I've been having a lot of conversations about deficits, fiscal and monetary policy right now & frustrated with how many basic facts about our economy are misrepresented. So for Valentines Day, a #nerdthread on our national finances. Hope you enjoy:

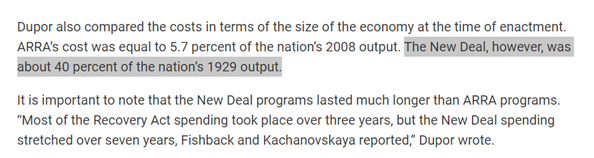

1/ First, prior to COVID, the biggest ever emergency funding program in our history was the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, passed in response to the 2008 crisis. Just shy of $700B in emergency funding.

2/ (In 2008 $. I leave to other nerdier nerds to adjust these numbers for inflation.)

3/ The CARES Act, passed in response to COVID was more than twice that big at $1.8T. The 2020 year end omnibus spending bill included an additional $900B.

4/ In other words, the top two largest emergency funding bills in our nation's history were passed in the last year. Both are bigger than ARRA. And we are finalizing terms of an additional $1.9T.

5/ This has raised all sorts of completely reasonable questions about how we are going to pay for this, impacts on long term deficits, etc. As it should. But if all we talk about is fiscal policy, we are telling a massively incomplete story.

6/ In 2008, with the economy in freefall, Congress approved the aforementioned ~$700B ARRA. It wasn't anywhere near enough to meet the need, but it was the most that political will would tolerate. And so monetary policy came to the rescue.

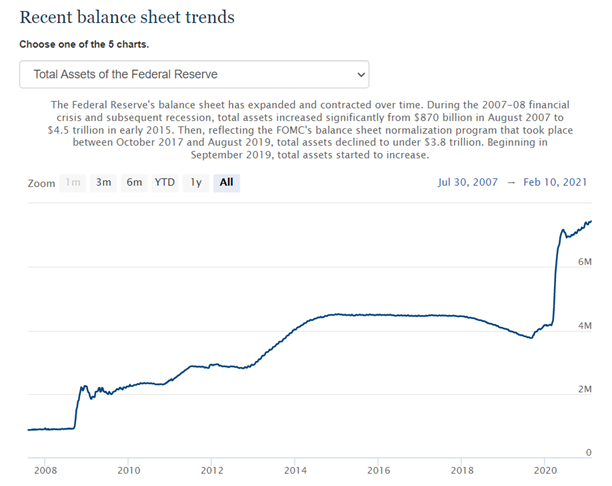

7/ The Federal Reserve massively expanded its balance sheet, injecting nearly 4x as much money into the economy over the next decade as the ARRA provided. federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy…

8/ The bulk of this came through the purchase of US treasuries, aka Quantitative Easing, or "QE" fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TREAST

9/ In other words, the $800B in fiscal policy expansion really wasn't the story of the 2008 recovery. The $4T in monetary policy expansion was. And while fiscal policy was constrained by politics, monetary policy wasn't. (Thankfully: Politically independent Fed = good.)

10/ But the fact that it is politically easier to flex (up or down) with monetary rather than fiscal policy also means that our political system is biased to over-use monetary at the expense of fiscal policy. And their impacts are quite different.

11/ Monetary policy is very good at injecting money into the banking system. It's not especially good at getting money to the under-banked, or to long-dated infrastructure, or to R&D activities with uncertain return, or to hard-to-monetize social welfare.

12/ Fiscal policy is good at doing all those things that monetary policy is bad at, but is bad at optimizing capital flows to the private sector. Which is to say that good overall policy strikes a prudent balance between the two.

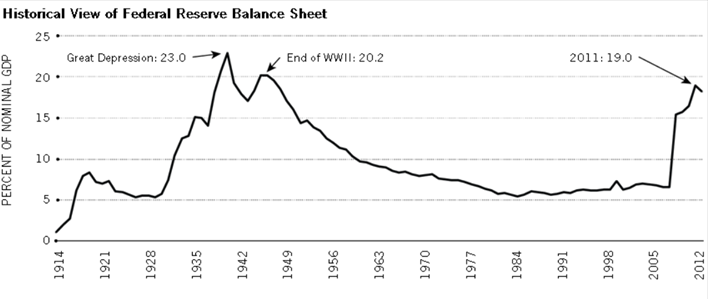

13/ So now some history. In the Depression / New Deal era the fed balance sheet (aka monetary policy) got as high as 23% of GDP. stlouisfed.org/~/media/Public…

14/ But meanwhile, the New Deal - e.g., fiscal policy - was 40% of 1929 GDP. stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy…

15/ To be clear there is no perfect balance of fiscal and monetary policy. But you can't have an honest conversation about debt and deficits without including both. And - since 2008 - we have relied extensively on monetary, rather than fiscal tools.

16/ That has, in no small part increased wealth inequality even as it has helped sustain the Obama economic boom. (Remember, monetary policy isn't well structured to address social welfare, but it is good at boosting GDP.)

17/ So as big as our recent fiscal measures have been, they should also be seen as an overdue corrective re-balancing of our fiscal / monetary policy ratio.

18/ And when we emerge from the COVID downturn, the independence of the Fed will be an asset - in the same way that it was politically easier to "flex up" monetary policy after 2008, it will be politically easy to "flex down" on that side if the economy starts to overheat.

19/ We will be watching all these issues closely on the Financial Services Committee where I am proud to serve. In the meantime, I hope you all enjoy snuggling up by the fire with someone you love and reading them this thread for Valentines Day. Much love. /fin

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh