We analyzed data on 1,127 killings by police in 2020 - finding alternative responses to mental health, traffic violations and other non-violent situations could substantially reduce fatal police violence nationwide. A thread (1/x). policeviolencereport.org

Working with an incredible team of data analysts (h/t @moncketeer @MaryLagman @KirbyPhares @backspace), we compiled media reports, official statements and other info on how each incident began, what reportedly happened during the encounter and whether officers were charged.

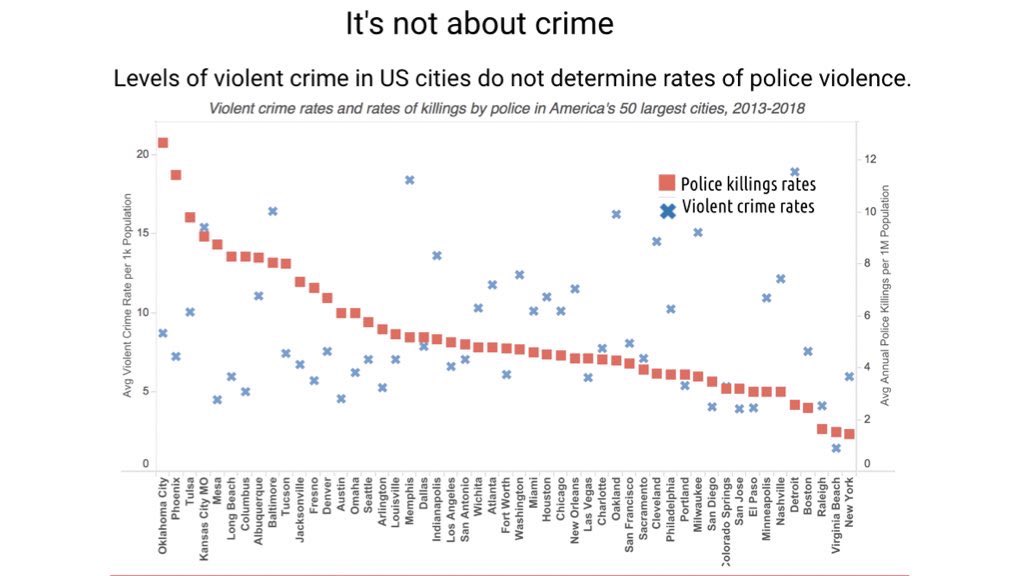

First, 2020 was largely in line with a longstanding pattern of ~1,100 killings by police per year since at least 2013. The lockdown, economic crisis, changes in crime, etc didn’t appear to change this trend, the overall pace of fatal police violence in America.

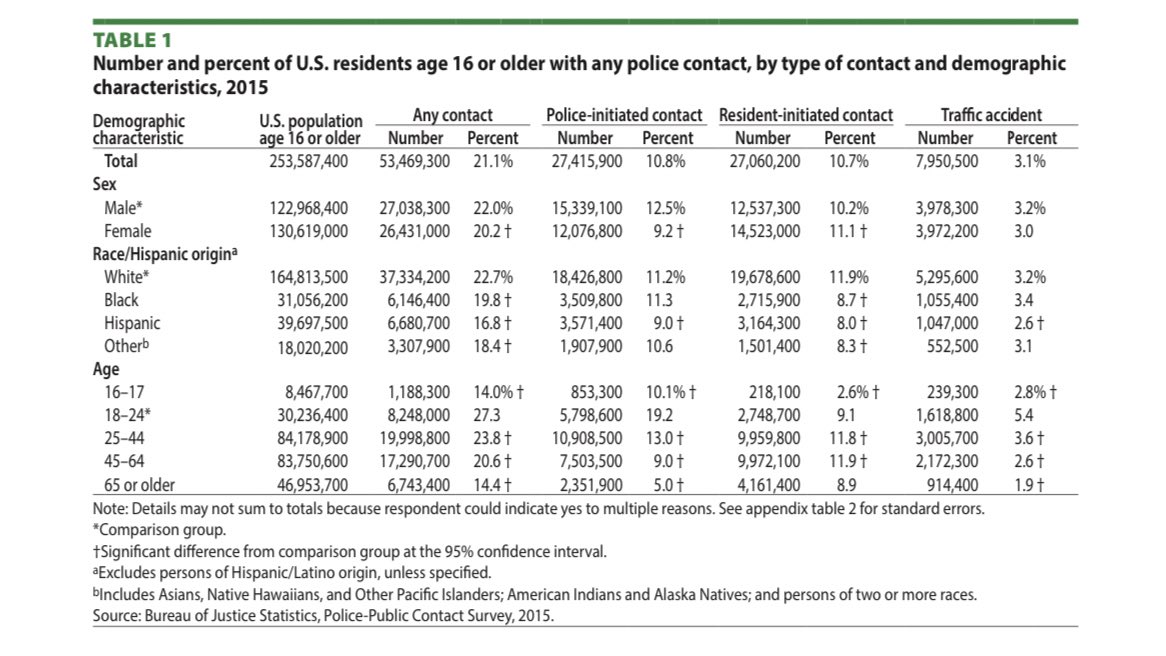

Racial disparities in fatal police violence in 2020 were also clear and consistent with past years - Black people were killed by police disproportionately and were more likely to be unarmed when killed.

The majority of people killed by police in 2020 were killed after being stopped for an alleged traffic violation, disturbance, mental health crisis, other reportedly non-violent offense, or in situations where no crime was reported or alleged (car accident, wellness check, etc).

The initial 911 calls can differ from what happened after police arrived. Arrival of police often escalates the situation- e.g. turning a mental health/wellness check into a barricade situation. Proven alternatives to police should respond to these calls: usatoday.com/story/news/nat…

Last year, police killed 121 people after pulling them over for a traffic violation. Cities like Berkeley are moving towards a model that removes police from traffic enforcement, which could save lives. theappeal.org/traffic-enforc…

Colorado is considering legislation (SB21-062) prohibiting police from arresting people for misdemeanors, traffic violations and other low level offenses. 80% of all arrests. This could impact a huge number of cases where police currently use deadly force. leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/…

And, just like past years, only 1% of cases where police killed someone in 2020 have led to officers being charged with a crime. The murder of George Floyd was one of only 16 cases where officers were charged last year.

We were able to identify the officers by name in 444 of the 1,127 killings by police. Based on media reports, at least 14 cases involved officers who had shot or killed someone before and 5 of those officers had shot or killed multiple people before.

Statewide restrictions on police personnel records prevent the release of officer’s past misconduct history in all but 13* states.

*NY became the 13th state after repealing 50-a. project.wnyc.org/disciplinary-r…

*NY became the 13th state after repealing 50-a. project.wnyc.org/disciplinary-r…

In the states where this information is publicly available, the worst officer is Officer John Nobles of Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office. Killed Leah Baker last year in his *5th police shooting*, including killing a 16 year old child in 2015. He’s still employed as an officer today.

Removing police from traffic enforcement and mental health calls could impact nearly 1 in 5 killings. If police responded to remaining situations without killing people who were not allegedly threatening officers or civilians with a gun, police killings could be reduced 55-60%.

And that’s a conservative estimate based on info that has been released publicly, often by the police without video evidence. We’ve seen police overstate a “threat” or cover up details to exonerate themselves. The actual impact of alternatives/changes would likely be even bigger.

Learn more, download all the data, take action at policeviolencereport.org

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh