest (Moses) was required to atone for Israel’s sin (Exod. 32.30, 35).

In the aftermath of the sailors’ salvation, the sailors offered sacrifices to YHWH in recompense for the life of Jonah (1.14, 16).

And, from the belly of Sheol, Jonah looked towards YHWH’s temple—the house of sacrifice—and promised to render him sacrifices (cp. 2.4, 7, 9 w. 2 Chr. 7.12).

We thus come to our exception:

the Ninevites.

We thus come to our exception:

the Ninevites.

In the most dramatic instance of salvation in the book of Jonah—an event which has come to associate the book with Yom Kippur—, sacrifice and atonement are not mentioned at all.

Forgiveness seems too readily available, which clearly rankled Jonah—and not unreasonably.

Forgiveness seems too readily available, which clearly rankled Jonah—and not unreasonably.

Israel’s sacrificial system was intended (among other things) to teach the Israelites a simple yet vital lesson:

the transgression of God’s law couldn’t just be overlooked.

Atonement was necessary, which was why Israel had a tabernacle, a priesthood, and later a temple.

the transgression of God’s law couldn’t just be overlooked.

Atonement was necessary, which was why Israel had a tabernacle, a priesthood, and later a temple.

How, then, could YHWH simply forgive the Ninevites for their evil ways?

Or, to put the question in Jonah’s terms, how could YHWH forgive the Ninevites and still be said to deal with them in ‘truth’ (אמת)?

Or, to put the question in Jonah’s terms, how could YHWH forgive the Ninevites and still be said to deal with them in ‘truth’ (אמת)?

More on that in a few days I hope.

TO BE CONTINUED...

(Please RT if helpful.)

TO BE CONTINUED...

(Please RT if helpful.)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh