Umberto Eco: The Myth of Superman (1962)

Reprinted in Arguing Comics (2004)

#BooksAboutComics

Came across this article about Superman from Umberto Eco, and thought I would tweet out some excerpts and ideas.

Reprinted in Arguing Comics (2004)

#BooksAboutComics

Came across this article about Superman from Umberto Eco, and thought I would tweet out some excerpts and ideas.

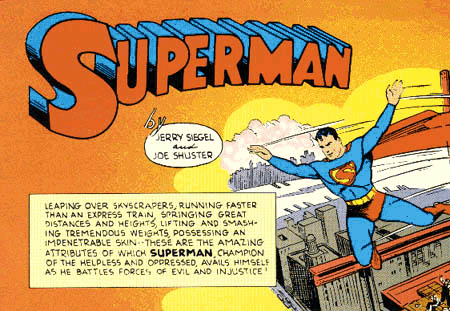

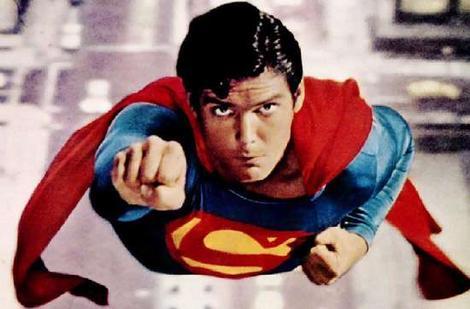

Eco first talks about heroes - equipped with superior powers, and those powers are often extremes of real abilities. That, in our modern world, man is sublimated to organizations and machines, thus our heroes embody powers to unthinkable degree we ourselves can not satisfy.

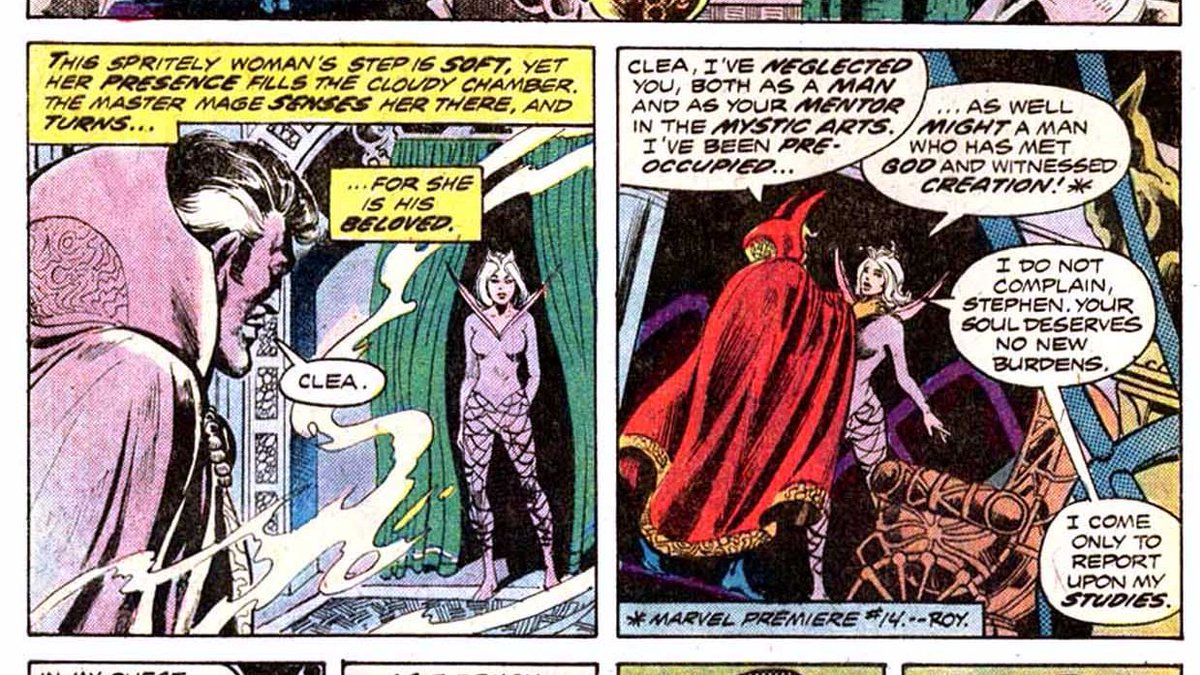

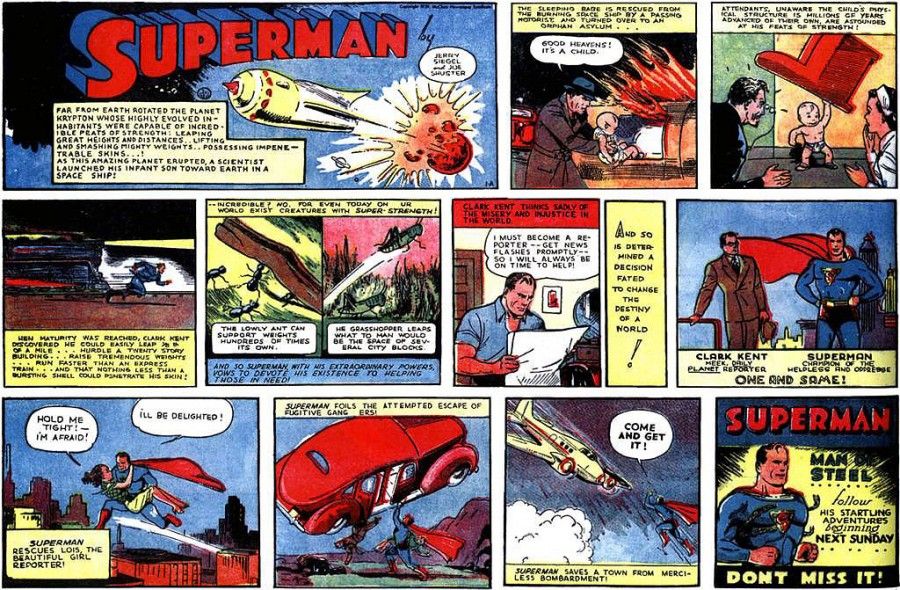

Superman has seemingly unlimited powers - of sight, hearing, strength, speed, etc. He is kind, handsome, and always helpful. Yet, he lives among us disguised a fearful, submissive Clark Kent - despised by Lois (who in turn, loves Superman)

"In terms of narrative, Superman's double identity allows the suspense characteristics of a detective story and great variation in the mode of narrating our hero's adventures, his ambiguities, his histrionics"

"From a mythopoeic point of view, Clark Kent personifies the average reader, harassed by complexes and despised by his fellow men."

(So much for Marvel comics originating Heroes with Flaws - its right here with Superman)

(So much for Marvel comics originating Heroes with Flaws - its right here with Superman)

Chapter1: Here Eco points out how traditional myths are stories of the past. The characters had traits, they had a story. Hercules has a story, which has already taken place. Roland has a story. You can add or embellish it, but the tale is the tale.

The modern novel transfers the readers interest to what will happen. The events are happening as events are being told. What is lost, says Eco, is the character's mythic potential. What is gained, is a universality.

"The mythological character of comic strips must be an archetype, the totality of certain collective aspirations, and therefore immobilized in an emblematic and fixed nature that renders him easily recognizable but ...

"but since he is marketed in the sphere of a 'romantic' production for a public that consumes 'romances,' he must be subjected to a development which is typical of novelistic characters." - Eco

So, both frozen but changing somehow

So, both frozen but changing somehow

Chapter2: On plots and 'consumption' of the character

Eco tells us a tragic plot is a series of events ending in catastrophe. A novelistic plot becomes a continuous se ries that must proliferate ad infinitum. The Three Musketeers becomes 20 Years Later and on again...

Eco tells us a tragic plot is a series of events ending in catastrophe. A novelistic plot becomes a continuous se ries that must proliferate ad infinitum. The Three Musketeers becomes 20 Years Later and on again...

"...the greater the capacity to sustain itself through an indefinite series of contrasts, oppositions, crises, and solutions, the more vital it seems." - Eco

(more later)

(more later)

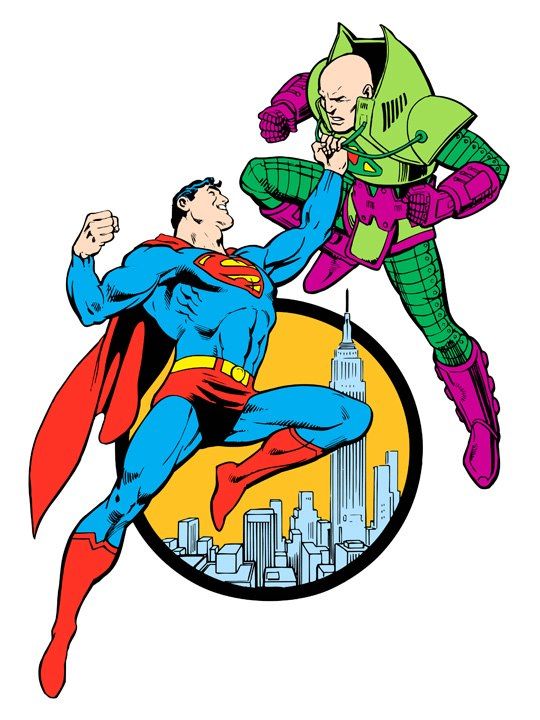

Superman, says Eco, is so powerful that nothing impedes him, and therefore there is no development. So, a weakness, Kryptonite, is created, but as a narrative theme it doesn't have much promise and needs to be used sparingly.

Which then, continues Eco, leads to putting Superman into weird situations. Cunning evil scientists, diabolical aliens, imaginary stories, magical imp Mxyztplk, etc.

Nonetheless, Superman wins through. Eco now introduces an idea of 'consumption'. That by doing something, Superman has added to his list of accomplishments, and taken a step toward death. He has aged, if only a bit. In this way, Superman is being consumed.

So this is an idea we comic nerds know well, although we didn't use the term 'consumption'. Comic books have long had 'appearance of change', or 'sliding timescales' or even reboots (large and small). That continuity implies consumption!

Now Eco goes on to say Superman *doesn't* consume himself up with adventures. He is "inconsumable". A classic hero, like Hercules, is also incomsumable, but for a different reason. Hercules is already fully consumed. (or a myth that is tied to rebirth or seasonality)

Superman is different. He is incomsumable but in the present, not the past. Superman is a paradox. He is like us, tied to our conditions of birth, life and death, but inconsumable - where we are. Yet he is not a god, but a man - whom we identify with.

So Superman is both consumable (to be like us) but incomsumable. Timeless, but accepted because his activities take place in our world (more or less) and is like us. Its a narrative paradox.

To solve this narrative paradox - of Superman being both one of us mortals, living in the here and now, but also timeless. Doing things, but not consuming time in doing them. The paradox needs a paradoxical solution.

(more later)

(more later)

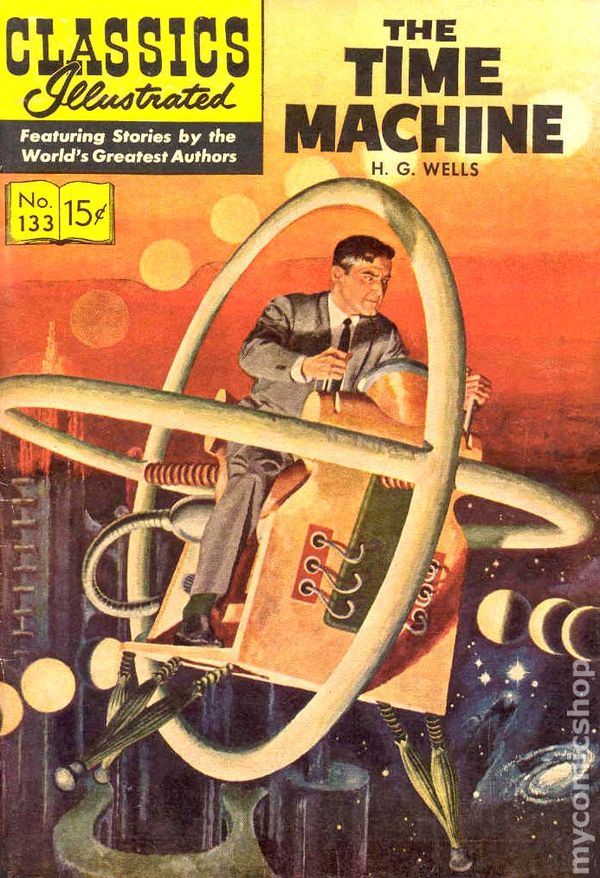

Chpt 3: Temporality

At this point Eco goes into a discussion on Time.

Aristotle: Time is the amount of movement from before to after. We need a 'preceeding' and a 'follows'. Causality, or what we comic nerds call Continuity.

At this point Eco goes into a discussion on Time.

Aristotle: Time is the amount of movement from before to after. We need a 'preceeding' and a 'follows'. Causality, or what we comic nerds call Continuity.

Without causality (or continuity) there is no responsibility; no situation is grave, no decision difficult. We need actions and decisions to have consequence - to be part of a string of causality.

Yet the narrative structure of Superman evades this to avoid being consumed.

Yet the narrative structure of Superman evades this to avoid being consumed.

Chpt 4: Plot Not Consuming Itself

So in Superman, "The very structure of time falls apart, not in the time *about which*, but, rather, in the time *in which the story is* told" - Eco

What breaks down is what ties one story to another

So in Superman, "The very structure of time falls apart, not in the time *about which*, but, rather, in the time *in which the story is* told" - Eco

What breaks down is what ties one story to another

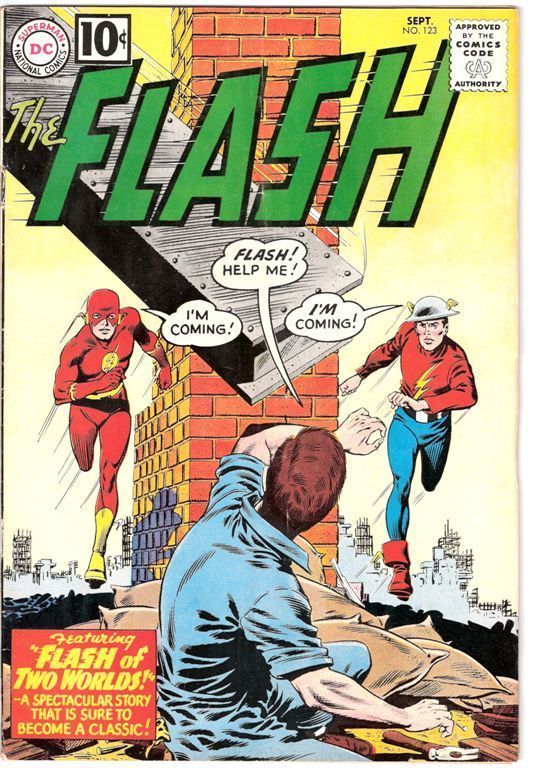

Superman concludes one adventure. A new story begins *but not where the last one ended*. If so, he would aged, consumed himself, taken a step in his mortal journey. So, the new tale is unhinged from the preceding.

But even by 1962, this hits the "Little Orphan Annie" problem. How long can you be a disaster-ridden child? How many decades can you pull that off without it being comical?

"Superman's scriptwriters have devised a .... oneiric (dreamlike) climate ... where what has happened before and what has happened after appear extremely hazy" - Eco

So we get Fuzzy Continuity.

So we get Fuzzy Continuity.

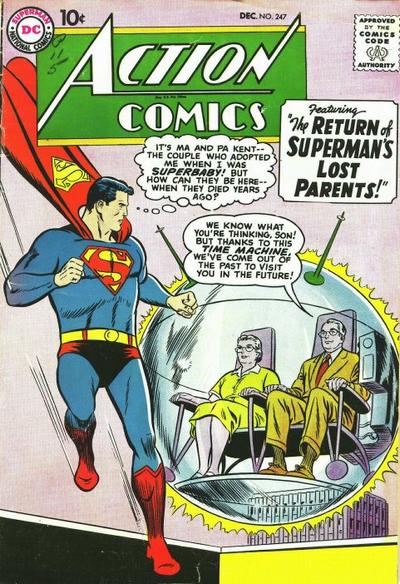

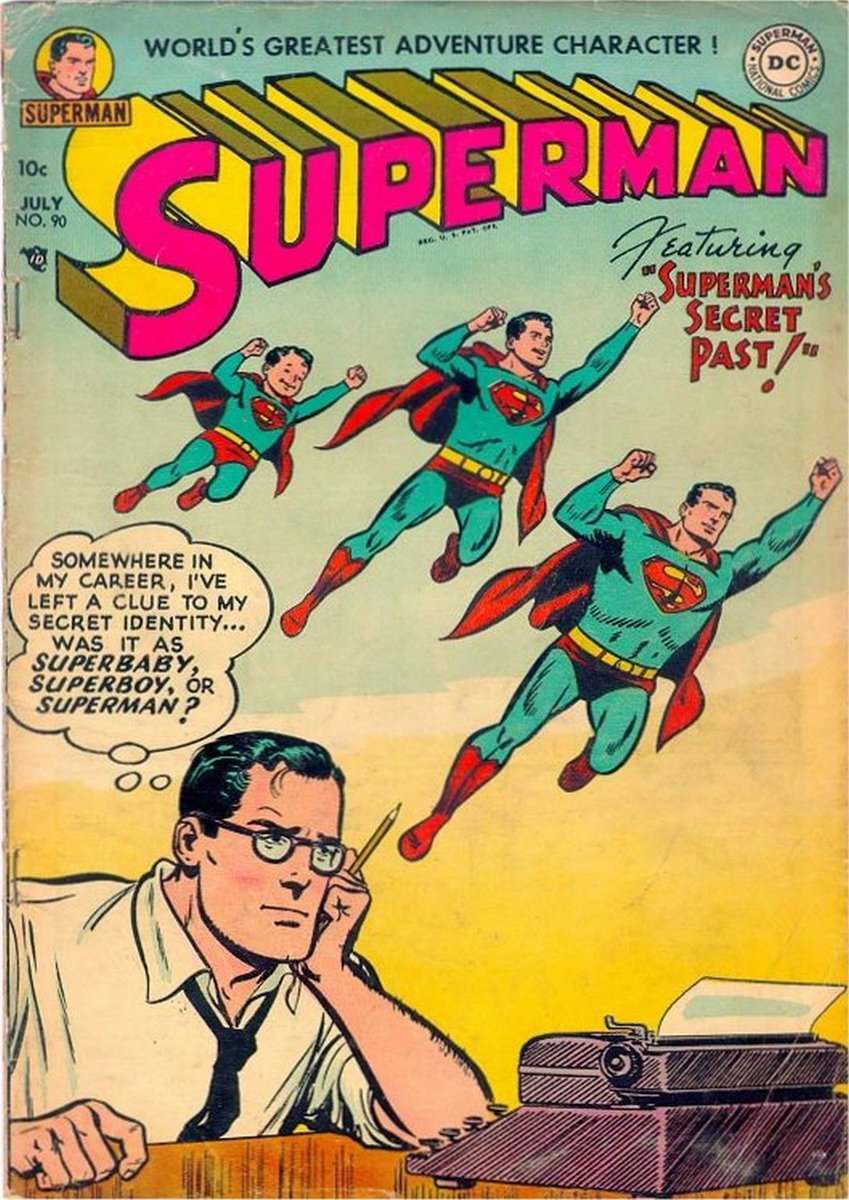

As the Superman mythology grew - to include Superboy, Superbaby, Supergirl, etc - the events about Superman are retold to take into account this hitherto not mentioned character or stage.

Superman's scriptwriters hit on the idea of the Imaginary Story. A story in which the readers approval is deferred Now you can explore decisions to marry Lois, or Lana, and explore that without consuming the character in time.

Sidebar: Eco here comments on Roberto Giammanco's remarks on the consistently homosexual nature of characters like Superman and Batman. Eco agrees on Batman, but sees Superman more as Parsifalism, or mythic chastity.

Sidebar2: Superboy collaborates with a Legion of Super-Heroes that are teenagers, usually ephebic but of both genders. Superman works cheerfully with Supergirl, and reacts like a bashful schoolboy in a matriarchal society to the advances of Lois and Lana (paraphrasing Eco)

Sidebar3: This is what makes the mermaid, Lori Lemaris, interesting. She can offer Superman only an underwater menage, a paradisiacal exile that Superman must refuse out of a sense of duty elsewhere.

So Superman is chaste. His relationships mostly platonic.

So Superman is chaste. His relationships mostly platonic.

By and bpy, Superman's parsifalism aids in his not being consumed by either romantic or erotic ventures.

And like that, maybe Superman become a tragic figure for you. A life without romance or carnality. The Last Son of Krypton indeed.

And like that, maybe Superman become a tragic figure for you. A life without romance or carnality. The Last Son of Krypton indeed.

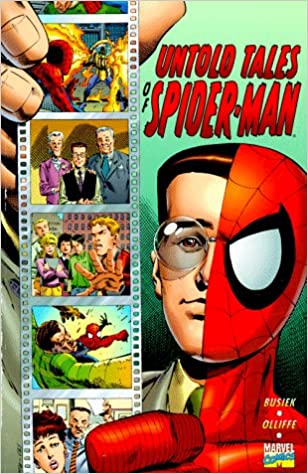

And so Superman of this time had many Imaginary Stories. Another variant are Untold Tales, going back into that hazy continuity and adding something, or reworking things. Nothing is consumed (and nothing is really gained, I might posit)

"In this massive bombardment of events which are no longer tied together by any strand of logic, whose interaction is ruled no longer by any necessity, the reader loses the notion of temporal progression" - Eco

More Echos of Eco on Superman (1962) later.

I think there was a more elegant way of fixing my thread, but that is so annoying when the rivers bifurcate.

I think there was a more elegant way of fixing my thread, but that is so annoying when the rivers bifurcate.

To finish up this thread, it goes "Full Umberto Eco" with lots of philosophy. In part, he explores the iterative scheme where characters each new adventure has the same virtual beginning, divorced from the past, following a similar path, and readers attain enjoyment that way.

Eco uses cozy mysteries to explore the iterative scheme, going into depth using Nero Wolfe as an example of how each adventure follows a formula. Readers gain pleasure in knowing the beats and while the climax has some uncertainty, its form is known from the beginning.

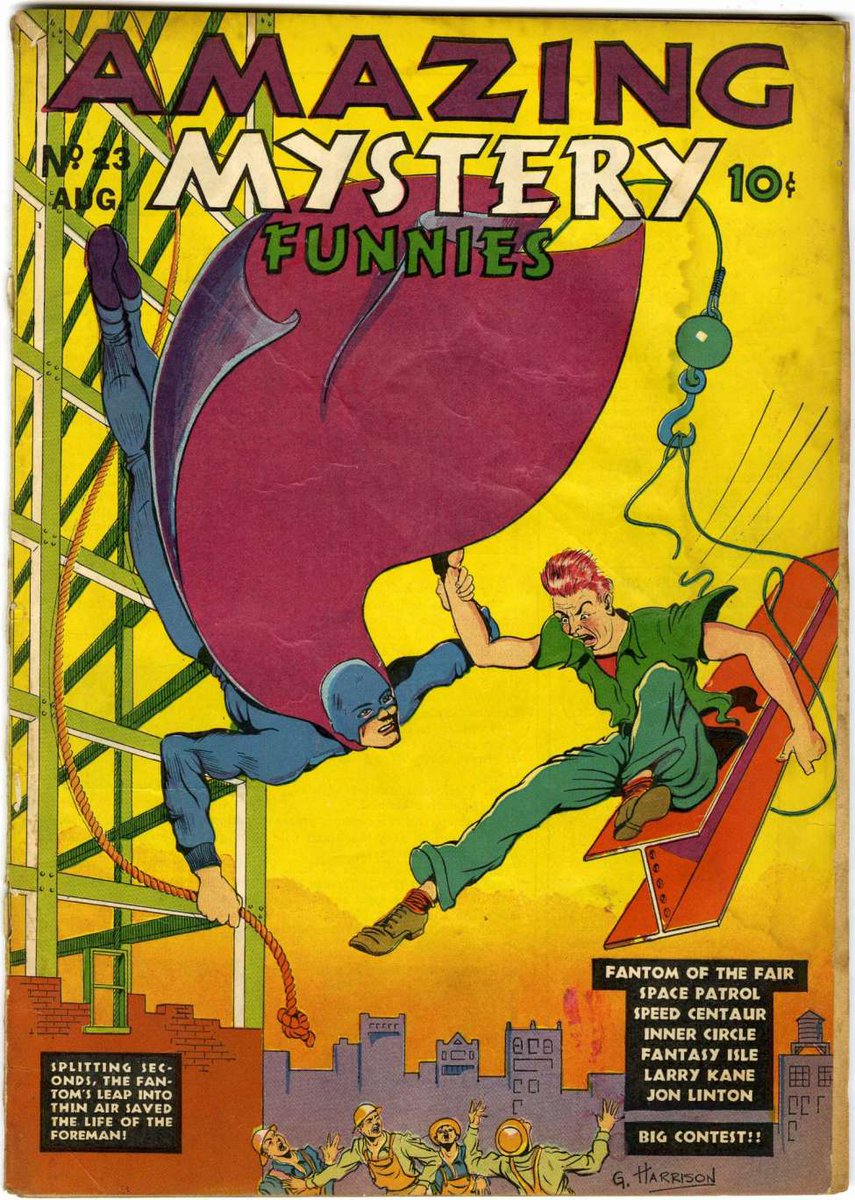

Eco notes how this narrative structure - the iterative one - can be traced back to the French Fantomas, perhaps the first inexhaustible character.

Eco calls this a 'high redundance message', one that keeps hammering away at the same meaning we got in issue 1.

Eco calls this a 'high redundance message', one that keeps hammering away at the same meaning we got in issue 1.

"Paradoxically, the same detective story that one is tempted to ascribe to the products that satisfy the taste for the unforseen is, in fact, read for exactly the opposite reason - an invitation to what is taken for granted, familiar, and expected" - Eco

Which does seem to apply to Superman and most comic book characters. Perhaps we don't know the villain, or how the hero will triumph, but those are 'accessory elements'

Is this in better evidence than in Columbo? We know from the beginning WhoDunnit. All the enjoyment is in the familiar redundant beats, and how we love to watch our hero in combat (metaphorically) with a worthy opponent. But the end is preordained.

Its fun with redundancy

Its fun with redundancy

Why do we enjoy this redundant scheme?

"Narrative of a redundant nature would appear in this panorama [of a continuous load of information, often by jolts, causing continuous mental reassessment and stress] as an invitation to repose, the only occasion of true relaxation" - Eco

"Narrative of a redundant nature would appear in this panorama [of a continuous load of information, often by jolts, causing continuous mental reassessment and stress] as an invitation to repose, the only occasion of true relaxation" - Eco

"Is it not natural that the cultured person should, in moments of relaxation and escape (healthy and indispensible) tend toward triumphant infantile laziness and turn to consumer product for pacification in an orgy of redundance" - Eco

Eco was writing in 1962, but it provides insight into the common refrain of

"Get Your Politics Out Of My Comic Books"

and the ample evidence that there is often politics in comic books, or that some comic books can be seen with a definite political POV.

"Get Your Politics Out Of My Comic Books"

and the ample evidence that there is often politics in comic books, or that some comic books can be seen with a definite political POV.

The usual retort to "Get Your Politics Out Of My Comic Books" is that it is a one-sided complaint meant to curtail one kind of messaging, but not curtail its antithesis.

However, Eco pens a defense of pure escapism

However, Eco pens a defense of pure escapism

"As soon as we consider the problem from this angle [an escape], we are tempted to show more indulgence toward escape entertainments (among which is included our myth of Superman), reproving ourselves for having exercised an acid moralism on something beneficial" - Eco

"The problem changes according to the degree to which pleasure in redundance breaks the convulsed rhythm of an intellectual existence based on the reception of information and becomes the norm of every imaginative activity" - Eco

Eco concludes his essay with a discussion on civic responsibility in superheroes.

Superman, and many others, could take over governments or alter the world. They don't, and, on the plane of childrens literature, is a moral story of good over evil.

but "What is Good?"

Superman, and many others, could take over governments or alter the world. They don't, and, on the plane of childrens literature, is a moral story of good over evil.

but "What is Good?"

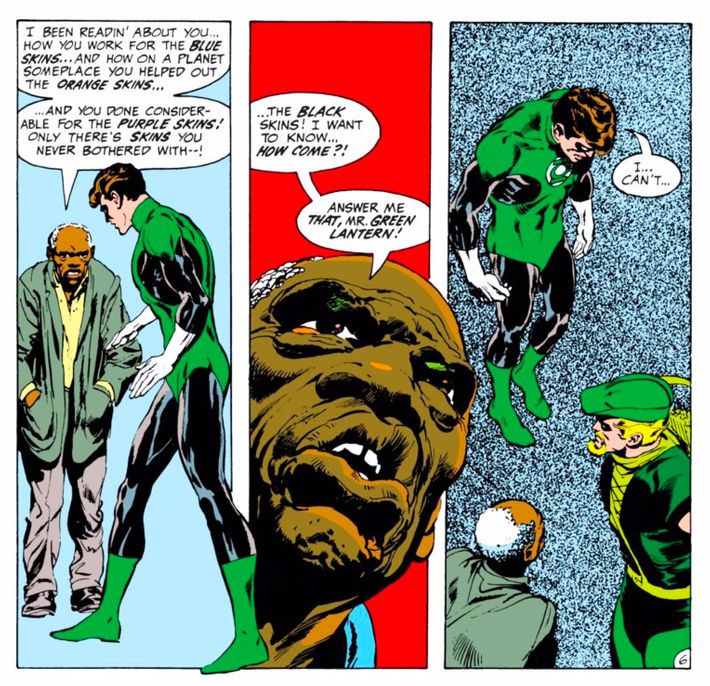

Superman and others could end hunger? Eco says Superman could liberate six hundred million Chinese from the yoke of Mao? (we might think of North Korea).

But Superman doesn't do those things. He might on some other world, but not on Earth.

But Superman doesn't do those things. He might on some other world, but not on Earth.

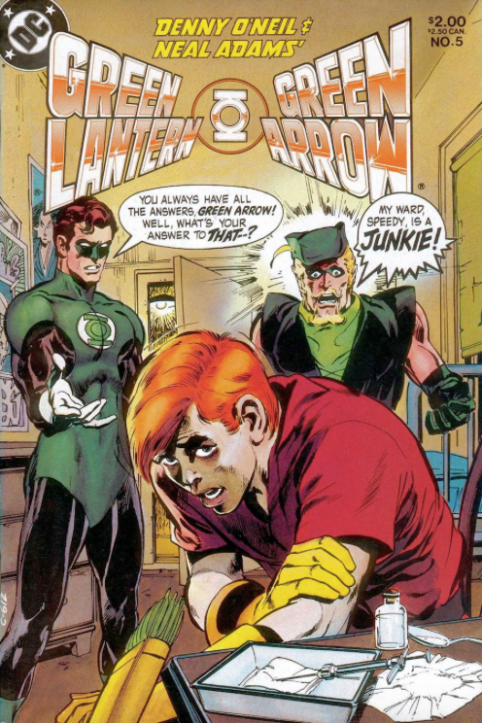

This came a decade after Eco's essay, but its essentially asking the same question.

If comic books are Good Over Evil, then maybe we should spend some thought on "What is Good?"

If comic books are Good Over Evil, then maybe we should spend some thought on "What is Good?"

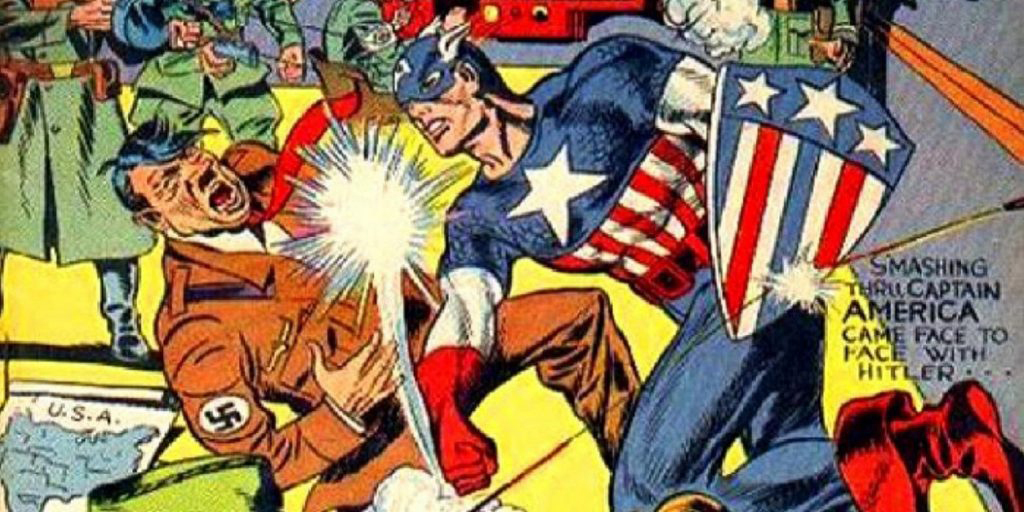

If you read old comic book or comic strips with superheroes, you will see this idea of "What is Good/Evil" shifting.

There are times when it seems like Superman only fights thieves and robbers, but other times other evils are taken into account.

There are times when it seems like Superman only fights thieves and robbers, but other times other evils are taken into account.

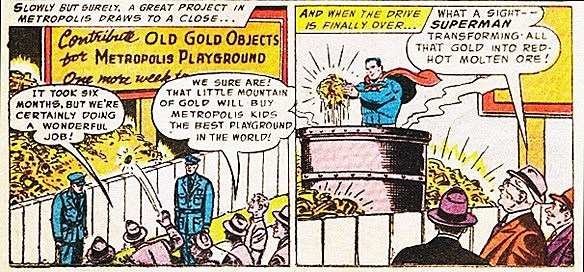

Eco completes Superman's morality with Good being mostly about charity. Superman could use his energy to directly produce riches, but instead does things like charity drives.

These small scale views go hand in hand with the redundant plots and keeping Superman inconsumable.

These small scale views go hand in hand with the redundant plots and keeping Superman inconsumable.

So that was Eco on The Myth of Superman from 1962

Hope you enjoyed it. It is the kind of meandering thread I like to do on Twitter.

Hope you enjoyed it. It is the kind of meandering thread I like to do on Twitter.

@threadreaderapp please unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh