A few quick thoughts on China reportedly making the unofficial ban on Australian coal imports official:

theguardian.com/australia-news…

theguardian.com/australia-news…

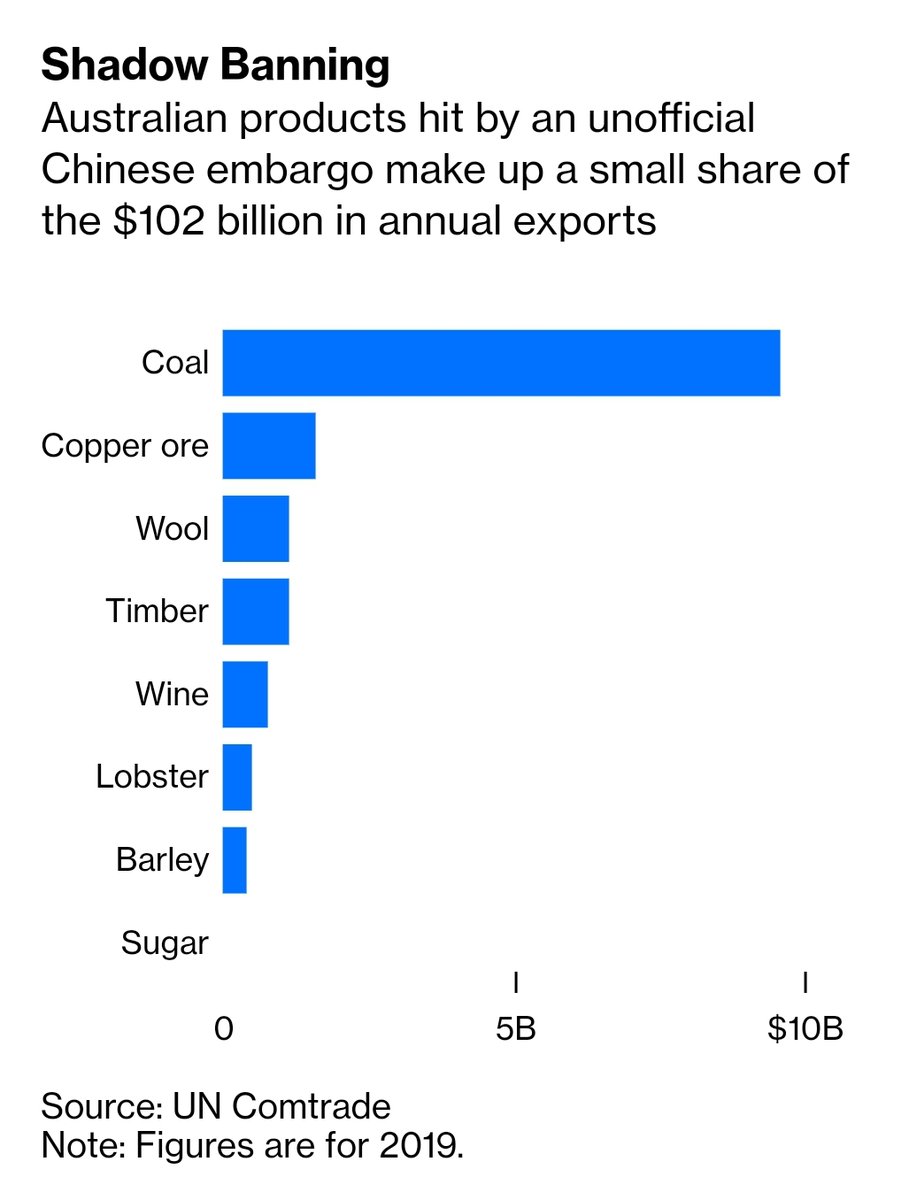

This is the big one. Wine and lobster get the headlines, but coal makes up nearly 2/3 of the export value of the products on China's naughty list:

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

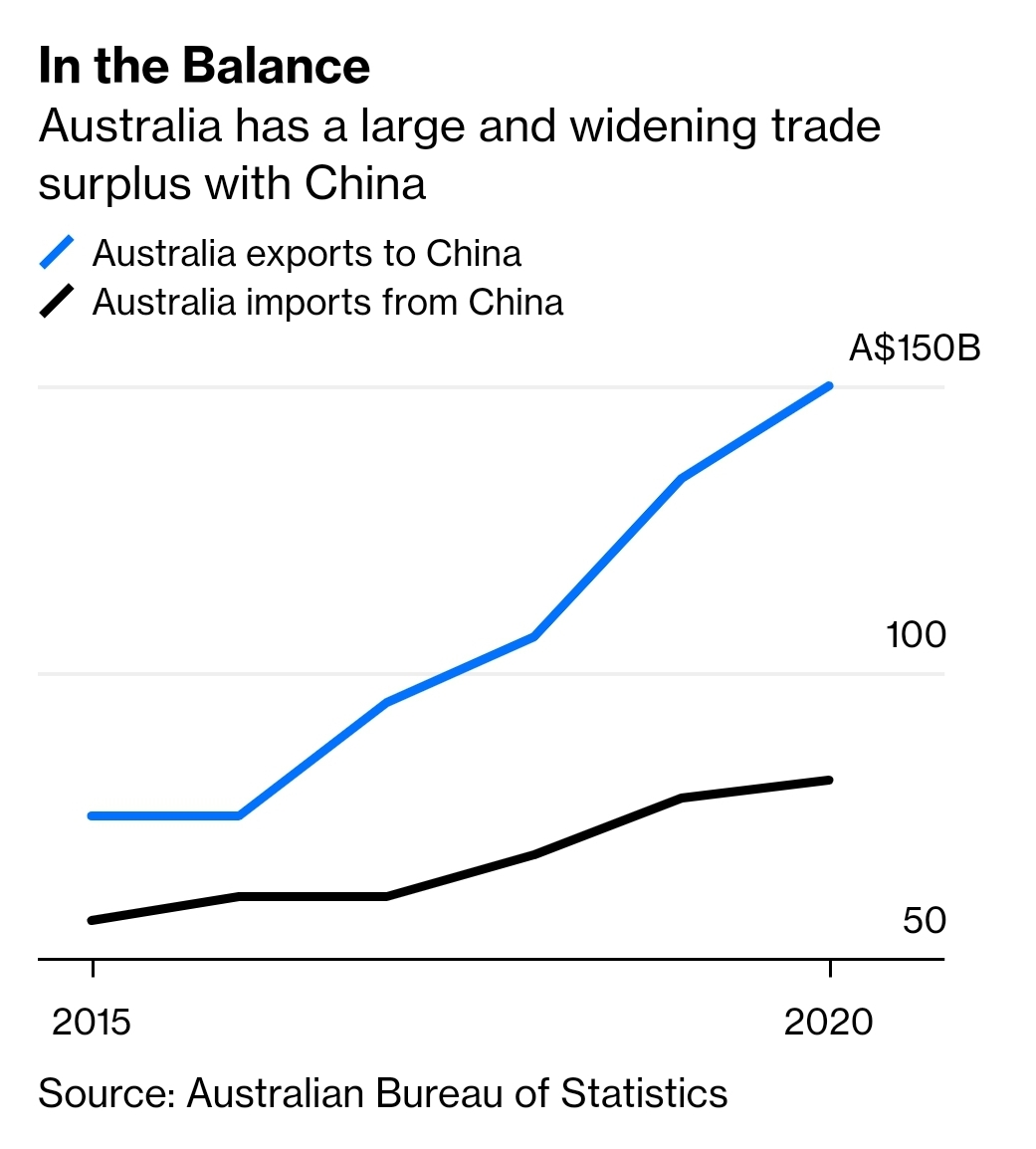

For all the bad blood in the Australia-China relationship ober the past six years, trade has boomed. The 2020 fiscal year was the fifth consecutive record year for Aus->China exports and I suspect 2021 may go higher still.

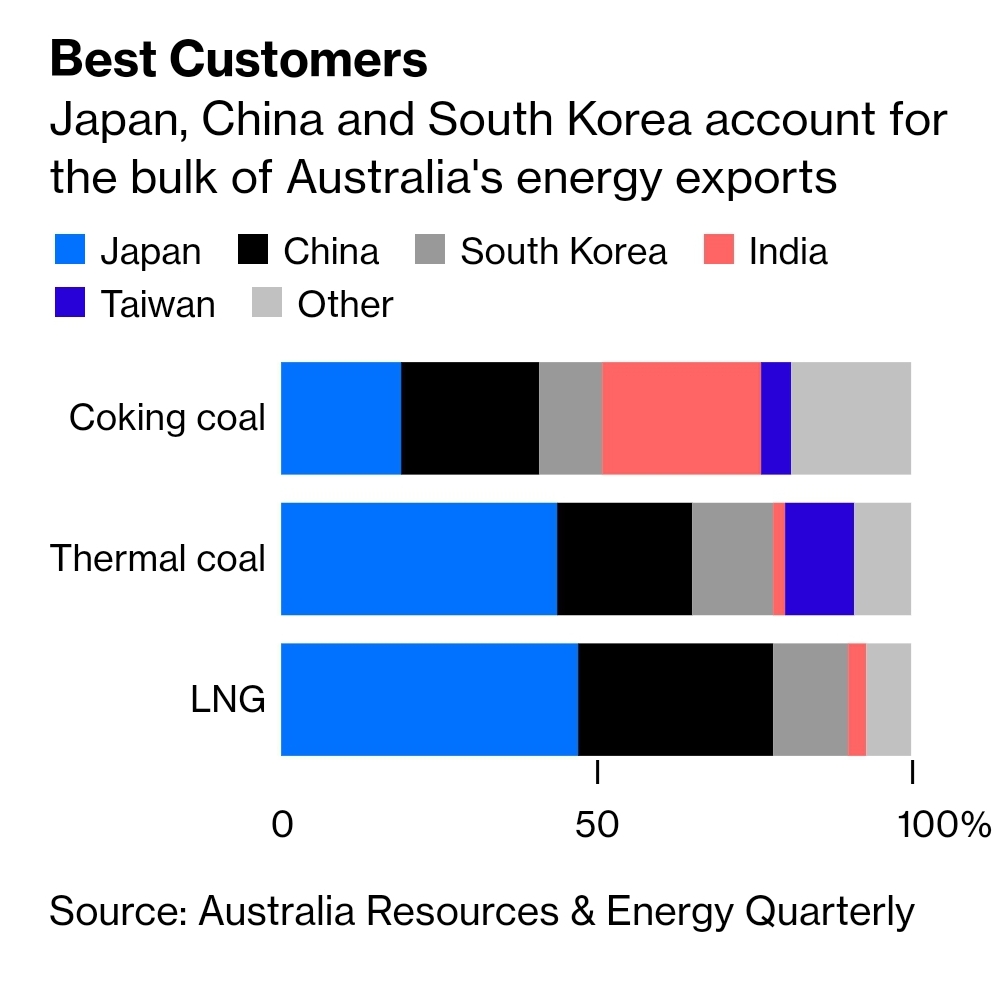

China isn't the only game in town for Australian coal exports. As a trade partner for fossil fuels it's a bit below Japan and on a par with South Korea, Taiwan and India:

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

At the same time, miners aren't going to find it easy to get alternative buyers. Power stations and steel mills are fussy about the coal grade they use.

They also can't suddenly generate more power or make more steel just because Australia has a ship going begging.

They also can't suddenly generate more power or make more steel just because Australia has a ship going begging.

I still suspect this ban will get relaxed. Chinese utilities like imported coal because it costs less than comparable domestic grades, and their margins are pressured because the power market is being liberalised and they're being undercut by renewables.

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

China is also very short of coke for steelmaking, and the steel industry is going gangbusters at present. China is 95% self-sufficient in coal overall, but doing without Australian coking coal in the near term will be hard.

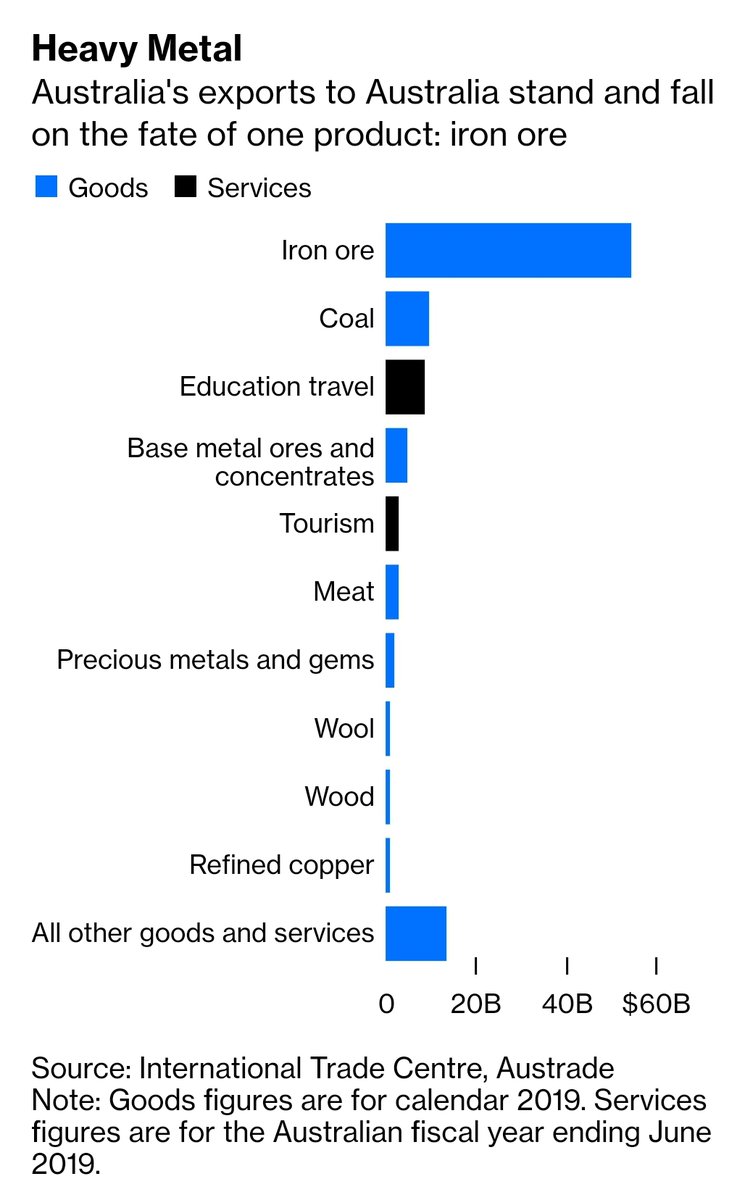

There's some people wondering what happens if China does the same to Australian iron ore. I don't think that's at all credible as a short term measure.

About 1/3 of Chinese steel is made from Australian ore and China is still hooked on a sclerotic steel-led development model.

About 1/3 of Chinese steel is made from Australian ore and China is still hooked on a sclerotic steel-led development model.

Reducing steel production by 1/3 is what happened in Europe and America during the Great Depression. Beijing is not going to take that scale of risk with its domestic economy, even for the sake of punishing Canberra.

For Australia this should be, pardon the pun, a canary-in-the-coal-mine moment.

I think in the short term exports will probably be OK as the wider Australian-coal-consuming north Asian economy recovers from coronavirus.

I think in the short term exports will probably be OK as the wider Australian-coal-consuming north Asian economy recovers from coronavirus.

But in the long term We Know This Industry Is Dying, even if the political class in Australia refuse to face up to it.

Korea and Japan both have 2050 net zero targets, China has one for 2060.

The decline could be much faster than Australians are expecting.

Korea and Japan both have 2050 net zero targets, China has one for 2060.

The decline could be much faster than Australians are expecting.

Even Glencore, the biggest exporter of Australian coal, this month announced a 2050 net zero target:

glencore.com/media-and-insi…

glencore.com/media-and-insi…

The countries in South and Southeast Asia that were once hailed as the future saviours of the seaborne coal market (Vietnam, Bangladesh, Thailand, the Philippines, Pakistan) are cutting back because renewables are cheaper and don't poison their citizens.

While China and India may persist longer, their politicians are as obsessed with "protecting coal jobs" as Australian ones are. India plans to halt imports by 2024 as a matter of official policy.

Ironically, the thing that China could do that would *really* hurt Australia is also the thing that would be best for its own economy: Give up on the model of industrial-driven growth of the past decade and shift to being a more consumer-oriented middle-income economy.

China consumes *far* more steel per unit of GDP than pretty much any country in history. For Beijing, it's a switch they can flip to get the economy roaring. For Canberra, the iron ore used is the basis of a entire country's exports.

China's power sector will decarbonize over the coming years but one of the quickest things it could do to move towards net zero would be to start consuming steel like a normal country.

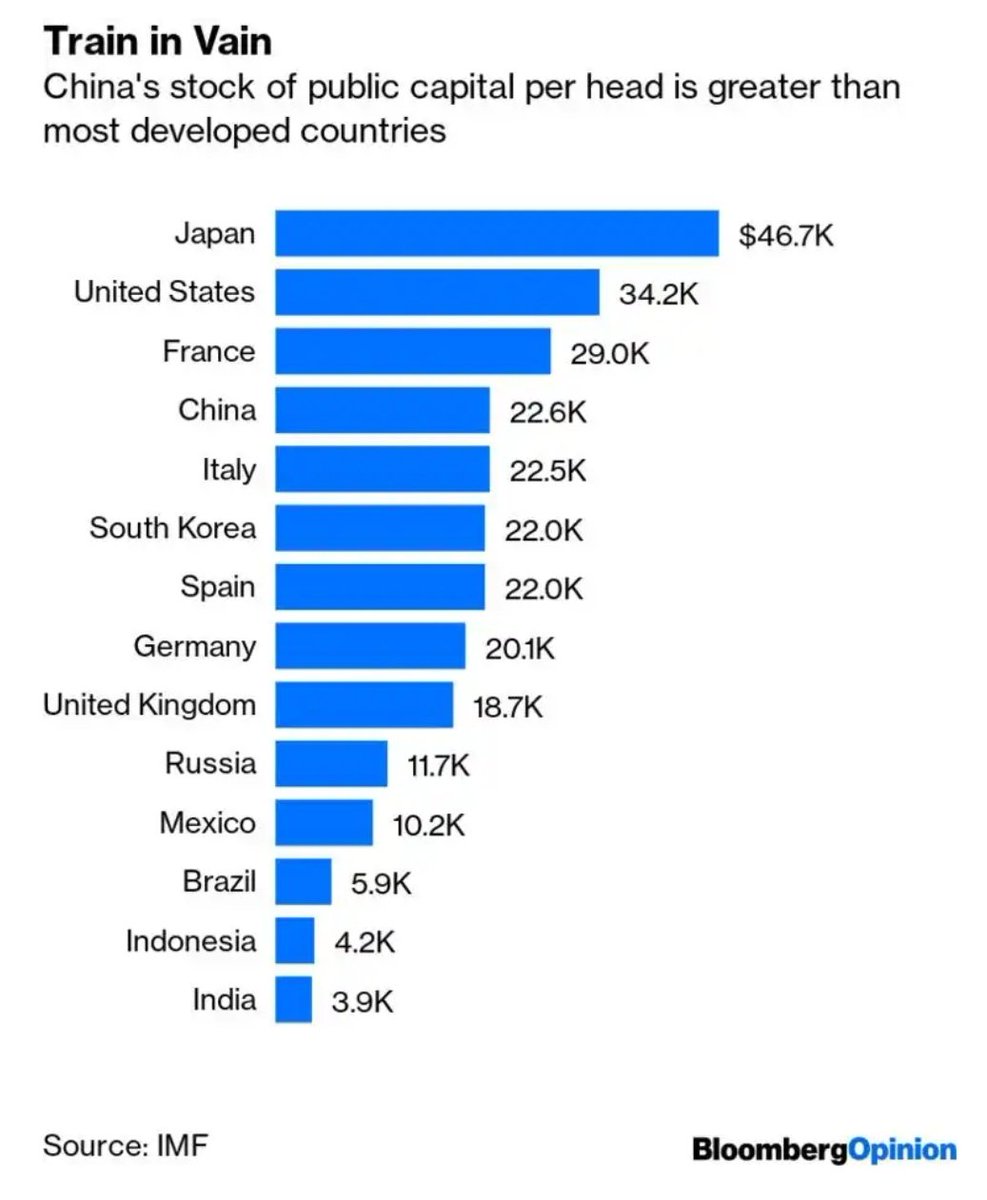

China already has a larger public capital stock per head than Germany, South Korea or the UK. It doesn't need more boondoggle bridges, housing developments and concert halls. Debt-to-GDP remains the highest of any major emerging economy.

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

Switching to a consumption-based growth model, rather than firing up fixed asset investment every time the economy looks weak, is the only way China can achieve its ambition of developed-economy status by 2035.

But that looks less likely than ever at the moment, so I expect China and Australia will remain locked in this dysfunctional relationship for a while longer. (ends)

wsj.com/articles/china…

wsj.com/articles/china…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh