I've noticed people sometimes use 'herd immunity' to mean 'pathogen fades to zero and stays there' rather than the technical definition (i.e. R drops below 1 because of accumulated immunity, without NPIs). Why is the distinction important? 1/

https://twitter.com/AdamJKucharski/status/1316283049445855232?s=20

If we're talking about 'fades to zero', we're really talking about elimination or eradication as a result of accumulated immunity. So has this ever occurred in the absence of a vaccine? 2/

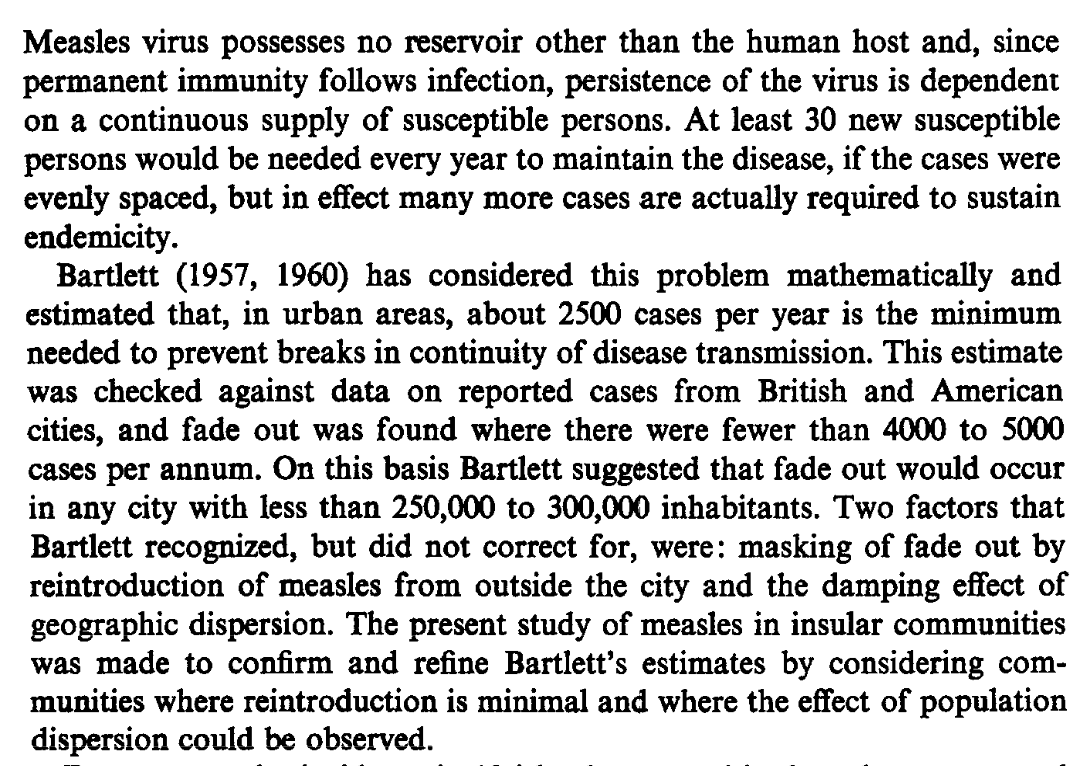

There are no examples of eradication (i.e. no infections globally) as a result of accumulated natural immunity, rather than from a vaccine-induced immunity or NPIs (like smallpox). 3/

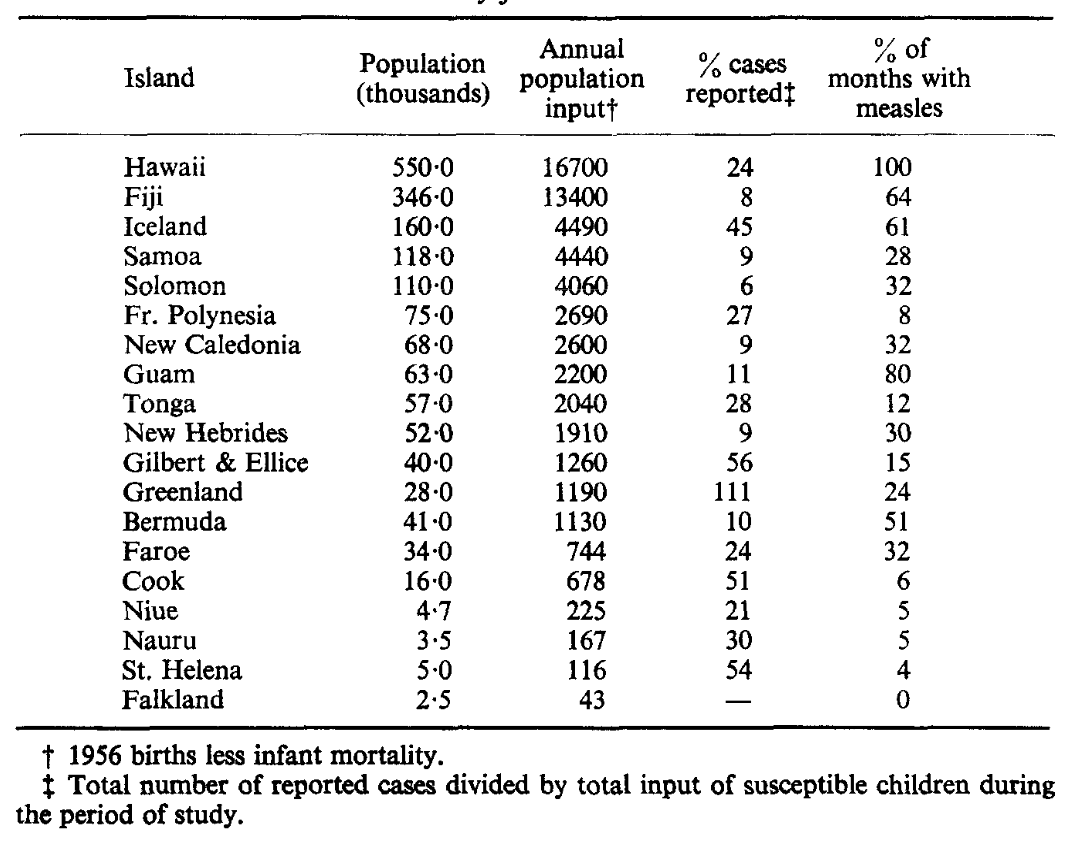

There are examples of local elimination of transmission as result of natural immunity, like measles in small isolated populations – there is typically a 'critical community size', below which outbreaks can't be sustained without imports. (Below from: sciencedirect.com/science/articl…) 4/

Why do these subtleties matter? As COVID vaccine coverage increases, there will be growing discussion of 'herd immunity', 'elimination' and 'endemic infection' - these discussions will be far more constructive if we define these concepts precisely. 5/5

Footnote: Unfortunately, of course, this isn't a new problem (below from: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11763/)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh