Thread on some of my favorite pieces from today's new post:

Technology & The Financial Printing Press

This thread will cover three main sections:

• The Printing Press

• Ticker Machines

• A 1930 Quant Fund

(1/25)

canvas.osam.com/Commentary/Blo…

Technology & The Financial Printing Press

This thread will cover three main sections:

• The Printing Press

• Ticker Machines

• A 1930 Quant Fund

(1/25)

canvas.osam.com/Commentary/Blo…

(2/25)

The honorable @wolfejosh said on his podcast with @patrick_oshag :

"If you want change and progress, somebody's got to look at something and literally go back to those two words and say, what sucks? That sucks.

And then you have to be motivated to want change it."

The honorable @wolfejosh said on his podcast with @patrick_oshag :

"If you want change and progress, somebody's got to look at something and literally go back to those two words and say, what sucks? That sucks.

And then you have to be motivated to want change it."

(3/25)

What I find interesting is that while technology usually solves this "what sucks" problem...

It can often produce new headaches itself, requiring further improvements and augmentations...

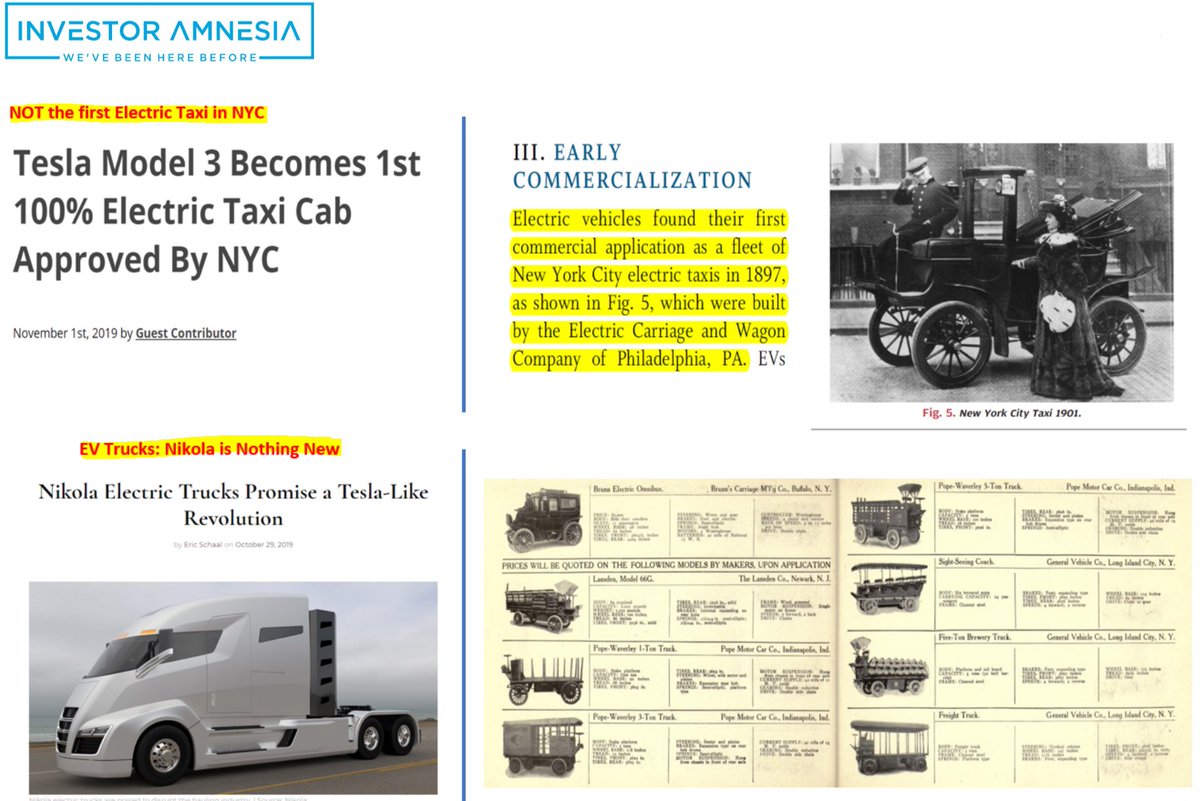

One great example: The Printing Press

What I find interesting is that while technology usually solves this "what sucks" problem...

It can often produce new headaches itself, requiring further improvements and augmentations...

One great example: The Printing Press

(4/25)

It is impossible to overstate the impact of the Printing Press on society.

• Broader readership

• Empowered community led movements (Martin Luther's 95 theses & the Protestant Reformation)

• Ensured greater accuracy in industries like science where this was crucial

It is impossible to overstate the impact of the Printing Press on society.

• Broader readership

• Empowered community led movements (Martin Luther's 95 theses & the Protestant Reformation)

• Ensured greater accuracy in industries like science where this was crucial

(5/25)

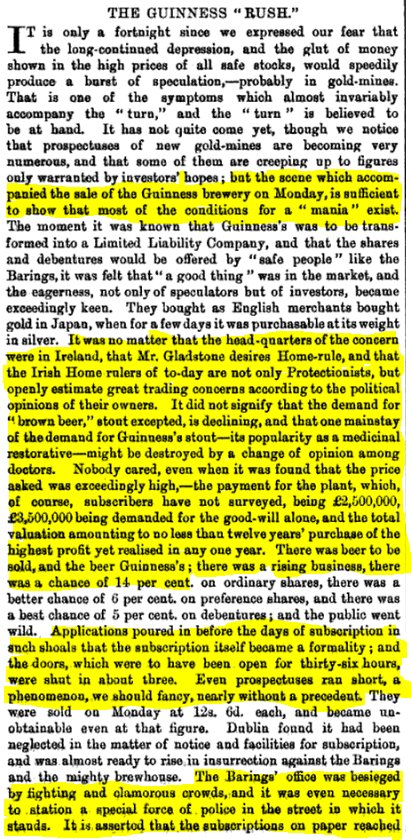

Obviously, however, the most notable impact was on the number of works published each year:

In *just* 1550 there were 3 million books produced across Western Europe; more than all the manuscripts published during the entire 14th century.

Obviously, however, the most notable impact was on the number of works published each year:

In *just* 1550 there were 3 million books produced across Western Europe; more than all the manuscripts published during the entire 14th century.

(6/25)

Yet, this technology led to a new problem similar to the one we have today:

Informational Abundance.

The explosion in printed works led to an onslaught of information that quickly became overwhelming.

Yet, this technology led to a new problem similar to the one we have today:

Informational Abundance.

The explosion in printed works led to an onslaught of information that quickly became overwhelming.

(7/25)

• "Is there anywhere on Earth exempt from these swarms of new books?" - Erasmus (1525)

• "That horrible mass of books [..] keeps on growing.” - Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1680)

• In 1581 a philosopher complained that no one could read every printed book in 10M years.

• "Is there anywhere on Earth exempt from these swarms of new books?" - Erasmus (1525)

• "That horrible mass of books [..] keeps on growing.” - Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1680)

• In 1581 a philosopher complained that no one could read every printed book in 10M years.

(8/25)

While the new technology was innovative and revolutionary, there were problems with the onslaught of information it produced.

The solution? Some familiar inventions to synthesize and distill info:

• First Book Reviews published

• Index Sections

• Table of Contents

While the new technology was innovative and revolutionary, there were problems with the onslaught of information it produced.

The solution? Some familiar inventions to synthesize and distill info:

• First Book Reviews published

• Index Sections

• Table of Contents

(9/25)

Of course, this led to complaints by authors that felt there works were suddenly not being appreciated.

Some authors went so far as to not even include an Index as a means of forcing people to read their entire book.

Of course, this led to complaints by authors that felt there works were suddenly not being appreciated.

Some authors went so far as to not even include an Index as a means of forcing people to read their entire book.

(10/25)

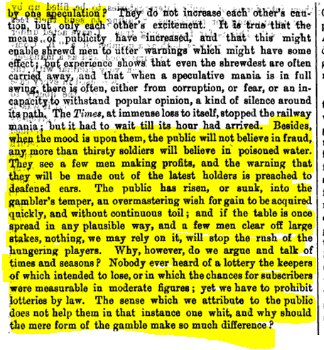

This all brings us back to the world of financial markets with the introduction of ticker machines in 1867.

Ticker Machines = Financial Printing Presses

This all brings us back to the world of financial markets with the introduction of ticker machines in 1867.

Ticker Machines = Financial Printing Presses

(11/25)

In 1903, Sereno Pratt stated the cornerstone of modern finance is “speed with accuracy [and] promptness in all things.”

Pratt's list of Wall Street's six most important tools reflects this:

In 1903, Sereno Pratt stated the cornerstone of modern finance is “speed with accuracy [and] promptness in all things.”

Pratt's list of Wall Street's six most important tools reflects this:

(12/25)

We will focus on the ticker, however, the importance and growth of which is shown below:

"Ticker Impressions"

• 1890 - 7.2 Million

• 1901 - 12.8 Million

We will focus on the ticker, however, the importance and growth of which is shown below:

"Ticker Impressions"

• 1890 - 7.2 Million

• 1901 - 12.8 Million

(13/25)

Like the printing press, the explosion in information and data required further innovations and new systems to analyze / synthesize the data so that people could leverage it for their advantage.

One of the ways this data was distilled lives on today: Stock Tickers:

Like the printing press, the explosion in information and data required further innovations and new systems to analyze / synthesize the data so that people could leverage it for their advantage.

One of the ways this data was distilled lives on today: Stock Tickers:

(14/25)

This made it easier and faster to digest large quantities of information.

This image shows an early ticker tape reading:

This made it easier and faster to digest large quantities of information.

This image shows an early ticker tape reading:

(15/25)

Perhaps even more remarkable than the ticker, however, were the archaic systems in place *before* the ticker.

I present the "The High Frequency *Pigeon* Network"

Perhaps even more remarkable than the ticker, however, were the archaic systems in place *before* the ticker.

I present the "The High Frequency *Pigeon* Network"

(16/25)

Similar to the introduction of Book Reviews and Index sections following the Printing Press, Wall Street devised new systems to synthesize the vast quantities of data into actionable insights via two key developments:

• Market Slips

• Market Reports

Similar to the introduction of Book Reviews and Index sections following the Printing Press, Wall Street devised new systems to synthesize the vast quantities of data into actionable insights via two key developments:

• Market Slips

• Market Reports

(17/25)

For an investor, these services "saves him much of the trouble and time of analyzing reports and statements, and of interpreting movements."

(Pratt, 1903)

For an investor, these services "saves him much of the trouble and time of analyzing reports and statements, and of interpreting movements."

(Pratt, 1903)

(18/25)

Most interesting, was the way that savvy investors utilized this sudden boom in data to develop and back-test new sophisticated strategies.

Karl Karsten, a statistician and investor in the 1920s / 30s managed perhaps one of the world's earliest quantitative hedge funds.

Most interesting, was the way that savvy investors utilized this sudden boom in data to develop and back-test new sophisticated strategies.

Karl Karsten, a statistician and investor in the 1920s / 30s managed perhaps one of the world's earliest quantitative hedge funds.

(19/25)

With so much data to study and test, Karsten set out to see if he could determine what important "factors" influenced future economic conditions relying solely on data and a systematic approach (read: factor investing).

With so much data to study and test, Karsten set out to see if he could determine what important "factors" influenced future economic conditions relying solely on data and a systematic approach (read: factor investing).

(20/25)

I mean, just look how familiar his process sounds in relation to quantitative factor investors!

I mean, just look how familiar his process sounds in relation to quantitative factor investors!

(21/25)

As fellow financial history geek @jasonzweigwsj pointed out, Karsten developed a Long/Short Momentum fund utilizing what Karsten called "the hedge principle" (aka hedge fund).

As fellow financial history geek @jasonzweigwsj pointed out, Karsten developed a Long/Short Momentum fund utilizing what Karsten called "the hedge principle" (aka hedge fund).

(22/25)

Satisfied with his back-tested strategy for predicting the market's movements, Karsten launched a fund in 1930. Jason described it as

"A small fund run with real money and nothing but math."

Returns in the admittedly short period were good:

Karsten: 78%

Dow: -21%

Satisfied with his back-tested strategy for predicting the market's movements, Karsten launched a fund in 1930. Jason described it as

"A small fund run with real money and nothing but math."

Returns in the admittedly short period were good:

Karsten: 78%

Dow: -21%

(23/25)

Karsten theorized that as computing power and analytics improved over time...

“[There is] no reason why a very large machine should not be made for the simultaneous calculation of a large number of predictions of different phases of business and financial conditions”

Karsten theorized that as computing power and analytics improved over time...

“[There is] no reason why a very large machine should not be made for the simultaneous calculation of a large number of predictions of different phases of business and financial conditions”

(24/25)

Karsten's prediction sounds a lot like a section of @OSAMResearch 's Performance Hub on Canvas...

Karsten's prediction sounds a lot like a section of @OSAMResearch 's Performance Hub on Canvas...

(FIN)

Today we have more data than EVER. Technology has produced countless innovations, which requires more technology to synthesize and analyze this data for actionable intelligence.

OSAM's Custom Indexing Platform, Canvas, is one such critical tool.

canvas.osam.com

Today we have more data than EVER. Technology has produced countless innovations, which requires more technology to synthesize and analyze this data for actionable intelligence.

OSAM's Custom Indexing Platform, Canvas, is one such critical tool.

canvas.osam.com

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh