8: Colonial Rule in West Africa

wasscehistorytextbook.com/8-colonial-rul…

History Textbook

West African Senior School Certificate Examination

(continued 5/6)

The direction of colonial policy was determined by the overseas ministry, aided by the advisory overseas council

wasscehistorytextbook.com/8-colonial-rul…

History Textbook

West African Senior School Certificate Examination

(continued 5/6)

The direction of colonial policy was determined by the overseas ministry, aided by the advisory overseas council

and two subsidiary agencies.

The governor-general appointed the chief official resident for the colony. The chief official of the resident for the colony had far reaching executive and legislative power. He headed the colonial bureaucracy, directed the native authority system,

The governor-general appointed the chief official resident for the colony. The chief official of the resident for the colony had far reaching executive and legislative power. He headed the colonial bureaucracy, directed the native authority system,

and was responsible for the colonies’ finances.

The Circumscricoes and Chefes de posto roughly corresponded to the British provincial and district officers. They collected taxes, were judges and finance officers.

The Circumscricoes and Chefes de posto roughly corresponded to the British provincial and district officers. They collected taxes, were judges and finance officers.

West African chiefs were subordinate to the European officers with little power to act on their own. Moreover, they could be replaced at any time by a higher Portuguese power.

The political policy adopted in Guinea Bissau, São Tomé, Principe,

The political policy adopted in Guinea Bissau, São Tomé, Principe,

and Cape Verdes, Portugal’s West African territories was a system of assimilado.

The assimilado policy held that all persons, no matter their race, would be accorded this status if they met the specific qualifications.

The assimilado policy held that all persons, no matter their race, would be accorded this status if they met the specific qualifications.

Similar to the French policy of assimilation, the Portuguese West African had to adopt a European mode of life; speak and read Portuguese fluently; be a Christian; compete military service; and have a trade or profession.

However, only a small number Portuguese West Africans became assimilados because of the difficulty in achieving this station.

Additionally, the Portuguese did not support education in their colonies.

Additionally, the Portuguese did not support education in their colonies.

They built few secondary schools, and almost entirely neglected elementary education.

Most of their emphasis was given to rudimentary levels of training where Portuguese West African students were taught moral principles and basic Portuguese; making it almost impossible

Most of their emphasis was given to rudimentary levels of training where Portuguese West African students were taught moral principles and basic Portuguese; making it almost impossible

for the Portuguese West African, even if she or he wanted to, to achieve the status of assimilado.

The Germans in West Africa

Administrative Policies

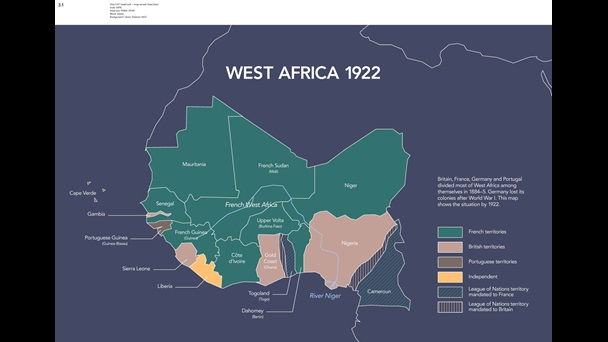

The Germans had two territories in West Africa—Togo and Kameroon.

The Germans in West Africa

Administrative Policies

The Germans had two territories in West Africa—Togo and Kameroon.

German colonialism was too short-lived to establish a coherent administrative policy. German African colonial experience essentially amounted to thirty years (1884-1914) and was characterized by bloody African rebellions.

However, their harsh treatment resulted in intervention and direct rule by German government.

The German colonialists envisioned a “New Germany” in Africa in which colonialists would be projected as members of a superior and enlightened race;

The German colonialists envisioned a “New Germany” in Africa in which colonialists would be projected as members of a superior and enlightened race;

while Africans were projected as inferior, indolent, and destined to be permanent subjects of Germans.

Actual Administration

The Germans had a highly centralized administration. At the top of government was the Emperor. The Emperor was assisted by the Chancellor,

Actual Administration

The Germans had a highly centralized administration. At the top of government was the Emperor. The Emperor was assisted by the Chancellor,

who was assisted by Colonial Officers, who supervised the administration.

At the bottom were the jumbes or subordinate African staff. These men had been placed in the stead of recognized leadership.

At the bottom were the jumbes or subordinate African staff. These men had been placed in the stead of recognized leadership.

European Economic and Social Policies in their West African Dominions

The cardinal principles of the European colonial economic relationship in West Africa were to: (1) stimulate the production and export of West African cash crops including palm produce, groundnuts,

The cardinal principles of the European colonial economic relationship in West Africa were to: (1) stimulate the production and export of West African cash crops including palm produce, groundnuts,

cotton, rubber, cocoa, coffee and timber; (2) encourage the consumption and expand the importation of European manufactured goods; (3) ensure that the West African colony’s trade, both imports and exports, were conducted with the metropolitan European country concerned.

The colonialists thus instituted the Colonial Pact which ensured that West African colonies must provide agricultural export products for their imperial country and buy its manufactured goods in return, even when they could get better deals elsewhere.

To facilitate this process, the colonialists therefore forced West Africans to participate in a monetized market economy.

They introduced new currencies, which were tied to currencies of the metropolitan countries to replace the local currencies and barter trade.

They introduced new currencies, which were tied to currencies of the metropolitan countries to replace the local currencies and barter trade.

Railroads were a central element in the imposition of the colonial economic and political structures. Colonial railways did not link West African economies and production together.

They did not link West African communities together either,

They did not link West African communities together either,

rather they served the purpose of linking West African producers to international trade and market place; and also connecting production areas to the West African coast.

Moreover, railroads meant that larger amounts of West African produced crops could be sent to coast.

Moreover, railroads meant that larger amounts of West African produced crops could be sent to coast.

All equipment used to build and operate the railroads were manufactured in Europe, and brought little to no economic growth to West Africa beyond reinforcing the production of West African cash crops for the external market.

What was more, thousands of West African men were forced to construct these railroads; and many died doing so.

The key to the development of colonial economies in West Africa, was the need to control labor. In the colonies, this labor was forced.

The key to the development of colonial economies in West Africa, was the need to control labor. In the colonies, this labor was forced.

There were basically two types of forced labor in Africa. The first, was peasant labor. This occurred in most parts of West Africa where agriculture was already mainstay. In East, Central, and South Africa, Africans performed migrant wage labor on European owned

and managed mines and plantations.

The colonial masters also imposed taxation in West Africa. By taxing rural produce, the colonial state could force West Africans to farm cash crops.

West Africans had to sell sustenance crops on the market for cash.

The colonial masters also imposed taxation in West Africa. By taxing rural produce, the colonial state could force West Africans to farm cash crops.

West Africans had to sell sustenance crops on the market for cash.

Then use cash to pay taxes. Taxes could be imposed on land, produce, and homes (hut tax). The requirement to pay tax forced West Africans into the colonial labour market.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh