#HistoryKeThread: Succeeding Kenyatta

In the second half the 1970s, Mzee’s health began to deteriorate.

In the second half the 1970s, Mzee’s health began to deteriorate.

Thus the matter of his succession took centre stage.

There emerged a group of powerful individuals who, opposed to Vice President Daniel arap Moi taking over the reins of leadership from President Jomo Kenyatta, called on the Constitution to be amended.

There emerged a group of powerful individuals who, opposed to Vice President Daniel arap Moi taking over the reins of leadership from President Jomo Kenyatta, called on the Constitution to be amended.

The media referred to the clamour by this group, which comprised of powerful leaders from Kiambu, as the Change-The-Constitution movement.

Prominent politicians like Cabinet Ministers Mbiyu Koinange, Dr. Njoroge Mungai and James Gichuru - together with others from Kiambu, collectively christened the Kiambu Mafia, were seen as leaders of this Movement.

The group sought a constitutional change in which the Speaker of National Assembly would instead be sworn in as President. They fronted cabinet minister Dr. Njoroge Mungai for the Speaker’s post.

From 1976, concerns were raised about the nature of advanced paramilitary training that the Anti-Stock Theft Unit, a new division of the police force, underwent.

The training included parachute drops, usually a preserve of the military.

The training included parachute drops, usually a preserve of the military.

There were allegations that members of the Unit, known better by their moniker “Ngorokos”, were being trained to carry out a series of assassinations.

They were under the direct command of Assistant Police Commissioner and Rift Valley police boss James Erastus Mungai (as Rift Valley police boss, he was asked to constitute the Anti-Stock Theft Unit).

The plot to carry out assassinations targeted government officials considered allies of Vice President Daniel arap Moi, it was alleged. Some even went further and claimed that VP Moi himself was the primary target.

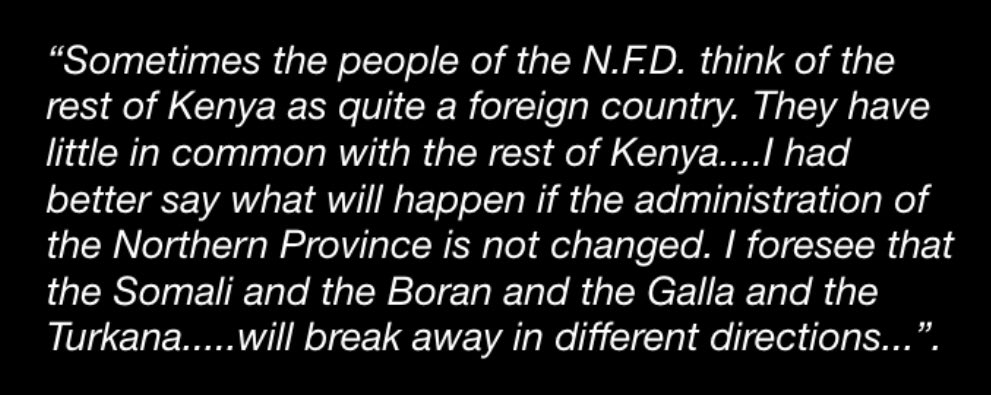

With succession talk taking over national headlines, Attorney General Charles Njonjo on 6th October 1976 warned that it was a criminal offense “punishable by death for anyone to imagine, devise or intend the death or deposition of the president.” nytimes.com/1976/10/11/arc…

Inexplicably, a statement he issued later was revised to read that the offense was punishable by a mandatory life imprisonment.

This declaration by Njonjo (pictured) came at a time when there were rumors that Mzee was too ill to govern the country, and that he was being isolated from government affairs.

Some observers pointed out that major administrative decisions were being made by state officials close to Mzee Kenyatta. Fingers were pointed at powerful cabinet minister Mbiyu Koinange as the person who made those decisions.

Others claimed Njonjo was the one isolating President Kenyatta in running affairs of the government.

To the relief of Moi’s supporters (and maybe Njonjo’s), State House issued a terse statement days after Njonjo’s public warning:

“The government reiterates its earlier statement by the Attorney General”.

“The government reiterates its earlier statement by the Attorney General”.

In spite of the message from State House, the Change-The-Constitution gang at various rallies continued campaigning for the Constitution to be amended.

Determined to ensure that there was no power vacuum, and that Kenyatta’s succession was meticulously handled in line with the Constitution, AG Charles Njonjo, Special Branch Head James Kanyotu and Chief Secretary Geoffrey Kariithi took charge of affairs.

They asked the Vice President and, constitutionally, the President-designate to quickly travel to Nairobi to be sworn in as Acting President.

The Kiambu Mafia must have tipped off their ally James Mungai, the Rift Valley police boss. Mungai was asked to stop Moi from traveling to Nairobi. Several roadblocks on roads leading to Nairobi were mounted.

But it was too late; Moi’s convoy was nearing the city by the time roadblocks were mounted.

A few months later, on 26th October 1978, Njonjo informed a stunned Parliament that “a certain group” had planned assassinations that were designed to stop President Moi’s ascendancy.

A few months later, on 26th October 1978, Njonjo informed a stunned Parliament that “a certain group” had planned assassinations that were designed to stop President Moi’s ascendancy.

Citing intelligence reports, Njonjo said that there was a list of targets for the assassination that included him. Others on the list were Moi and his VP, Kibaki.

Had Mzee died in Nakuru, Njonjo told Parliament, those on the list would have been summoned and then killed “before the rest of the country could determine what had happened...”

Njonjo implicated Police Commissioner Bernard Hinga (pictured), his deputy, Nene, and Asst. Commissioner James Mungai.

Following the revelations, Mungai was suspended while his superiors Hinga and Nene resigned. The Ngorokos unit was disbanded and its members absorbed into the General Service Unit (GSU) of the police force. nytimes.com/1978/11/20/arc…

Fearing for his life, Mungai later fled to Switzerland via Sudan. It was days before the government discovered that Mungai had fled the country. A warrant of arrest was issued against him for “embezzlement”.

He returned a few months later (pictured, in suit) following guarantees that he would not be persecuted.

However, weeks after his return, as the Daily Nation reported, the Mungai saga was declared a closed matter and he was not persecuted.

Image credits: Daily Nation, Getty Images.

Called for*

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh