8: Colonial Rule in West Africa

wasscehistorytextbook.com/8-colonial-rul…

History Textbook

West African Senior School Certificate Examination

(continued 6/6)

West African Response and Initiatives

The imposition of foreign domination on West Africa did

not go unchallenged.

wasscehistorytextbook.com/8-colonial-rul…

History Textbook

West African Senior School Certificate Examination

(continued 6/6)

West African Response and Initiatives

The imposition of foreign domination on West Africa did

not go unchallenged.

West Africans adopted different strategies to ensure survival.

Some West African people living outside the cash crop areas found that they could get away with very little contact with the Europeans.

Others exploited the system

Some West African people living outside the cash crop areas found that they could get away with very little contact with the Europeans.

Others exploited the system

for their own gain by playing on the colonial government’s ignorance of specific regions’ histories.

Still others pursued Western education and Christianity while holding strong to their identities.

West African people struggled against the breaking up of

Still others pursued Western education and Christianity while holding strong to their identities.

West African people struggled against the breaking up of

their historical states as well as any threat to their land through petitions, litigations, uprisings.

Early Protest Movements

West Africans organized protest against colonialism in form of the assertion of the right to self-rule.

Early Protest Movements

West Africans organized protest against colonialism in form of the assertion of the right to self-rule.

Some of the most notable movements included: (1) The Fante Confederacy (1868-72) of the Gold Coast, which recommended British withdrawal from all of her West African colonies; (2) The Egba United Board of Management (1865) of Nigeria, which aimed to introduce legal reforms

and tolls on European lines, establish postal communications in Lagos; (3) The aborigines Rights Protection Society (1897) of the Gold Coast was formed to oppose government proposals to classify unoccupied land as crown land (meaning that the land belongs to government).

In the 1920’s colonial administration succeeded in breaking alliance by supporting chiefs against the elite; (4) The National Congress of British West Africa (1920).

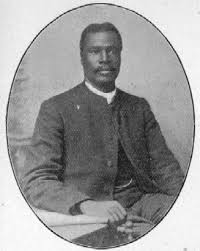

The Congress was formed in Accra in 1920 under the leadership of J. E. Casely-Hayford, an early nationalist,

The Congress was formed in Accra in 1920 under the leadership of J. E. Casely-Hayford, an early nationalist,

and distinguished Gold Coast lawyer. Its aims were to press for constitution and other reforms, demand Legislative Council in each territory with half of members made up of elected Africa.

They opposed discrimination against Africans in civil service,

They opposed discrimination against Africans in civil service,

asked for a West African university, and asked for stricter immigration controls to exclude “undesirable” Syrians (business elite).

The African Church Movement or Ethiopianism

In the religious sphere, the Creoles played an important role in Christianizing many parts

The African Church Movement or Ethiopianism

In the religious sphere, the Creoles played an important role in Christianizing many parts

of West Africa including, Sierra Leone, Lagos, Abeokuta, and the Niger Delta.

However, they soon met with the same kind of British racial arrogance encountered by West Africans in the colonial government.

However, they soon met with the same kind of British racial arrogance encountered by West Africans in the colonial government.

The British replaced Creole archbishops and superintendents with Europeans. A European succeeded Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther, and no African was consecrated to this high office again for next sixty years.

The West African response to this was to break away from

The West African response to this was to break away from

European churches and form new, independent West African churches.

These churches included: the African Baptists, United Native African Church, African Church, United African Methodists—all in Nigeria, the United Native Church in Cameroon;

These churches included: the African Baptists, United Native African Church, African Church, United African Methodists—all in Nigeria, the United Native Church in Cameroon;

and the William Harry Church in Ivory Coast. By 1920, there were no less than 14 churches under exclusive African control. In Fernando Po, Reverend James Johnson was leading figure of the African church movement until his death in 1917.

The Independence movement among churches demanded that control be vested in West African lay or clerical leaders. Many churches incorporated aspects of West African ideas of worship into their liturgies, showing more tolerance for West African social institutions like polygamy.

The Prophetic Church Movement also emerged during this time, propelling the establishment of at least three prominent churches in West Africa which related Christianity to current West African beliefs.

These prophets offered prayers for the problems that plagued people

These prophets offered prayers for the problems that plagued people

in villages, problems which traditional diviners had previously offered assistance in form of sacrifices to various gods.

The Prophet Garrick Braide movement Began in 1912, ending with imprisonment in 1916. The Prophet William Wade Harris movement began in 1912,

The Prophet Garrick Braide movement Began in 1912, ending with imprisonment in 1916. The Prophet William Wade Harris movement began in 1912,

reached its height in 1914-15, spreading his gospel in the Ivory Coast, Liberia, and Gold Coast.

The Aladura (people of prayer) Movement in Western Nigeria, began during the influenza epidemic (1918-19), achieving its greatest impact during Great Revival of 1930.

The Aladura (people of prayer) Movement in Western Nigeria, began during the influenza epidemic (1918-19), achieving its greatest impact during Great Revival of 1930.

The African Church and prophetic movement was represented a nationalist reaction against white domination in religious sphere, whim encouraged Africans to adopt African names at baptism, adapt songs to traditional flavors, and translate the bible

and prayer books into West African languages.

Despite the rapid spread of Christianity in West Africa, Islam was spreading even more rapidly. West Africans embraced Islam as a form of protest against colonialism

Despite the rapid spread of Christianity in West Africa, Islam was spreading even more rapidly. West Africans embraced Islam as a form of protest against colonialism

because it offered a wider world view devoid of the indignity of assimilation to the colonial master’s culture.

The Ethiopian Crisis, 1935

West Africans were jolted towards radicalism by Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935.

The Ethiopian Crisis, 1935

West Africans were jolted towards radicalism by Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935.

Ethiopia held a special significance for colonized Africans. It was an ancient Christian kingdom, an island of freedom in a colonized continent.

Ethiopia was taken as symbol for African and African Christians. Nkrumah who was in London at time later recalled,

Ethiopia was taken as symbol for African and African Christians. Nkrumah who was in London at time later recalled,

“at that time it was almost as if the whole of London had suddenly declared war on me personally.”

While the various missionary societies proselytizing in West Africa, introduced schools of European learning in their

While the various missionary societies proselytizing in West Africa, introduced schools of European learning in their

West African dominions, as noted above, these for the most part, were far and few between.

After the introduction of indirect rule, for instance, the British discouraged West Africans from acquiring higher education by denying them employment in the colonial administrations.

After the introduction of indirect rule, for instance, the British discouraged West Africans from acquiring higher education by denying them employment in the colonial administrations.

They instead subsidized Christian missions to produce more clerks and interpreters.

The French government on their part, limited the number of schools in their West African territories. Indeed, Senegal was the only colony that had secondary schools; and of these schools,

The French government on their part, limited the number of schools in their West African territories. Indeed, Senegal was the only colony that had secondary schools; and of these schools,

the William Ponty school in Dakar was the oldest and most popular.

Nwando Achebe

(follow link for total article, longer than I set out to do. Evie)

wasscehistorytextbook.com/8-colonial-rul…

Nwando Achebe

(follow link for total article, longer than I set out to do. Evie)

wasscehistorytextbook.com/8-colonial-rul…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh