8: Colonial Rule in West Africa

wasscehistorytextbook.com/8-colonial-rul…

History Textbook

West African Senior School Certificate Examination

(continued 4/6)

Thus, in the 1920s, the policy was changed to the policy of association, which was advocated as the most appropriate for French Africa.

wasscehistorytextbook.com/8-colonial-rul…

History Textbook

West African Senior School Certificate Examination

(continued 4/6)

Thus, in the 1920s, the policy was changed to the policy of association, which was advocated as the most appropriate for French Africa.

On paper, association reorganized the society supposedly to achieve maximum benefit for both the French and the West African.

In practice however, scholars have argued that this policy was like the association of a horse and its rider,

In practice however, scholars have argued that this policy was like the association of a horse and its rider,

since the French would at all times dictate the direction that the development should take and determine what would be of mutual benefit to themselves and West Africans.

The colonial belief in the superiority of French civilization was reflected in the judicial system,

The colonial belief in the superiority of French civilization was reflected in the judicial system,

their attitude toward indigenous law, indigenous authorities, indigenous rights to land, and the educational program. They condemned everything African as primitive and barbaric.

Actual Administration

The French employed a highly centralized and

Actual Administration

The French employed a highly centralized and

authoritarian system of administration. Between 1896 and 1904, they formed all of their eight West African colonies into the Federation of French West Africa (AVF), with its capital at Dakar.

At the head of Federation was governor-general who answered

At the head of Federation was governor-general who answered

to minister of colonies in Paris, took most of his orders from France, and governed according to French laws.

At the head of each colony was the Lt.-governor who was assisted by a council of administration.

The Lt.-governor was directly under the governor-general

At the head of each colony was the Lt.-governor who was assisted by a council of administration.

The Lt.-governor was directly under the governor-general

and could make decisions on only a few specified subjects.

The French policy of assimilation, was a policy of direct rule through appointed officials.

Like British, they divided their colonies into regions and districts.

The French policy of assimilation, was a policy of direct rule through appointed officials.

Like British, they divided their colonies into regions and districts.

The colonies were divided into cercles under the commandants du cercles. Cercles were divided into subdivisions under Chiefs du Subdivision.

Subdivisions were divided into cantons under African chiefs.

Subdivisions were divided into cantons under African chiefs.

Distinguishing Features

African Chiefs were not local government authorities.

They could not exercise any judicial functions.

They did not have a police force or maintain prisons.

African chiefs were not leaders of their people. Rather, they were mere functionaries,

African Chiefs were not local government authorities.

They could not exercise any judicial functions.

They did not have a police force or maintain prisons.

African chiefs were not leaders of their people. Rather, they were mere functionaries,

supervised by French political officers.

African chiefs were appointed, not by birth, but rather by education, and familiarity with the metropolitan administrative practice.

African chiefs could be transferred from one province to another.

African chiefs were appointed, not by birth, but rather by education, and familiarity with the metropolitan administrative practice.

African chiefs could be transferred from one province to another.

The French policy actually went out of its way to deliberately destroy traditional paramountcies.

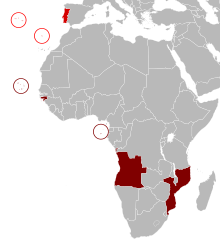

The Portuguese in West Africa

Administrative Policies

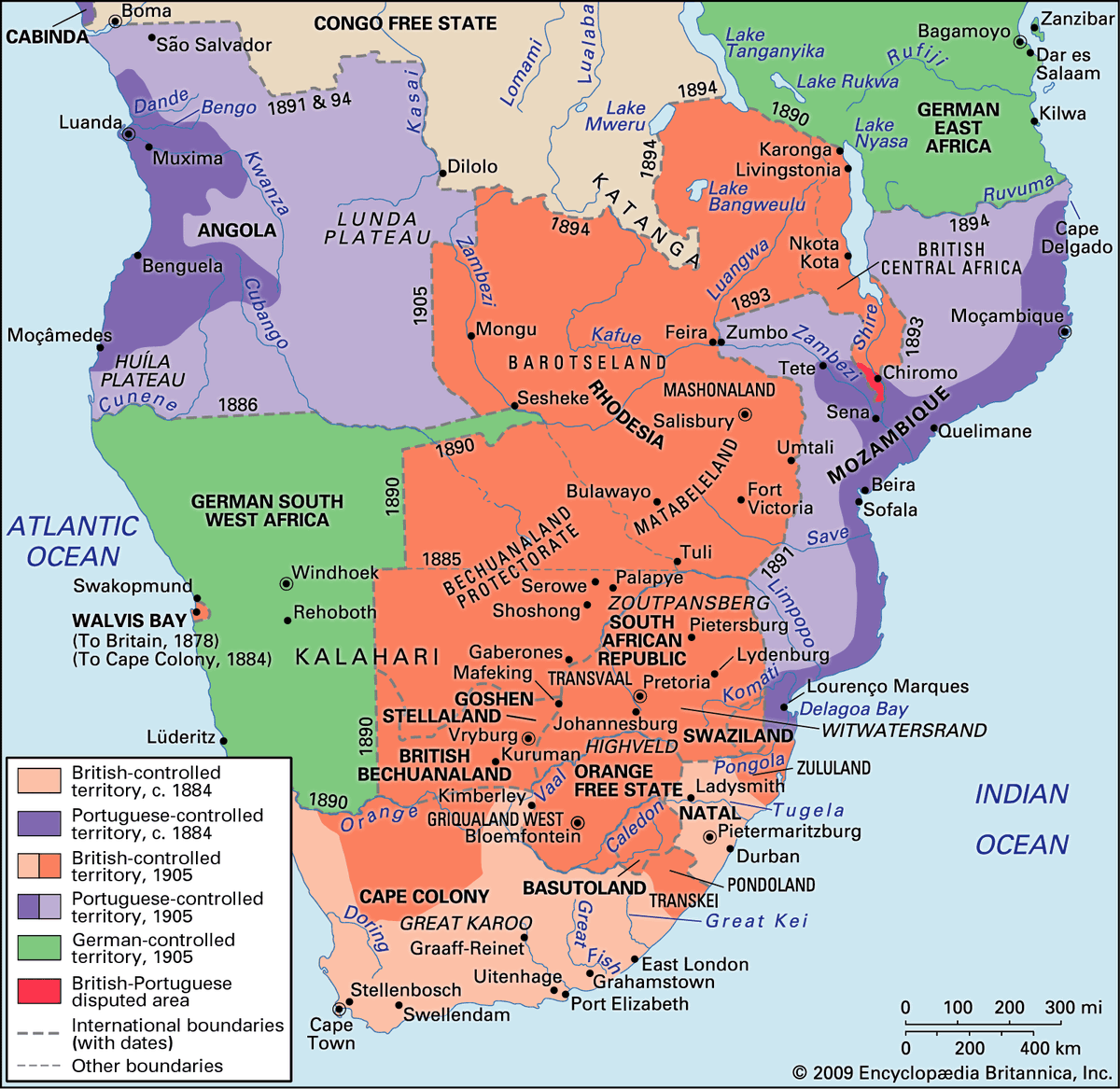

Portugal, one of the poorest of the European colonist nations in Africa operated what amounted to a closed economic system

The Portuguese in West Africa

Administrative Policies

Portugal, one of the poorest of the European colonist nations in Africa operated what amounted to a closed economic system

in their African colonies.

They created a system which welded their West African colonies to mother country, Portugal, both politically and economically.

As such, their territories in West Africa were considered overseas provinces and integral part of Portugal.

They created a system which welded their West African colonies to mother country, Portugal, both politically and economically.

As such, their territories in West Africa were considered overseas provinces and integral part of Portugal.

Actual Administration

One underlying connection of all West African Portuguese colonies was the presence of relatively large numbers of Portuguese in the colonies, especially after 1945 when there was a full-scale emigration program from Portugal, especially to Angola.

One underlying connection of all West African Portuguese colonies was the presence of relatively large numbers of Portuguese in the colonies, especially after 1945 when there was a full-scale emigration program from Portugal, especially to Angola.

The Portuguese operated a very authoritarian and centralized system of government. At the top of government was the Prime Minister. Under him were the Council of Ministers and the Overseas Ministry, which was made up of the Overseas Advisory Council,

and the General Overseas Agency.

Then there was the Governor General, a Secretariat and Legislative Council. All of these offices were in Portugal.

There were also Governors of Districts, Administrators of Circumscricoes,

Then there was the Governor General, a Secretariat and Legislative Council. All of these offices were in Portugal.

There were also Governors of Districts, Administrators of Circumscricoes,

Chefes de posto and at the very bottom of the governmental hierarchy, the African Chiefs.

As in the British case, the Portuguese corrupted the systems of chieftaincies. They sacked chiefs who resisted colonial rule in Guine, and replaced them with more pliant chiefs.

As in the British case, the Portuguese corrupted the systems of chieftaincies. They sacked chiefs who resisted colonial rule in Guine, and replaced them with more pliant chiefs.

Thus, the historical authority of chiefs and their relationships with subjects was corrupted to one of authoritarianism which reproduced the authoritarian system of government in the Estado Novo dictatorship (1926-74).

Real authority was held by the Portuguese council of ministers, which was controlled by the prime minister. The direction of colonial policy was determined by the overseas ministry, aided by the advisory overseas council and two subsidiary agencies.

The governor-general appointed the chief official resident for the colony. The chief official of the resident for the colony had far reaching executive and legislative power. He headed the colonial bureaucracy, directed the native authority system,

and was responsible for the colonies’ finances.

The Circumscricoes and Chefes de posto roughly corresponded to the British provincial and district officers. They collected taxes, were judges and finance officers. West African chiefs were subordinate to the European officers

The Circumscricoes and Chefes de posto roughly corresponded to the British provincial and district officers. They collected taxes, were judges and finance officers. West African chiefs were subordinate to the European officers

with little power to act on their own. Moreover, they could be replaced at any time by a higher Portuguese power.

The political policy adopted in Guinea Bissau, São Tomé, Principe, and Cape Verdes, Portugal’s West African territories was a system of assimilado.

The political policy adopted in Guinea Bissau, São Tomé, Principe, and Cape Verdes, Portugal’s West African territories was a system of assimilado.

The assimilado policy held that all persons, no matter their race, would be accorded this status if they met the specific qualifications. Similar to the French policy of assimilation, the Portuguese West African had to adopt a European mode of life; speak

and read Portuguese fluently; be a Christian; compete military service; and have a trade or profession. However, only a small number Portuguese West Africans became assimilados because of the difficulty in achieving this station.

As in the British case, the Portuguese corrupted the systems of chieftaincies.

They sacked chiefs who resisted colonial rule in Guine, and replaced them with more pliant chiefs. Thus, the historical authority of chiefs and their relationships with

They sacked chiefs who resisted colonial rule in Guine, and replaced them with more pliant chiefs. Thus, the historical authority of chiefs and their relationships with

subjects was corrupted to one of authoritarianism which reproduced the authoritarian system of government in the Estado Novo dictatorship (1926-74).

Real authority was held by the Portuguese council of ministers, which was controlled by the prime minister.

Real authority was held by the Portuguese council of ministers, which was controlled by the prime minister.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh