1. What happened to EU27 emissions in 2020 & what does it mean for the 55% 2030 target?

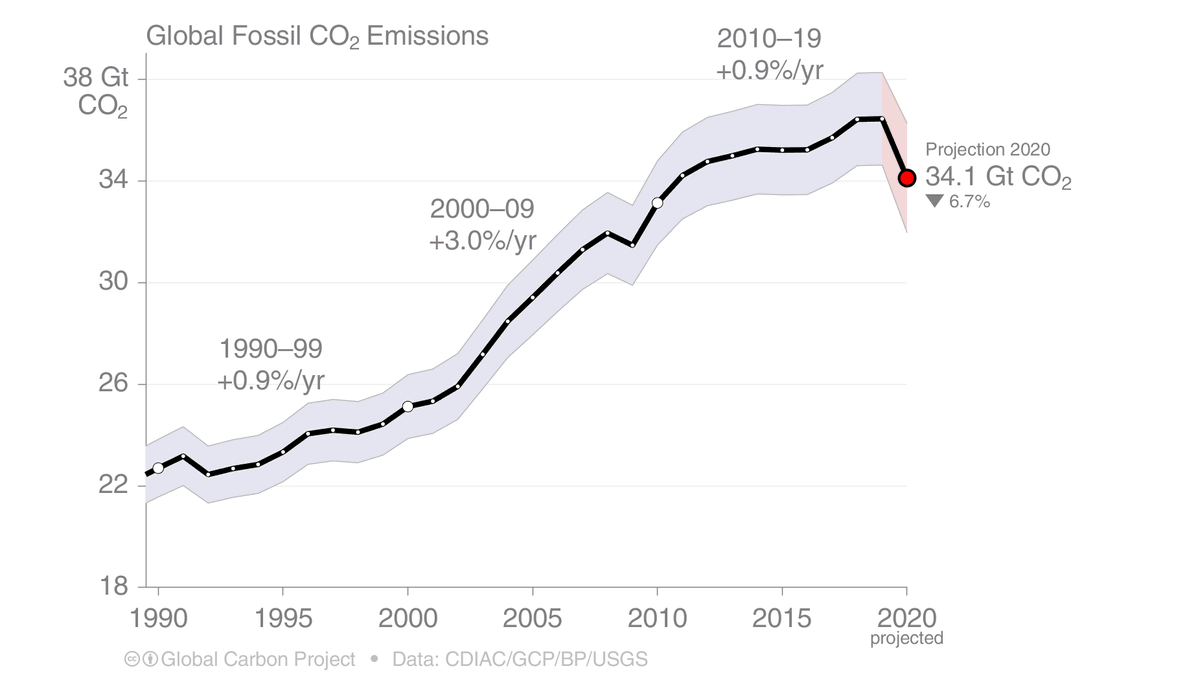

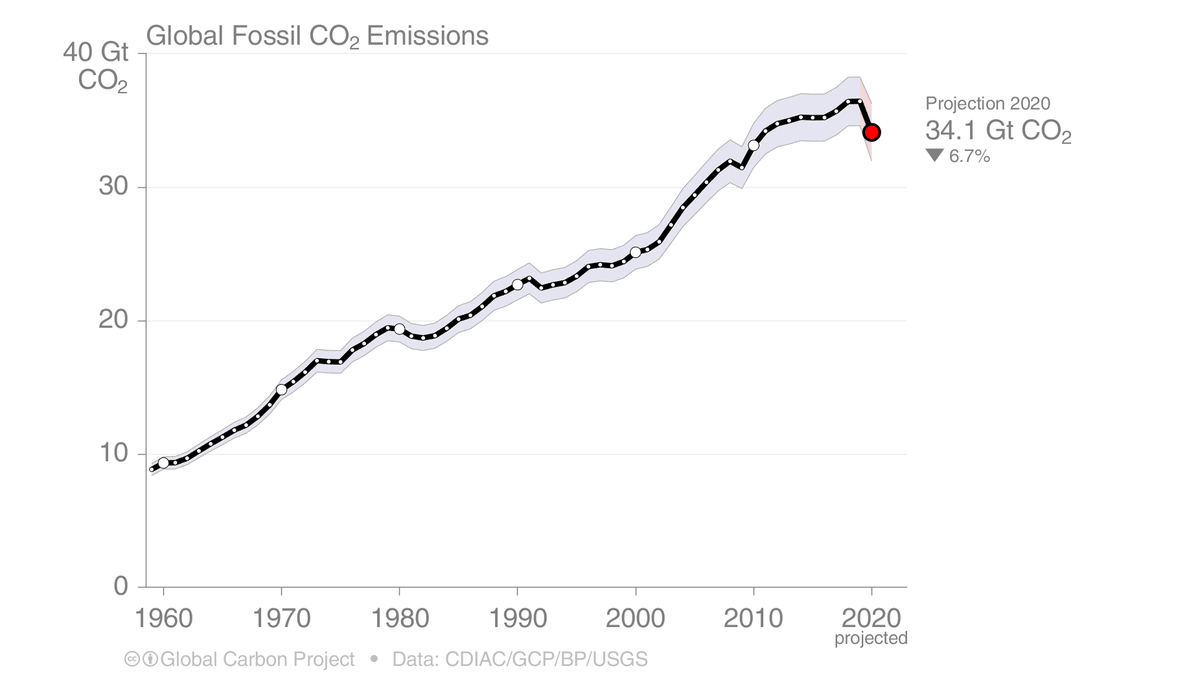

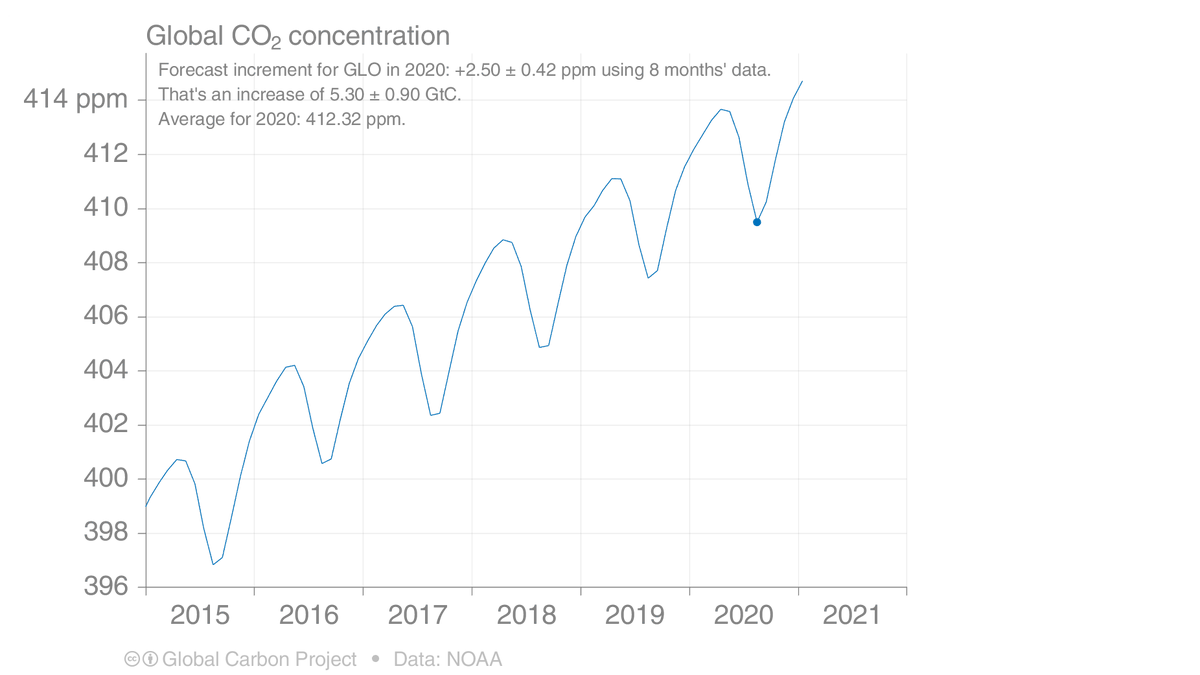

COVID19 sent CO₂ emissions down ~12%:

* Coal went down 18% in 2019, COVID cements this in

* Oil has grown last 5 years, 2020 needs to start a new decline

* Gas is stubborn, problem for 2030!

COVID19 sent CO₂ emissions down ~12%:

* Coal went down 18% in 2019, COVID cements this in

* Oil has grown last 5 years, 2020 needs to start a new decline

* Gas is stubborn, problem for 2030!

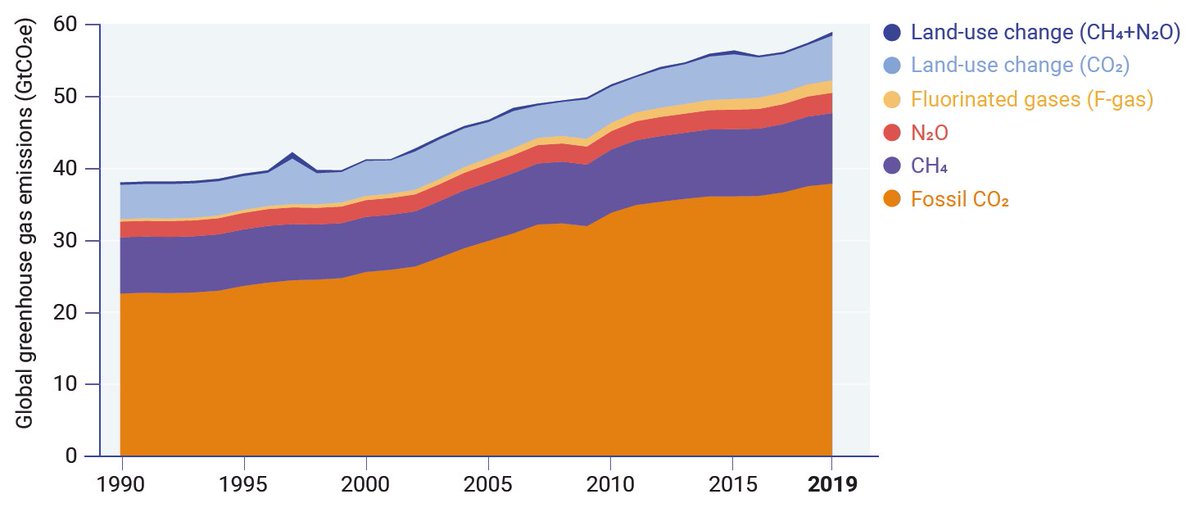

2. The EU target is for GHGs (not just CO₂), but now includes the forest sink.

The inclusion of the sink makes the relative reduction in emissions from 1990 larger (24% to 2018) & makes a 2030 target easier to achieve (in terms of reduced growth rates to achieve it).

But...

The inclusion of the sink makes the relative reduction in emissions from 1990 larger (24% to 2018) & makes a 2030 target easier to achieve (in terms of reduced growth rates to achieve it).

But...

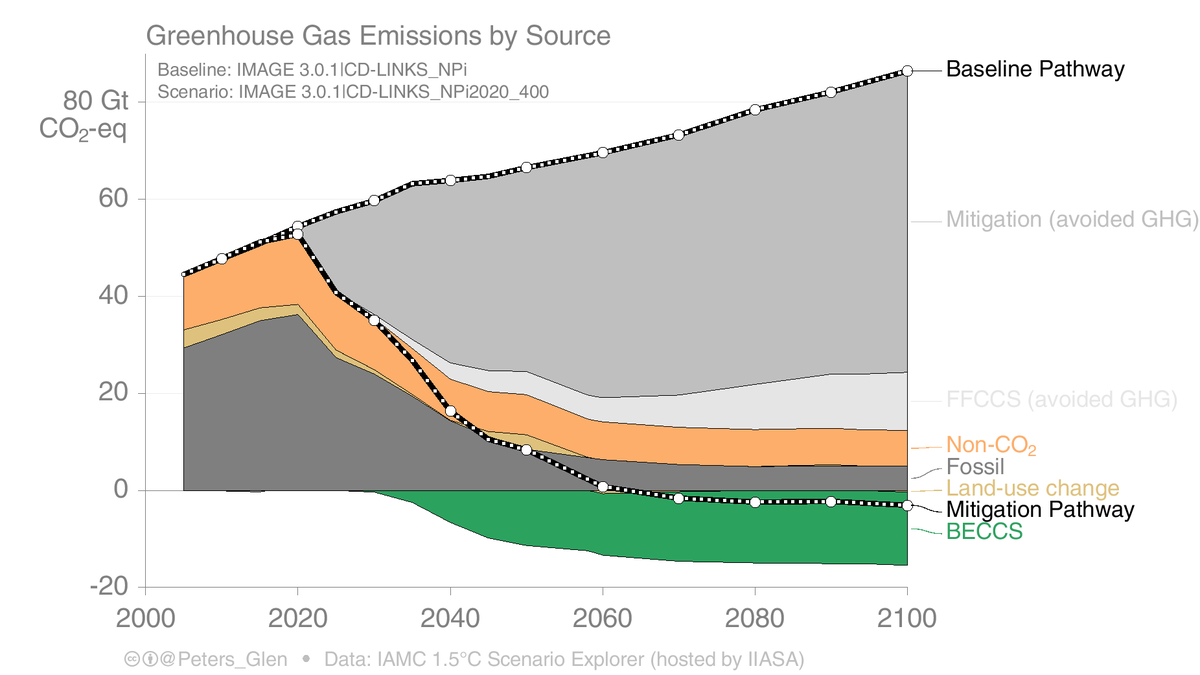

3. The inclusion of the land sink is probably necessarily to meet the 2050 net-zero GHG emission goal.

It may be hard to maintain the land sink, particularly in the face of climate change.

The alternative is using technical carbon removal (BECCS or DACCS, which have troubles).

It may be hard to maintain the land sink, particularly in the face of climate change.

The alternative is using technical carbon removal (BECCS or DACCS, which have troubles).

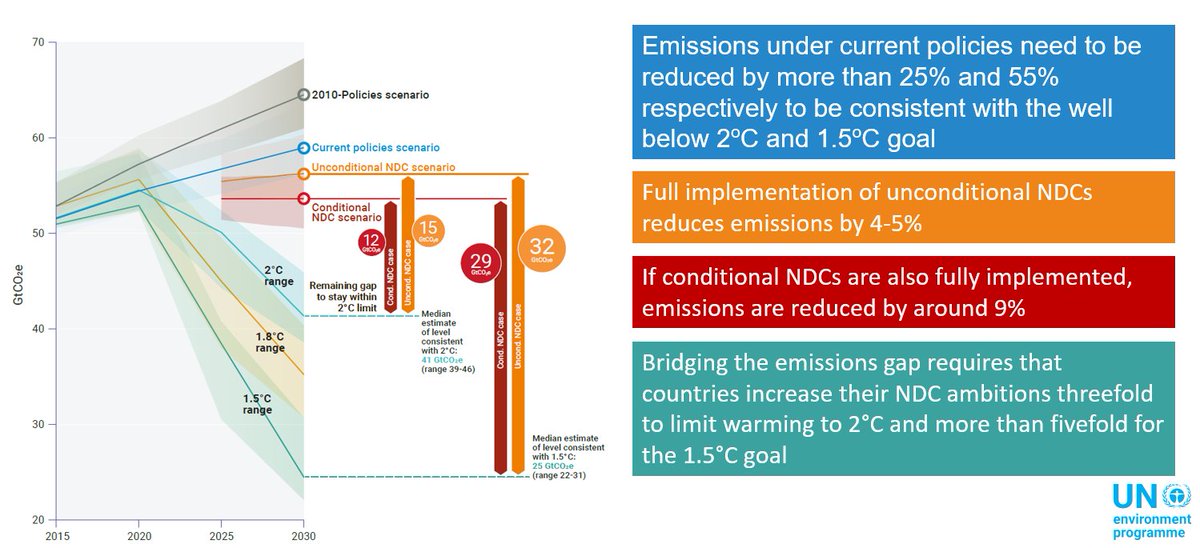

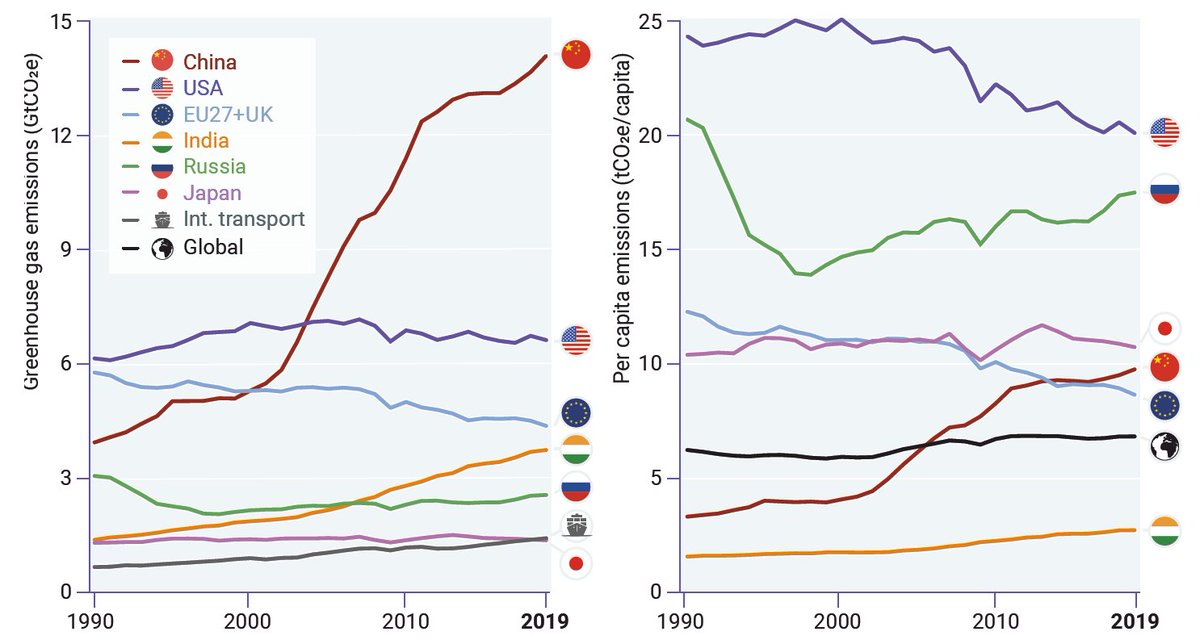

4. Overall, the EU is well set to meet (& beat) the 2030 target.

* Changes are happening in the energy sector, with a rising EU-ETS price.

* The challenges will be reigning in transport emissions (oil) & turning the corner on gas.

* Changes are happening in the energy sector, with a rising EU-ETS price.

* The challenges will be reigning in transport emissions (oil) & turning the corner on gas.

5. The EU has already beaten its 2020 target, & may well make the 2030 target in a canter without using carry over credits (for those that know @ScottMorrisonMP's antics).

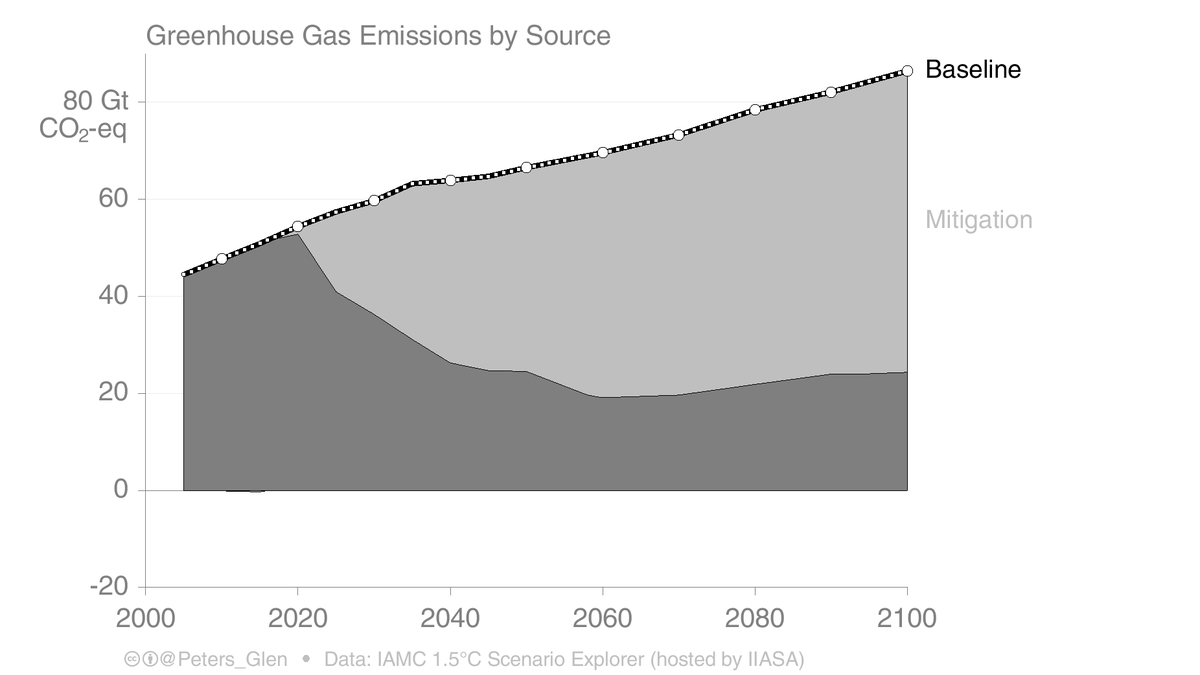

This means the EU has the potential to beat & up its 2030 target, which is necessary for <1.5°C.

/end

This means the EU has the potential to beat & up its 2030 target, which is necessary for <1.5°C.

/end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh