8: Colonial Rule in West Africa

wasscehistorytextbook.com/8-colonial-rul…

History Textbook

West African Senior School Certificate Examination

(1/6 continue)

The European scramble for Africa culminated in the Berlin West African Conference of 1884-85.

wasscehistorytextbook.com/8-colonial-rul…

History Textbook

West African Senior School Certificate Examination

(1/6 continue)

The European scramble for Africa culminated in the Berlin West African Conference of 1884-85.

The conference was called by German Chancellor Bismarck and would set up the parameters for the eventual partition of Africa.

European nations were summoned to discuss issues of free navigation along the Niger and Congo rivers and to settle new claims to African coasts.

European nations were summoned to discuss issues of free navigation along the Niger and Congo rivers and to settle new claims to African coasts.

In the end, the European powers signed The Berlin Act (Treaty).

This treaty set up rules for European occupation of African territories.

The treaty stated that any European claim to any part of Africa, would only be recognized if it was effectively occupied.

This treaty set up rules for European occupation of African territories.

The treaty stated that any European claim to any part of Africa, would only be recognized if it was effectively occupied.

The Berlin Conference therefore set the stage for the eventual European military invasion and conquest of African continent.

With the exception of Ethiopia and Liberia, the entire continent came under European colonial rule.

With the exception of Ethiopia and Liberia, the entire continent came under European colonial rule.

The major colonial powers were Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, and Portugal.

The story of West Africa after the Berlin Conference revolves around 5 major themes: the establishment of European colonies, the consolidation of political authority,

The story of West Africa after the Berlin Conference revolves around 5 major themes: the establishment of European colonies, the consolidation of political authority,

the development of the colonies through forced labor, the cultural and economic transformation of West Africa, and West African Resistance.

European Penetration and West African Resistance to Penetration

European Penetration and West African Resistance to Penetration

Effective Occupation was a clause in the Berlin Treaty which gave Europe a blank check to use military force to occupy West African territories.

1885-1914 were the years of European conquest and amalgamations of pre-colonial states and societies into new states.

1885-1914 were the years of European conquest and amalgamations of pre-colonial states and societies into new states.

European imperialists continued to pursue their earlier treaty making processes whereby West African territories became European protectorates.

Protectorates were a loaded pause before the eventual European military occupation of West Africa.

Protectorates were a loaded pause before the eventual European military occupation of West Africa.

Because protectorate treaties posed serious challenges to West African independence most West African rulers naturally rejected them.

West African rulers adopted numerous strategies to forestall European occupation including: recourse to diplomacy, alliance,

West African rulers adopted numerous strategies to forestall European occupation including: recourse to diplomacy, alliance,

and when all else failed, military confrontation.

Recourse to Diplomacy

The British found few people as difficult to subdue as the Asante of Ghana in their quest to build their West African colonial empire.

Recourse to Diplomacy

The British found few people as difficult to subdue as the Asante of Ghana in their quest to build their West African colonial empire.

The Asante Wars against the British, which began in 1805, lasted a hundred years.

Although outmatched by superior weaponry, the Asante kept the British army at bay for a short final period of independence.

Although outmatched by superior weaponry, the Asante kept the British army at bay for a short final period of independence.

To understand the Asante wars, one has to look at role of King Prempeh I, who firmly resolved not to submit to British protection.

When pressured in 1891 to sign a protection treaty which implied British control of Asante, Prempeh firmly and confidently rejected idea.

When pressured in 1891 to sign a protection treaty which implied British control of Asante, Prempeh firmly and confidently rejected idea.

Here are his words to the British envoy:

The suggestion that Asante in its present state should come and enjoy the protection of Her Majesty the Queen and Empress of India, is a matter of very serious consideration and I am happy to say we have arrived at this conclusion,

The suggestion that Asante in its present state should come and enjoy the protection of Her Majesty the Queen and Empress of India, is a matter of very serious consideration and I am happy to say we have arrived at this conclusion,

that my kingdom of Asante will never commit itself to any such policy. Asante must remain [independent] of old . . .

In 1897, King Prempeh was exiled, and the Asante were told that he would never be returned.

He was first taken to Elmina Castle. From there,

In 1897, King Prempeh was exiled, and the Asante were told that he would never be returned.

He was first taken to Elmina Castle. From there,

he was taken to the Seychelles Islands.

In 1899, in a further attempt to humiliate the Asante people, the British sent British governor Sir Frederick Hodgson to Kumasi to demand the Golden Stool.

The Golden Stool was a symbol of Asante unity.

In 1899, in a further attempt to humiliate the Asante people, the British sent British governor Sir Frederick Hodgson to Kumasi to demand the Golden Stool.

The Golden Stool was a symbol of Asante unity.

In the face of this insult the chiefs held a secret meeting at Kumasi.

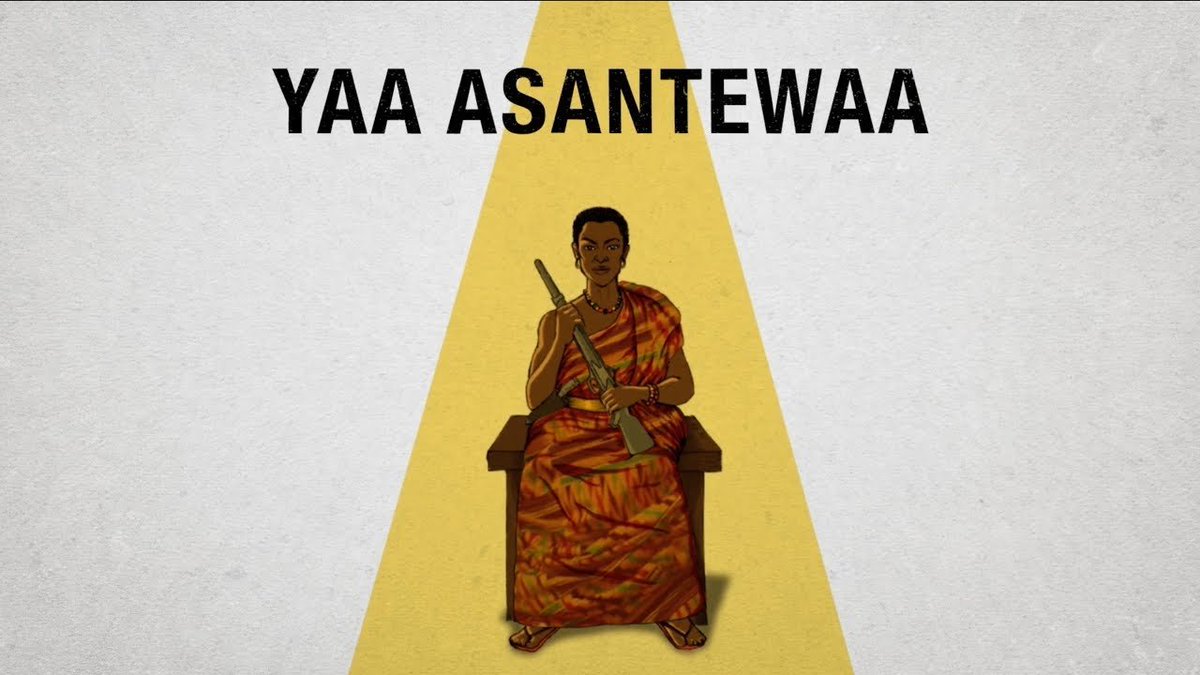

Yaa Asantewa, the Queen Mother of Ejisu, was at the meeting.

The chiefs were discussing how they could make war on the white men and force them to bring back the Asantehene.

Yaa Asantewa, the Queen Mother of Ejisu, was at the meeting.

The chiefs were discussing how they could make war on the white men and force them to bring back the Asantehene.

Yaa Asantewa saw that some of the bravest male members of nation were cowed.

In her now famous challenge, Yaa Asantewa declared:

How can a proud and brave people like the Asante sit back and look while white men took away their king and chiefs and humiliate them

In her now famous challenge, Yaa Asantewa declared:

How can a proud and brave people like the Asante sit back and look while white men took away their king and chiefs and humiliate them

with a demand for the Golden Stool.

The Golden Stool only means money to the white man; they searched and dug everywhere for it . . . If you, the chiefs of Asante, are going to behave like cowards and not fight, you should exchange your loincloths for my undergarments.

The Golden Stool only means money to the white man; they searched and dug everywhere for it . . . If you, the chiefs of Asante, are going to behave like cowards and not fight, you should exchange your loincloths for my undergarments.

That was the beginning of the Yaa Asantewa War.

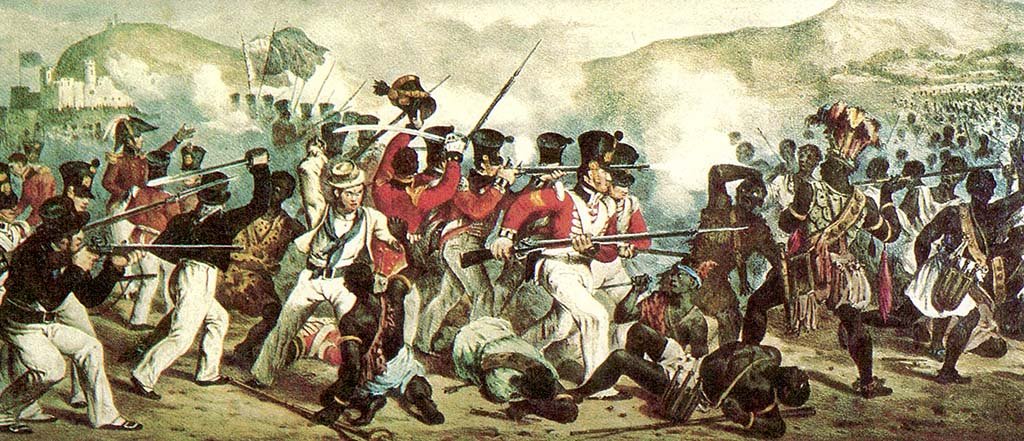

The final battle began on September 30, 1900, and ended in the bloody defeat of the Asante.

Yaa Asantewa was the last to be captured, and subsequently exiled to the Seychelles, where she died around 1921.

The final battle began on September 30, 1900, and ended in the bloody defeat of the Asante.

Yaa Asantewa was the last to be captured, and subsequently exiled to the Seychelles, where she died around 1921.

With the end of these wars, the British gained control of the hinterland of Ghana.

Around the same time, Behanzin, the last king of Dahomey (1889-94), told the European envoy that came to see him:

God has created Black and White, each to inherit its designated territory.

Around the same time, Behanzin, the last king of Dahomey (1889-94), told the European envoy that came to see him:

God has created Black and White, each to inherit its designated territory.

The White man is concerned with commerce and the Black man must trade with the White. Let the Blacks do no harm to the Whites and in the same way the Whites must do not harm to the blacks.

In 1895, Wobogo, the Moro Nabaor king of the Mossi told French Captain Restenave:

In 1895, Wobogo, the Moro Nabaor king of the Mossi told French Captain Restenave:

I know the whites wish to kill me in order to take my country, and yet you claim that they will help me to organize my country.

But I find my country good just as it is. I have no need of them.

I know what is necessary for me and what I want: I have my own merchants:

But I find my country good just as it is. I have no need of them.

I know what is necessary for me and what I want: I have my own merchants:

also, consider yourself fortunate that I do not order your head to be cut off.

Go away now, and above all, never come back.

Alliance

When West African leaders struck alliances with the imperialists, they did so in an attempt to enhance their commercial

Go away now, and above all, never come back.

Alliance

When West African leaders struck alliances with the imperialists, they did so in an attempt to enhance their commercial

and diplomatic advantages.

King Jaja of Opobo, for instance, resorted to diplomacy as means of resistance to European intrusive imperialism.

Mbanaso Ozurumba, a.k.a Jaja was a former slave of Igbo origin.

He was elected as king of the Anna Pepple House in Bonny, Niger Delta,

King Jaja of Opobo, for instance, resorted to diplomacy as means of resistance to European intrusive imperialism.

Mbanaso Ozurumba, a.k.a Jaja was a former slave of Igbo origin.

He was elected as king of the Anna Pepple House in Bonny, Niger Delta,

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh