#HistoryKeThread: Mwangeka’s Blood

This first pic is of a view taken from high up in the Taita Hills.

This first pic is of a view taken from high up in the Taita Hills.

In the late 19th century, Mekatilili’s Giriama were not the only community from present-day Coast province that rose against imposition of white rule by gun-toting Europeans. The Taita of Mwanda, too, did.

At that time, the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC) was the vessel through which Britain asserted its dominion over what would later become Kenya.

Incorporated in 1888 and chartered later the same year by the Queen of England, IBEAC was specially created to promote trade activities in territories under the control of the British.

So in the 1890s, IBEAC stepped up plans to open up the interior of East Africa by setting up administrative structures and laying down infrastructure, such as ox-cart roads (that later formed part of Nairobi-Mombasa highway that we know of today).

To IBEAC officials led by William Mackinnon (pictured), the perilous and unpredictable nature of the interior of East Africa compelled its officers to bear arms. Indeed, some of its officials, such as one Captain Robert Nelson, had military experience.

The mandate of the IBEAC, which also played a key role in the growth and expansion of Christian missions deeper in the hinterland, was to open up the interior for trade.

Of course, we are not talking about trade among African communities. We are talking about trade promoted by Europeans.

Africans were against certain forms of trade, such as slave trade. They were also opposed to imposition of taxes, e.g. hut tax.

On the other hand, Arabs played a leading role in the trafficking and trading of slaves. But as trade in slavery faded away, Arabs stepped up on other forms of trade, such as in cloth, mirrors, cowrie shells and ivory.

Some community leaders such as Mwangeka Malowa of the Taita took advantage of the blossoming trade by providing security to trade caravans in exchange for goodies. If a caravan was not “recognized”, it was attacked by his warriors.

Indeed, in 1890 an IBEAC official described Taita as an area of “hill robbers, sitting on their mountains like hawks, or barons of old, watching for any weak party coming near their homes...”

Obviously, IBEAC were opposed to what the Taita leader was doing. And an incident that took place in Taita territory gave IBEAC good reason to finally confront the chief and his warriors.

So what actually happened?

In 1892, Taita warriors from Mwanda, acting on orders from Mwangeka, raided the caravan of a cloth trader called Mohamed bin Ali. The trader had left his overnight camp near Bura when he was attacked.

The Taita were wise not to defy any instructions from their Chief, who reportedly had a massive frame and was a formidable warrior in his youth. He was also said to possess medicinal powers “that repelled arrows and the white man’s bullets”.

In the 1950s, elders from nearby Mbale remembered the chief as someone who was not only physically strong but also had the natural aura of a leader.

In the Mohamed bin Ali incident, it is recorded that the Taita raiders had dressed themselves like Maasai warriors. I presume this ingenuity was designed to deflect any suspicion or blame for the attack away from the actual culprits.

Other reports say that the raid was meant to be a joint attack by Mwangeka’s subjects and those of a leader from Bura. But perhaps fearing repercussions, the Bura chief reportedly balked at the idea. And so Mwangeka and his warriors carried out the raid on their own.

In the aftermath of the attack, the warriors grabbed the caravan loot and disappeared with it into the depths of Taita Hills.

Mohammed however survived the raid and fled on foot to Mombasa, where he reported the raid to IBEAC officials.

Mohammed however survived the raid and fled on foot to Mombasa, where he reported the raid to IBEAC officials.

He wasn’t fooled by the Taita warriors’ attempted camouflage. He told officials that he was certain the raiders were not Maasai, and that they were from Bura, which is situated in Mwatate division today.

It was then that Captain Nelson of the IBEAC was asked to lead a column of Company soldiers to exact punishment on the raiders.

When the punitive mission reached Taita Hills, indignant Bura elders denied culpability and pointed fingers at Mwangeka and a rival warrior group from Mwanda.

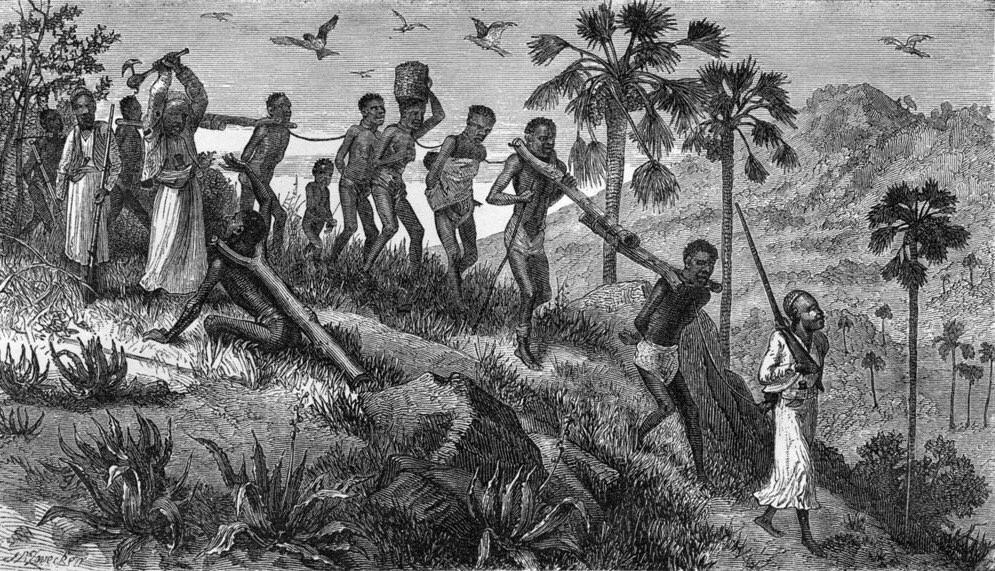

So Capt. Nelson led his soldiers to the Bura-Mwanda border, where a column of Mwangeka’s warriors lurking behind shrubs set upon the soldiers with bows and arrows (pic for illustration only).

The power of the European gun was too strong for the warriors’ arrows. A number of Mwangeka’s warriors were killed. Capt. Nelson and his men burned several villages and drove away towards Bura as many goats and sheep as they could manage.

Capt. Nelson took his troops to the home of a collaborating Bura elder for the night, oblivious of the fact that Mwangeka’s warriors had stalked them. The warriors had been made to believe that they were invincible against bullets.

So later that night, war cries rent the air and Company soldiers found themselves under attack. After a battle that lasted half an hour, rifles again overwhelmed arrows and spears. Capt. Nelson lost 2 men with 12 wounded. Scores of warriors, including Mwangeka himself, lay dead.

The following morning, the wider Taita country woke up to incredulous news of Mwangeka’s defeat.

That a force of outsiders unfamiliar with the treacherous Taita Hills had defeated Mwangeka and his medicine gained the white man respect among the Taita.

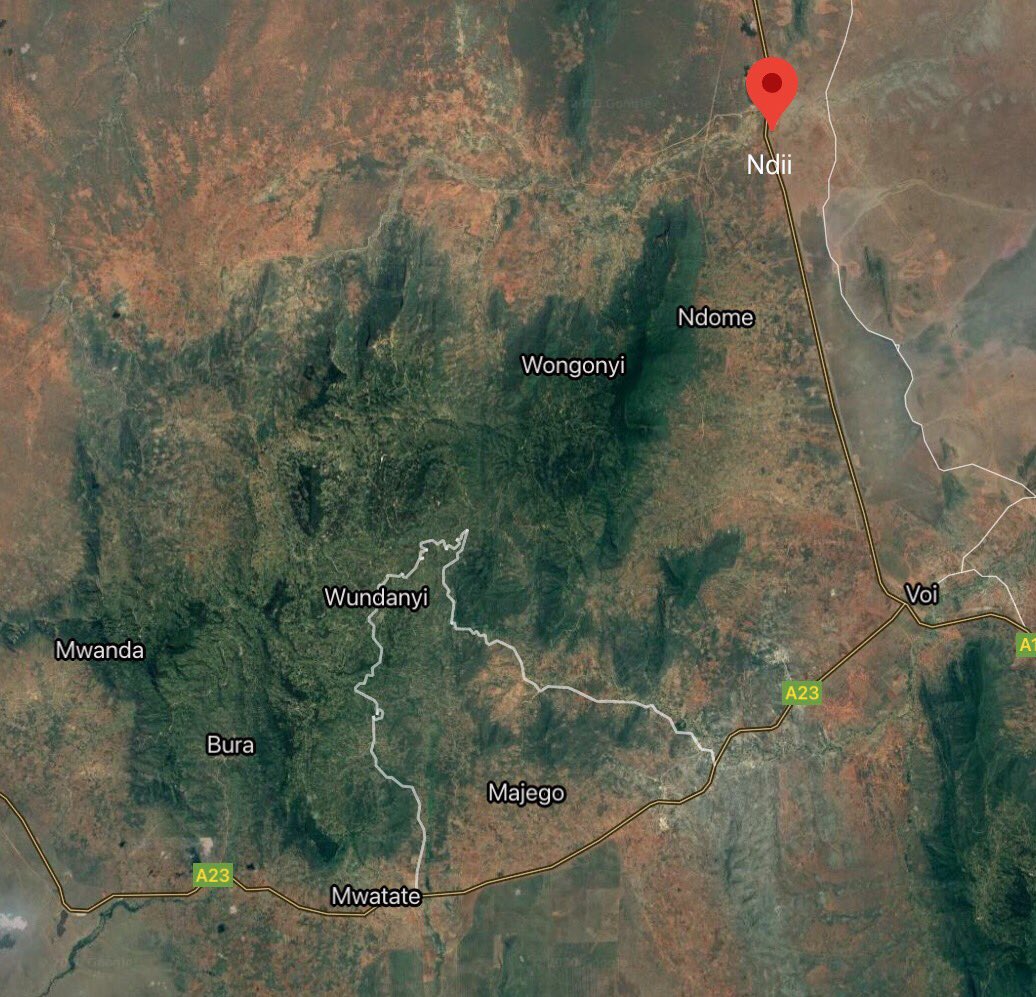

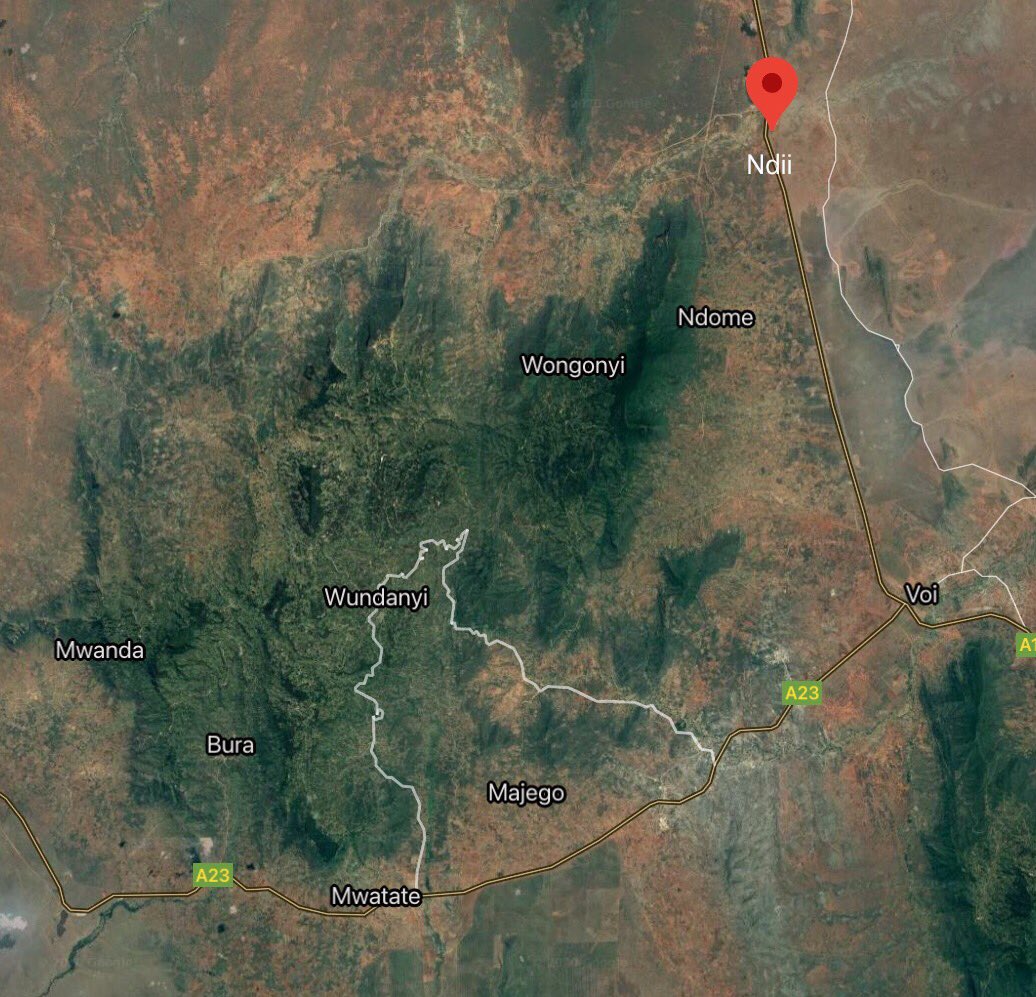

Following the resistance, the IBEAC put up a military station at Ndii, which a few years later also served as one of the stations for the Uganda Railway.

There is little doubt that Mwangeka was charismatic. But how he arguably failed to employ his charisma to marshal the entire Taita community against IBEAC is puzzling.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh