Following the recent @realbrainbook CBD, this #tweetorial is going to address the basis for the neurological findings you expect to see in acute cauda equina syndrome, how to approach this often-misunderstood condition systematically, and some tips and tricks. #CES #FOAMed 1/24

The cauda equina (CE) is the bundle of lumbosacral spinal nerves destined for the legs, perineum, bladder and bowel. Any pathology in this area can cause 'cauda equina' features, but I'm going to focus on the emergency condition, usually caused by an acute disc prolapse. 2/24

Here is a view from behind of the lumbar vertebrae 1-5, the top of the sacrum and the intervening discs. The backs of all the lumbar vertebrae except L5 have been removed so you can see inside. Here is the CE, starting below L1/2 where the spinal cord terminates (the conus). 3/24

Let's look at an axial slice through one level (L3/4 for diagrammatic reasons - although disc prolapse is much more common at L4/5 and L5/S1). On the MRI you can see the triangular spinal canal, enclosing the CE nerve roots (black dots) suspended freely in CSF (white). 4/24

Discs usually prolapse posteriorly to one side, simply because the enclosing PLL ligament is deficient here. You can see how this can compress a nerve, causing sciatica. It usually affects the 'transiting' one (L4 at this level) but if really lateral, the 'exiting' L3 root. 5/24

Here's what happens in CES. The disc prolapses posteriorly and centrally. See on the MRI how that triangular spinal canal is obliterated, with none of the white CSF visible. This means the CE nerves are under compression. Coupled with the right history, it's an emergency. 6/24

So what is the 'right history' for acute CES? I always found it terribly confusing - leg pain, weakness, perineal numbness, urinary incontinence, retention, faecal incontinence... how do you disentangle all this? I do so by applying its 'natural history' to give 4 stages. 7/24

Without intervention, acute CE compression generates the following increasingly serious clinical stages - though note that people progress at completely different rates, and may skip stages. For this reason, the length of the history and rate of progression are key. 8/24

CES Suspected (CESS): this patient has bilateral sciatica +/- bilateral lower limb neurology, but no perineal/bladder/bowel symptoms. It's not CES yet - but bilateral symptoms imply a central lesion (compressing nerves on both sides of the canal), so CES could be impending. 9/24

CES Incomplete (CESI): perineal/bladder/bowel features with normal post-void bladder scan (<100-150mL depending who you ask). This patient has sphincter disturbance but objectively normal bladder function - and has a good outcome with emergency surgery. 10/24

CES with Retention (CESR) - as above but in urinary retention. Outcomes at this stage are already worse than CESI. In early CESR, retention will be painful (as one would expect) - but as it progresses it becomes insensate with loss of all bladder sensation. 11/24

CES Complete (CESC) - >48h insensate urinary retention. This patient will have lost all executive control of bladder and bowel. Overflow urinary incontinence, absent anal tone, manual evacuations, no sexual function - this outcome needs to be prevented at all costs. 12/24

So how should you assess the patient to determine which category to put them in? When should you get an MRI? With back pain being such a common problem, here are a few history, examination and investigation/management 'tips and tricks'... 13/24

Hx #1 - any bladder, bowel or perineal sensory disturbance should be taken seriously. In general, sensory symptoms precede motor ones - L5 numbness before a foot drop, an incontinence episode due to altered bladder sensation before retention due to detrusor paralysis. 14/24

Hx #2 - in true cases of acute CES there tends to be a clear story of progression over hours to days. So for example, chronic urinary incontinence, a spell of particularly bad unilateral sciatica but no new examination findings doesn't really fit. 15/24

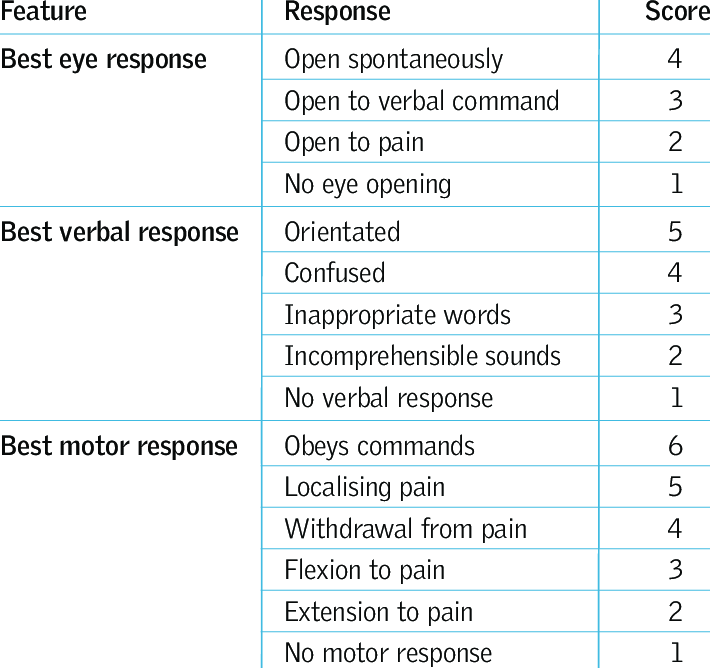

O/E #1 - Examine tone, reflexes, and upper limbs. The CE is below the termination of the cord and not part of the CNS, so expect lower motorneuron signs in the lower limbs. Brisk reflexes/upper limb signs/sensory level in the torso → needs whole spine MRI. 16/24

O/E #2 - Learn the ASIA spinal injury chart key sensory points (see link). Much easier to nail than dermatome maps. Then you can confidently work out the dermatomal distribution of symptoms and any objective numbness.

asia-spinalinjury.org/wp-content/upl… 17/24

asia-spinalinjury.org/wp-content/upl… 17/24

O/E #3 - Perianal pinprick sensation is more sensitive (literally!) than fine touch. A prod with a Neurotip should be felt, and should induce a reflex sphincter contraction if the sacral nerves are working. Check both sides; bilateral numbness to pinprick is very worrying. 18/24

O/E #4 - Anal tone is commonly confused with voluntary anal contraction and described as 'reduced'. Think of the difference between tone and power in the limbs. If tone is absent, the sphincter will be flaccid - very obvious, and a very late sign implying CESC. 19/24

Ix/Rx #1 - If post-void bladder scan volume is high, try a strong parenteral NSAID if not contraindicated, diazepam, and re-check. Once catheterised it's harder to assess bladder function. Ask if they felt it go in, or if a catheter tug is felt (the balloon on the bladder). 20/24

Ix/Rx #2 - It's really important to appreciate that no one symptom or sign predicts whether there's be CE compression on the scan. For this reason, in the context of back pain/sciatica, any feature of bladder, bowel or perineal sensory disturbance warrants urgent MRI. 21/24

Rx #2 - SBNS/BASS UK guidelines are that plain MRI lumbar spine should be available 24/7 locally, which it is not. So if considering acute CES within hours, don't delay the scan until evening - it should even disrupt an elective MRI list if necessary. 22/24

Rx #3 - If out of hours and the rate of progression implies the patient will be worse by your next MRI slot, discuss with neurosurgery about transfer for a scan. If advised to await a local slot, keep as inpatient and examine daily - progression should prompt re-discussion! 23/24

I hope this was helpful to those that assess patients 'at the front door' and in the community. It's by no means complete, so I'll try to answer questions about anything I've missed.

And for more - see @DrLindaDykes and @saspist's excellent work!

24/24

And for more - see @DrLindaDykes and @saspist's excellent work!

https://twitter.com/DrLindaDykes/status/1088787589665038338

24/24

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh