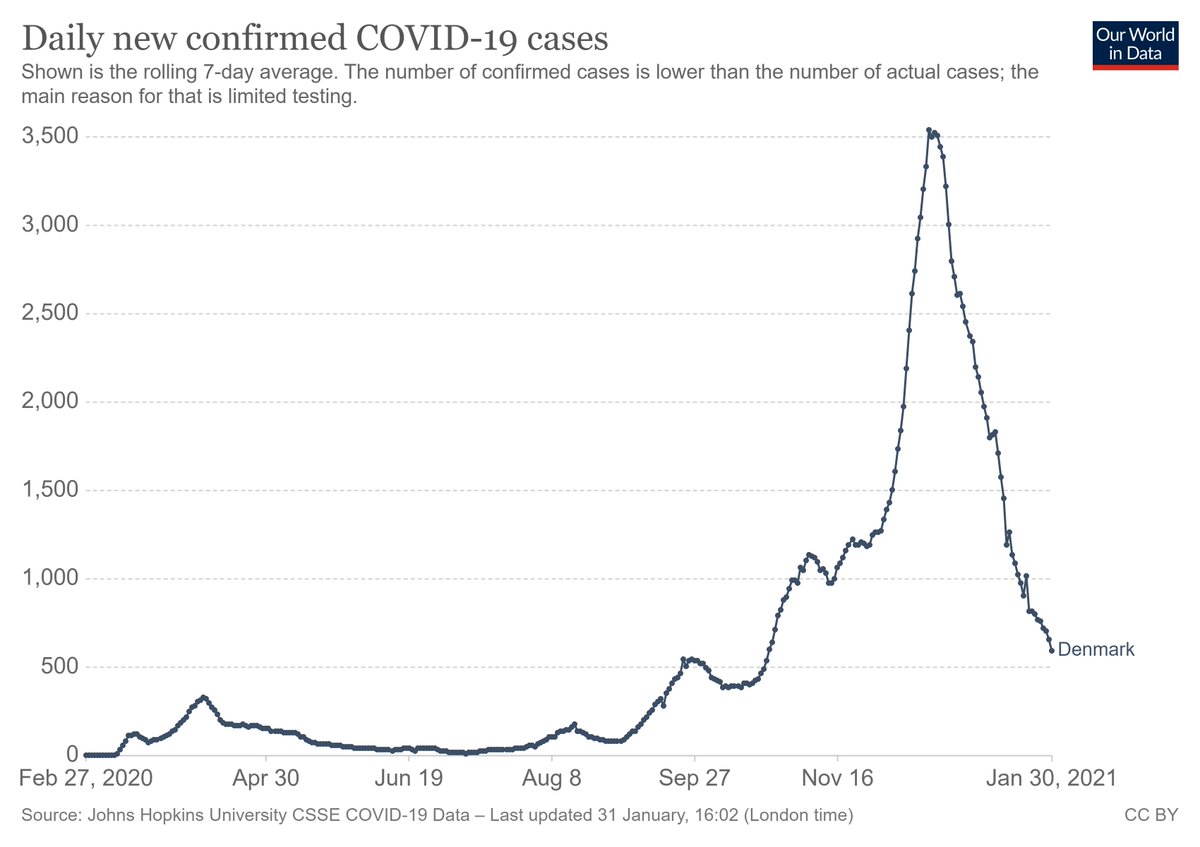

The B117 variant is now the dominant strain of SARS-CoV-2 in the UK, Ireland, Israel, Denmark. Likely also Portugal, Belgium, France, Italy, Norway.

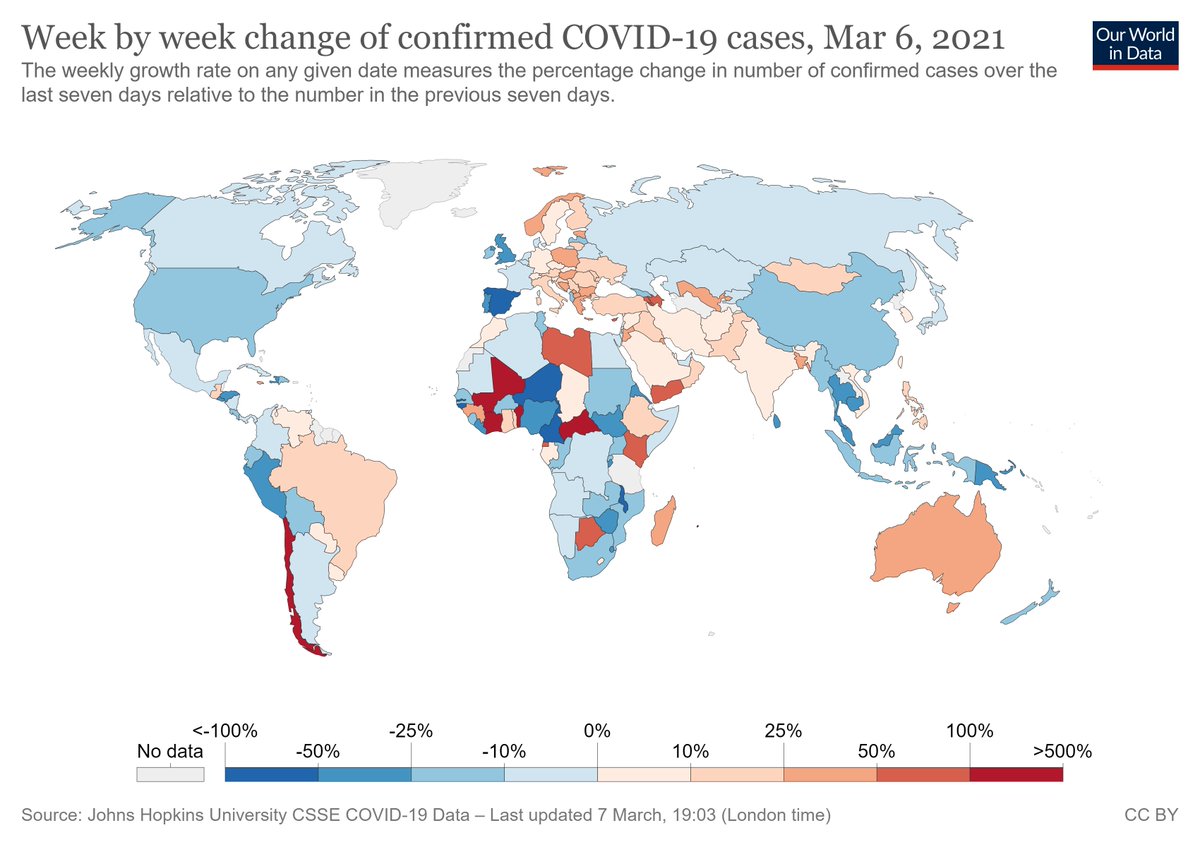

Yet for the most part, these are not the countries where COVID-10 cases are rising (see below). What gives?

Yet for the most part, these are not the countries where COVID-10 cases are rising (see below). What gives?

One explanation is that B117's transmission is being offset by restrictions, population immunity, etc. And that those countries w high B117 (UK, Ireland, Portugal) have locked down most. There is likely some truth to this - but not too much correlation w stringency index (below).

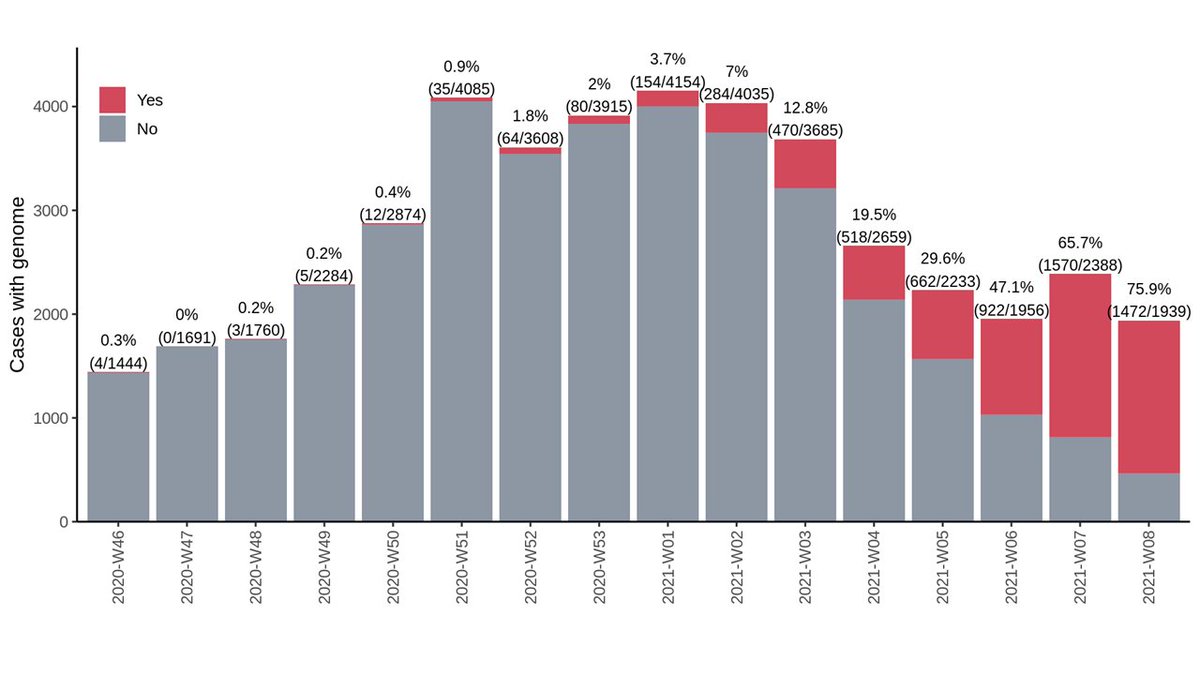

But it's also worth considering B117 and non-B117 COVID as separate epidemics. For example, look at Danish data below - it's tempting to think of B117 (red) as "replacing" non-B117 (grey). But that's not what's actually happening...

What's happening is 2 simultaneous epidemics, one of B117 and one of non-B117. (In reality, each new strain is its own epidemic, so it's more than just 2.) So it's arguably better to look at this as two separate epidemic curves. Viewed this way, B117 looks less scary.

If we estimate transmission of a variant that is gaining steam with one that is in decline, the new variant will look much more transmissible.

This is partially because the virus mutates to become more transmissible, but also because new variants take hold in new networks.

This is partially because the virus mutates to become more transmissible, but also because new variants take hold in new networks.

It's therefore difficult to compare transmissibility of a variant spreading in a new network to one that has been transmitting for a longer time.

It would be better to compare each variant at the same point in its epidemic curve - but those are at different points in time.

It would be better to compare each variant at the same point in its epidemic curve - but those are at different points in time.

But a key take-home message is that - at least right now - new variants do not seem to be fueling out-of-control epidemics in countries where they have taken hold.

This is good news.

This is good news.

In summary:

- The B117 variant is likely dominant in a large number of locations.

- These places aren't experiencing major surges of COVID-19 cases.

- We need to keep monitoring.

- But there is reason for optimism that we can manage the pandemic, even as new variants take hold.

- The B117 variant is likely dominant in a large number of locations.

- These places aren't experiencing major surges of COVID-19 cases.

- We need to keep monitoring.

- But there is reason for optimism that we can manage the pandemic, even as new variants take hold.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh