THREAD: Jonah, Moses, and the Cross (Part II).

SUB-TITLE: Where Mercy and Truth Meet.

Last time round (link below), we considered some connections between the story of Jonah and the concept of atonement.

SUB-TITLE: Where Mercy and Truth Meet.

Last time round (link below), we considered some connections between the story of Jonah and the concept of atonement.

https://twitter.com/JamesBejon/status/1335165443947057152

Here, I’ll try to ponder some of their deeper implications.

Missionary Report from Nineveh, the 10th Year of Jeroboam:

‘Dear brothers and sisters. Our labours in Assyria have been burdensome in recent months. Much to our frustration, whole cities have turned to the Lord in repentance and faith...’

‘Dear brothers and sisters. Our labours in Assyria have been burdensome in recent months. Much to our frustration, whole cities have turned to the Lord in repentance and faith...’

I’d be pretty surprised to find a missionary report which began in such a manner.

And, at first blush, Jonah’s response to the Ninevites’ salvation seems equally incongruous.

Why would a prophet be upset because repented at his message?

The answer is revealed to us in 4.2.

And, at first blush, Jonah’s response to the Ninevites’ salvation seems equally incongruous.

Why would a prophet be upset because repented at his message?

The answer is revealed to us in 4.2.

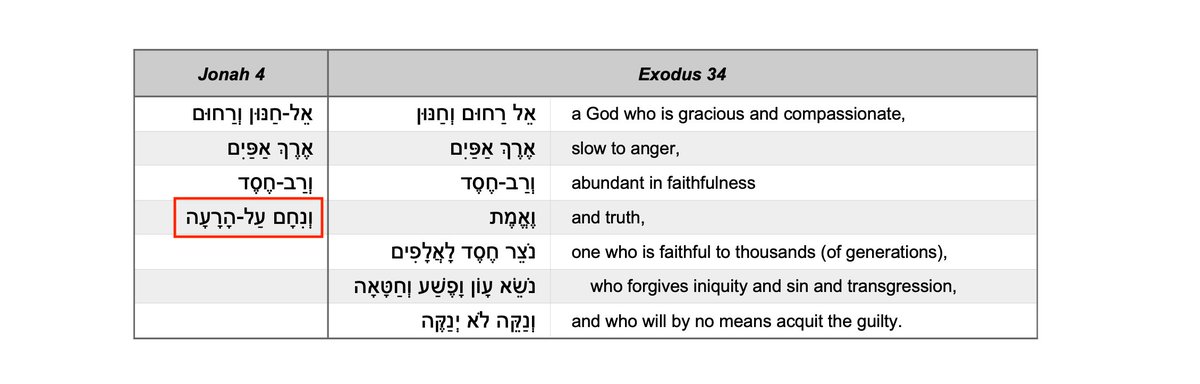

As we know, Jonah has a major issue with how YHWH has chosen to deal with Nineveh,

which he reveals in his (mis)quotation of YHWH’s self-description (Exodus 34.6–7).

Where YHWH refers to himself as a God of ‘truth’ (אמת), Jonah refers to him as a God who ‘relents’.

which he reveals in his (mis)quotation of YHWH’s self-description (Exodus 34.6–7).

Where YHWH refers to himself as a God of ‘truth’ (אמת), Jonah refers to him as a God who ‘relents’.

The difference is significant.

In the context of Exodus 34.6–7, YHWH’s ‘faithfulness’ refers to the way he forgives his covenant people,

In the context of Exodus 34.6–7, YHWH’s ‘faithfulness’ refers to the way he forgives his covenant people,

while his ‘truth’ (אמת) refers to the way he gives others what they deserve, i.e., justice. (Note, however, the contrast between the tense/aspect/whatever of נקה לא ינקה and נֹצֵר/נֹשֵׂא: YHWH brings people to justice in his own time.)

The Bible’s own use of Exodus 34 is consistent with such a notion.

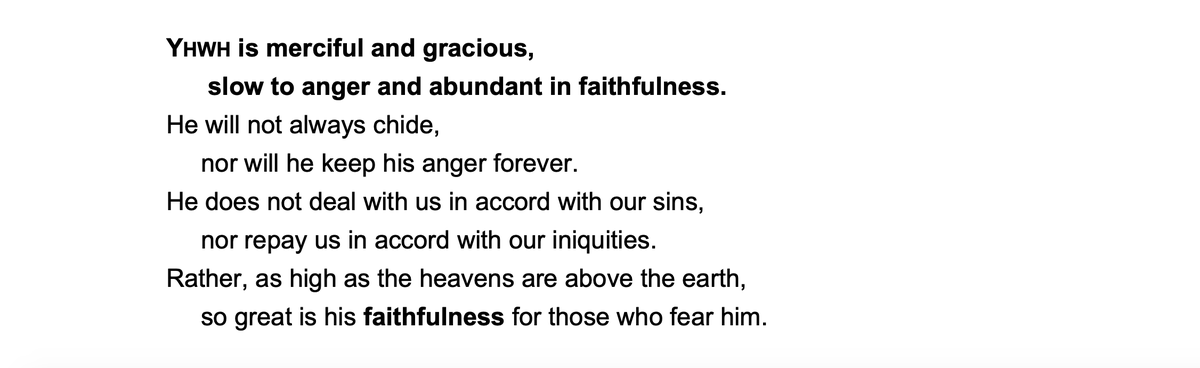

When a Biblical text refers to Exodus 34.6 and ends its reference at the word ‘faithfulness’ (חסד), what follows focuses on YHWH’s acts of *mercy/preservation*,

as can be seen in Nehemiah 9.17, Psalm 103.8 (below), and Psalm 145.8.

as can be seen in Nehemiah 9.17, Psalm 103.8 (below), and Psalm 145.8.

Meanwhile, when the Biblical text refers to Exodus 34.6 in its entirety, and hence ends at the word ‘truth’ (אמת), what follows describes both YHWH’s acts of mercy and his acts of judgment (Psa. 86.15).

And, instructively, when judgment finally overtakes Nineveh (after its reprieve in Jonah’s day), Nahum alludes to Exodus 34.6 (‘YHWH is slow to anger’)...

...and then goes on to quote 34.7’s ‘truth’ (אמת) related component:

‘YHWH will by no means clear the guilty’ (Nah. 1.3).

...and then goes on to quote 34.7’s ‘truth’ (אמת) related component:

‘YHWH will by no means clear the guilty’ (Nah. 1.3).

Jonah’s issue is, therefore, as follows.

As a prophet, he is all about YHWH’s ‘truthfulness’ (אמת). Indeed, he’s the son of a man whose name means ‘YHWH is truth’ (אֲמִתַּי).

And yet, by means of his salvation of the Ninevites, YHWH has compromised on his truthfulness,

As a prophet, he is all about YHWH’s ‘truthfulness’ (אמת). Indeed, he’s the son of a man whose name means ‘YHWH is truth’ (אֲמִתַּי).

And yet, by means of his salvation of the Ninevites, YHWH has compromised on his truthfulness,

which has rankled Jonah.

For all its faults, however, Jonah’s response to Nineveh’s salvation has positive lessons to teach us,

and is one we’re intended to grapple and perhaps even resonate with.

For all its faults, however, Jonah’s response to Nineveh’s salvation has positive lessons to teach us,

and is one we’re intended to grapple and perhaps even resonate with.

Consider Jonah’s situation.

Jonah knew Israel’s salvation was a costly business.

Israel’s redemption from the land of Egypt came at a cost (Egypt’s: Isa. 43.3).

The atonement of her sins came at a cost (various animals’: Lev. 17.11).

Jonah knew Israel’s salvation was a costly business.

Israel’s redemption from the land of Egypt came at a cost (Egypt’s: Isa. 43.3).

The atonement of her sins came at a cost (various animals’: Lev. 17.11).

And, with one notable exception (to be discussed in a moment), the acts of salvation alluded to in the book of Jonah came at a cost:

🔹 In the aftermath of Israel’s ‘great sin’ with the golden calf, a plague afflicted Israel and a priest (Moses) was required to atone for Israel’s sin (Exod. 32.30, 35).

🔹 In the aftermath of the sailors’ salvation, the sailors offered sacrifices to YHWH in recompense for the life of Jonah (1.14, 16).

🔹 And, from the belly of Sheol, Jonah looked towards YHWH’s temple (‘house of sacrifice’) and vowed to render him sacrifices (cp. 2.4, 7, 9).

🔹 And, from the belly of Sheol, Jonah looked towards YHWH’s temple (‘house of sacrifice’) and vowed to render him sacrifices (cp. 2.4, 7, 9).

We thus come to our exception: the salvation of the Ninevites.

In the central instance of salvation in the book of Jonah—an event which has come to associate the book with Yom Kippur—, sacrifice and atonement are not mentioned at all.

In the central instance of salvation in the book of Jonah—an event which has come to associate the book with Yom Kippur—, sacrifice and atonement are not mentioned at all.

Forgiveness seems to have been too readily available, which clearly irked Jonah—and perhaps not unreasonably.

Israel’s sacrificial system was intended (among other things) to teach the Israelites an important lesson: the transgression of God’s law couldn’t be overlooked.

Israel’s sacrificial system was intended (among other things) to teach the Israelites an important lesson: the transgression of God’s law couldn’t be overlooked.

Atonement was necessary, which was why Israel had a tabernacle, a priesthood, and later a temple.

How, then, could YHWH simply forgive the Ninevites for their evil ways?

How, then, could YHWH simply forgive the Ninevites for their evil ways?

Or, to put the question in Jonah’s terms, how could YHWH forgive the Ninevites (show them חסד) and still be said to deal with them in ‘truth’ (אמת)?

The answer takes us well beyond the book of Jonah, but will (I hope) be worthwhile to consider.

It consists of four main strands.

The answer takes us well beyond the book of Jonah, but will (I hope) be worthwhile to consider.

It consists of four main strands.

The first concerns what Jonah seems quick to forget.

As we’ve noted, the Ninevites weren’t the only people to have needed YHWH to ‘relent’ of one of his previous declarations.

As we’ve noted, the Ninevites weren’t the only people to have needed YHWH to ‘relent’ of one of his previous declarations.

Soon after the birth of Israel as a nation, the Israelites needed YHWH to relent in order for them to make it past their first year.

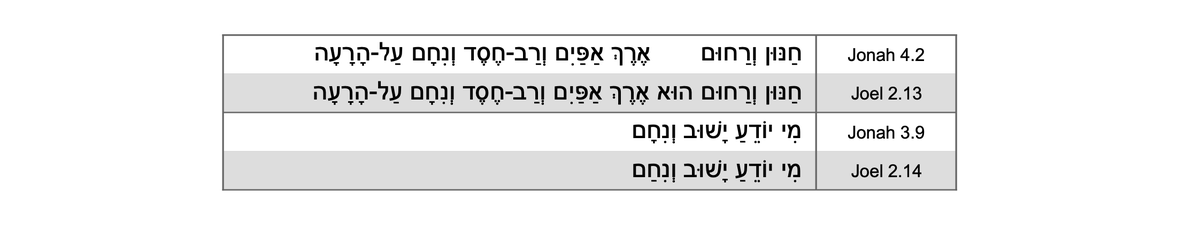

The connection between the books of Jonah and Joel further

problematises Jonah’s attitude.

The connection between the books of Jonah and Joel further

problematises Jonah’s attitude.

Jonah’s description of YHWH in 4.2 is a carbon copy of Joel’s (Joel 2.13), while the king of Nineveh’s exhortation to his people in 3.9 is a carbon copy of Joel’s (Joel 2.14),

…which is significant.

If YHWH shouldn’t have responded to Nineveh’s repentance, then why should he have responded to Israel’s (in Joel’s day)?

As such, Jonah’s ‘problem’ with YHWH’s behaviour was part of a much bigger issue—the issue of how YHWH could forgive anyone at all...

If YHWH shouldn’t have responded to Nineveh’s repentance, then why should he have responded to Israel’s (in Joel’s day)?

As such, Jonah’s ‘problem’ with YHWH’s behaviour was part of a much bigger issue—the issue of how YHWH could forgive anyone at all...

...and not compromise his ‘truthfulness’ (אמת).

The second strand of our answer concerns the notion of sacrifice.

In and by means of his appointed sacrifices, YHWH demonstrates both his ‘faithfulness’ and his ‘truth’.

Consider the events of the Passover,

In and by means of his appointed sacrifices, YHWH demonstrates both his ‘faithfulness’ and his ‘truth’.

Consider the events of the Passover,

in which YHWH judges a land full of false gods (owned by the Egyptians and Israelites alike: Exod. 12.12, Ezek. 20.7–10).

A death takes place in each and every house in Egypt: either the death of a firstborn or the death of a lamb.

A death takes place in each and every house in Egypt: either the death of a firstborn or the death of a lamb.

YHWH thus affirms the truth of what he has said about sin—namely that sin leads to death—and is at the same time faithful to his people (insofar as he preserves his covenant with them).

And the same principle underlies the sacrificial system as a whole.

And the same principle underlies the sacrificial system as a whole.

Like deliverance from Egypt’s judgment, atonement comes ‘at the expense of life’ (בַּנֶּפֶשׁ) (Lev. 17.11).

As Rashi says by way of commentary on Lev. 17.11, ‘One life comes and atones for another life’ (תבוא נפש ותכפר על הנפש).

As Rashi says by way of commentary on Lev. 17.11, ‘One life comes and atones for another life’ (תבוא נפש ותכפר על הנפש).

Our third strand concerns the sacrificial system’s inadequacies.

True, the sacrificial system provided atonement, but it wasn’t ‘the finished article’, nor was it intended to be.

Consider some of its limitations:

True, the sacrificial system provided atonement, but it wasn’t ‘the finished article’, nor was it intended to be.

Consider some of its limitations:

🔹 The sacrificial system provided atonement for few if any intentional sins.

It could do nothing, for instance, to atone for the sins of the idolater, the murderer, or the adulterer.

And yet such people could, somehow, be forgiven (e.g., David).

It could do nothing, for instance, to atone for the sins of the idolater, the murderer, or the adulterer.

And yet such people could, somehow, be forgiven (e.g., David).

🔹 While some aspects of the Mosaic law are described in permanent terms (e.g., the significance of Sabbaths), the sacrificial system isn’t one of them.

Rather, the Torah envisages a time when the people are expelled from Israel,

Rather, the Torah envisages a time when the people are expelled from Israel,

which leaves the sacrificial system in disrepair (Lev. 26) and the land in need of atonement (Deut. 32.43)—a problem which the sacrificial system itself can’t solve.

🔹 The effects of the sacrificial system were only temporary, as was illustrated by the high-priest’s need to repeat the same Yom Kippur sacrifice each year (cp. Heb. 10.1–4).

🔹 And the sacrificial system was destined to be replaced by Ezekiel’s, which differs from it in a number of important respects.

For Ezekiel, Israel was not the unblemished nation she took herself to be.

For Ezekiel, Israel was not the unblemished nation she took herself to be.

She was the child of an Amorite father and a Hittite mother (16.3), plagued by sin from her youth upwards (16.15ff.).

Even in the aftermath of the exodus, she emerged laden down by idols (Ezek. 20, 23.1–4).

Even in the aftermath of the exodus, she emerged laden down by idols (Ezek. 20, 23.1–4).

And her temple and land had come to inherit her uncleanness (e.g., Ezek. 9.9, 22.26, 36.17–18, 43.8).

Israel was, therefore, in need of a new and untainted sacrificial system, which is precisely what Ezekiel 40–48 portrays—a system which is remote and otherworldly,

Israel was, therefore, in need of a new and untainted sacrificial system, which is precisely what Ezekiel 40–48 portrays—a system which is remote and otherworldly,

located on the plateau of a high mountain,

separated from its environs by an enormous border of ‘holy land’,

attended by an exclusive (Zadokite) priesthood (and bereft of ‘commoners’),

free from the sweat associated with creation’s curse (cp. 44.18 w. Gen. 3.19),

separated from its environs by an enormous border of ‘holy land’,

attended by an exclusive (Zadokite) priesthood (and bereft of ‘commoners’),

free from the sweat associated with creation’s curse (cp. 44.18 w. Gen. 3.19),

built without human assistance,

run on its own (non-Mosaic) timetable and regulations,

and sacral/idealistic in measurement (e.g., 500 x 500 cubits, amidst a 25,000 x 10,000 plot of land), i.e., free from the normal constraints of geography and politics.

run on its own (non-Mosaic) timetable and regulations,

and sacral/idealistic in measurement (e.g., 500 x 500 cubits, amidst a 25,000 x 10,000 plot of land), i.e., free from the normal constraints of geography and politics.

In other words, it is an untainted eschatological sacrificial system, without the inherent flaws and limitations of the Mosaic system.

The fourth and final strand of our answer concerns the power of human life to atone for sin.

If human life is of greater value than animal life (Gen. 1, Exod. 21.16 w. 22.1, etc.), and if animal life can atone for sin, then it would follow, kal vachomer (i.e., a fortiori), that human life can atone for sin even more effectively.

And, woven throughout the Torah’s description of the sacrificial system, we find allusions to precisely such a notion.

🔹 In Exodus 32, in between the passages where the sacrificial system is prescribed (chs. 25–31) and inaugurated (chs. 34–40), Moses ascends into YHWH’s presence and offers his life as an atonement (כפר) for his people’s sins (Exod. 32.30–32),

which, although it is not ‘accepted’, preserves Israel’s existence. (The first act of atonement recorded in Scripture is thus effected by the Akedah-like offer of a human life.)

🔹 In Numbers 25, after many of the Israelites have lapsed into idolatry and a plague has afflicted the people, the priest Phinehas slays a representative ringleader,

which is said to make atonement (כפר) for Israel and halt the plague.

which is said to make atonement (כפר) for Israel and halt the plague.

(By the same kal vachomer logic as before, then, one would think the sacrifice of a righteous representative of a guilty party could atone for sin all the more effectively.)

🔹 And, in Numbers 35, at the end of its account of the cities of refuge, the death of the high priest is said to allow manslayers to return to their hometowns (Num. 35.32), as if his death provides atonement (כפר) for their sins (Num. 35.33),

which is the view adopted in the Talmud (b. Makkot 11b).

The commentator Jacob Milgrom concurs. ‘As the high priest atones for Israel’s sins through his life of cultic service’, he says, ‘so he atones for homicide through his death’.

The commentator Jacob Milgrom concurs. ‘As the high priest atones for Israel’s sins through his life of cultic service’, he says, ‘so he atones for homicide through his death’.

Hence, what neither exile nor ransom payments (כפרים) nor the blood of animals could accomplish over the course of the high priest’s life, the blood of the high priest accomplishes at his death.

Such indications of the power of human life to atone for sin find numerous echoes throughout the Biblical narrative,

and find their ultimate fulfilment in the figure of Isaiah 53’s servant—an exalted and priestly figure who, like Moses, intercedes for his people,

and find their ultimate fulfilment in the figure of Isaiah 53’s servant—an exalted and priestly figure who, like Moses, intercedes for his people,

who, like those slain by Phinehas, dies on behalf of a guilty party,

and who, like the high priest, takes away the iniquity of others.

and who, like the high priest, takes away the iniquity of others.

At the same time, the sacrifice offered by Isaiah 53’s servant differs from, and surpasses, those mentioned above in a number of important respects.

Unlike Moses’s, it is not merely offered, but is accepted; indeed, it is borne of YHWH’s initiative.

Unlike Phinehas’s victims’, it is a righteous sacrifice, and is offered voluntarily.

Unlike Phinehas’s victims’, it is a righteous sacrifice, and is offered voluntarily.

And, unlike the high priest’s, it does not signal the end of a priesthood, but the inauguration of a new one, since, after the servant’s life has been accepted as a sacrifice for sin, YHWH prolongs his servant’s days.

Consider, then, the four principles/strands-of-thought outlined above:

🔹 While the forgiveness of sin affirms YHWH’s faithfulness to his covenant and to his nature as ‘merciful and gracious’ (Exod. 34.6), it casts doubt on his truthfulness. (Does sin lead to death or not?)

🔹 While the forgiveness of sin affirms YHWH’s faithfulness to his covenant and to his nature as ‘merciful and gracious’ (Exod. 34.6), it casts doubt on his truthfulness. (Does sin lead to death or not?)

🔹 Sacrifices for sin, however, affirm both YHWH’s faithfulness and his truthfulness.

🔹 Although Israel’s sacrificial system provides atonement, it does so in a very limited way, and Ezekiel anticipates a better system to come.

🔹 Although Israel’s sacrificial system provides atonement, it does so in a very limited way, and Ezekiel anticipates a better system to come.

🔹 And human life has a power to atone which animal life lacks.

Against the backdrop of these principles, the narrative of the New Testament unfolds, and introduces us to YHWH’s appointed Messiah, Jesus—a greater than Jonah, a greater than Moses, and a great than Ezekiel’s temple:

one whose origins (like those of Ezekiel’s temple) do not involve human hands;

one who is holy and untainted by creation’s curse;

one from whose side fresh water flows forth (as it does from Ezekiel’s temple) to a thirsty creation;

one who is holy and untainted by creation’s curse;

one from whose side fresh water flows forth (as it does from Ezekiel’s temple) to a thirsty creation;

one who is certified as without blemish by Pontius Pilate and slain at the time of the Passover;

one who descends to the heart of the earth (like Jonah) in order to assuage YHWH’s anger, where YHWH’s ‘waves’ of anger pass over him—, and who arises from the deep three days later;

one who descends to the heart of the earth (like Jonah) in order to assuage YHWH’s anger, where YHWH’s ‘waves’ of anger pass over him—, and who arises from the deep three days later;

one whose message is not heeded by his own people yet embraced among the Gentiles;

one who ascends into YHWH’s presence (like Moses) in order to atone for his people’s sins, where he can legitimately represent not only Israel but all creation (since he is the ruler of creation);

one who ascends into YHWH’s presence (like Moses) in order to atone for his people’s sins, where he can legitimately represent not only Israel but all creation (since he is the ruler of creation);

one who comes to forgive his people’s sins in faithfulness to YHWH’s covenant;

and one who will one day return to judge the whole world in truth.

and one who will one day return to judge the whole world in truth.

YHWH has ultimately, therefore, chosen to uphold his faithfulness and truth, not by means of an argument or statement, nor at the expense of animal life (about which he is deeply concerned: 4.12),

but by means of a person: his own beloved Son.

but by means of a person: his own beloved Son.

And, as a result, YHWH can deal with people exactly as he pleases.

He can deal with people in mercy—that is to say, he can forgive their transgressions—, or he can deal with them in truth—that is to say, he can repay people in accord with what their deeds deserve.

He can deal with people in mercy—that is to say, he can forgive their transgressions—, or he can deal with them in truth—that is to say, he can repay people in accord with what their deeds deserve.

As the book of Jonah draws to its close, however, Jonah doesn’t seem happy to grant YHWH such freedom,

since he thinks YHWH is a soft touch.

since he thinks YHWH is a soft touch.

As we’ve seen, Jonah has no right to complain about YHWH’s dispensation of mercy to Nineveh, not least because, had YHWH not extended similar mercy to Israel, Jonah would be in the same position as the Ninevites himself.

And so YHWH gives Jonah an object lesson to remind him of that fact.

As Jonah sits outside Nineveh, beneath a shelter he’s made for himself, YHWH provides Jonah with a *second* shelter—a plant of some kind (קיקיון).

The plant is clearly superior to Jonah’s self-made shelter, since it’s said to ‘save’ (להציל) Jonah from his ‘evil’ plight (רעה).

The plant is clearly superior to Jonah’s self-made shelter, since it’s said to ‘save’ (להציל) Jonah from his ‘evil’ plight (רעה).

It doesn’t, however, last very long. YHWH sends a worm to ‘slay’ (להכות) the shelter, which causes the sun to beat down on Jonah’s head and, as a result, Jonah despairs of life.

The text of 4.5–8 thus describes an odd state of affairs (which many commentators have rectified by means of textual surgery), with Jonah seated happily beneath two shelters, one of which is his own handiwork and the other of which is YHWH’s.

Why? What does YHWH want Jonah to learn from these two shelters?

The answer, I suggest, is as follows: YHWH wants to Jonah to learn what it’s like to live in a world where people invariably get what they deserve.

The answer, I suggest, is as follows: YHWH wants to Jonah to learn what it’s like to live in a world where people invariably get what they deserve.

Jonah’s self-made shelter is the world he deserves—a shelter created by his own deeds/efforts, a world of ‘truth’ (אמת), as it were.

Meanwhile, the shelter with which YHWH has provided Jonah is a world of ‘mercy’ and ‘faithfulness’ (חסד)—a world characterised by ‘salvation’ (להציל) (such as the Ninevites have enjoyed), a world far better than Jonah deserves.

And, when YHWH returns Jonah to his old (self-constructed) world of ‘truth’, he realises he doesn’t like it very much.

It’s not the kind of world Jonah wants to live in.

It’s not the kind of world Jonah wants to live in.

Hence, before he condemns the Ninevites to a world of unmitigated truth/justice’, Jonah should think very carefully about what such a world might mean for him.

-- A FINAL REFLECTION --

Jonah’s story is now roughly 2,700 years old, but it has aged remarkably well.

Jonah’s story is now roughly 2,700 years old, but it has aged remarkably well.

Many people today seem to want to turn the present world into a world which is entirely devoid of mercy and forgiveness—a world where people ‘get their comeuppance’ (as some men count ‘comeuppance’), a world without second chances, a world without any hope of redemption.

Such people would do well to read the book of Jonah and think carefully about what their utopia might mean for them,

not to mention how the afterlife might pan out if God is of the same mindset.

THE END.

P.S. Gluttons for punishment can access the whole thread/note here:

academia.edu/44638365/

THE END.

P.S. Gluttons for punishment can access the whole thread/note here:

academia.edu/44638365/

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh