Every week throughout #WomensHistoryMonth, we'll be passing the mic to someone from the @NatGeo family who will be highlighting an aspect of women's history or their work. Today we're hearing from Nat Geo Explorer and Multimedia Storyteller @LillygolS. 1/35

Hi everyone! My name is Lilly Sedaghat and I’m a Nat Geo Explorer & Multimedia Storyteller. I share stories to connect people to the planet, the systems we’re a part of, and the cultures that make life beautiful and diverse. 2/35

Today, I want to take you on a journey 800 miles south, with just a bike and a backpack, to explore the narrow boundary between nature and humanity, climate change and COVID. 3/35

This year, COVID rocked our world. With it came great loss, uncertainty, change. To make sense of things, I needed to go out and understand things for myself. 4/35

With my partner Cory, we began a journey that took us through 33 communities, 12 counties, 7.8429° of latitude, four climatic regions, two states, and a single divided nation. 5/35

We weren’t bike people. We were breakdancers, storytellers. Bike touring? It was our first time. 6/35

But it felt necessary. How could we tell a story about the changing planet without experiencing that change ourselves? 7/35

To feel it intimately, in the outdoors, watching the horizons change and the landscapes shift, moving in and out of diverse communities united by the experience of this climatic shift. 8/35

For 6-8 hours a day, we were on our bikes—riding through forests, on the edge of steep cliffs and the shoulder of single-lane highways—exposed to the elements, the wind currents from speeding cars, the loud horns of RVs and transport trucks. 9/35

There was often no wifi, with some stretches of road devoid of food or drink for 30 or more miles. Our bodies were the only things that propelled us forward. We were our own energy. 10/35

It was the closest I’ve ever felt to being biologically human, and the closest I’ve ever been to understanding climate change. 11/35

60 miles on the first day took us straight into Netarts Bay, a small oceanside community famous for its oysters and clams. 12/35

The bay is a well-mixed estuary—the river empties into the sea; salt water mixes with freshwater, and salinity levels are constant from top to bottom. odfw.forestry.oregonstate.edu/freshwater/inv… 13/35

In 2006-2008, oyster larvae began to die in rapid numbers. Ocean acidification—the absorption of CO2 from the atmosphere into the water—makes it difficult for them to form the shells they need to survive. e360.yale.edu/features/north… 14/35

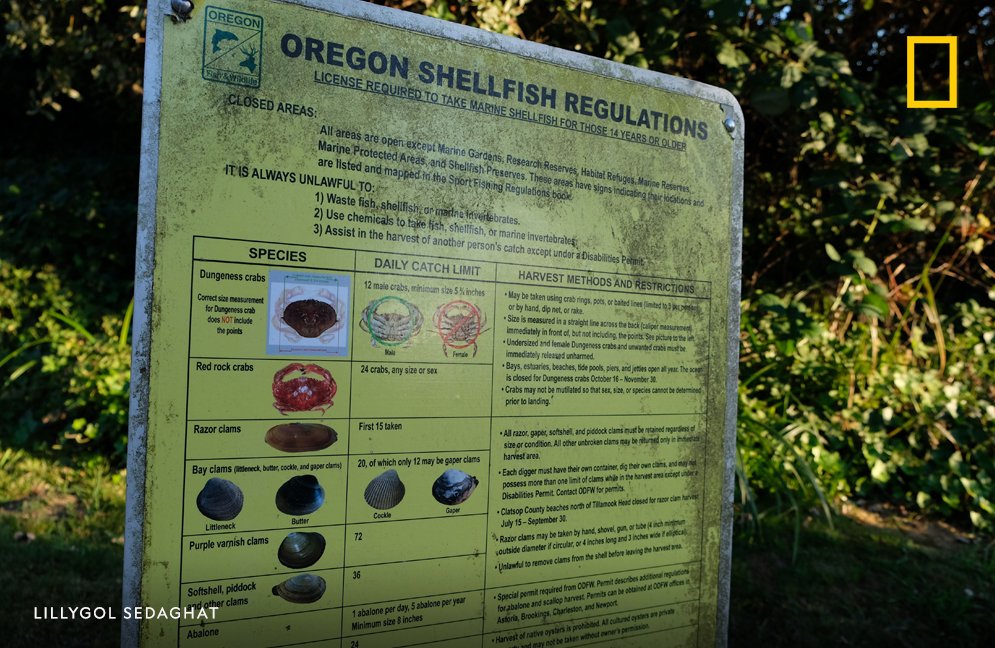

We looked at the wind-battered sign detailing state rules for the daily catch. Small boats were on the water. We could make out buckets and nets, boots and overalls. It all felt so quiet. 15/35

This was a story of adaptation, of how to support a multi-million dollar industry and a local way of life through careful chemical controls in light of a changing ocean. 16/35

As we rode out the next day, we waved at the local fishers, our hands numb with the morning cold. I felt like change here was happening quietly, subtly, over time, and so we must too, to preserve what matters. 17/35

The concept of change followed us everywhere. We moved from Oregon to California, from clear coasts to wildfires. Everyday we had a set path, and everyday, we had to adjust and adapt to the reality before us. 18/35

That week, the sky oscillated from an apolycatic yellow to a dull gray. 1,000,000 acres burned. 40,000 people fled their homes. And that was just in Oregon. storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/6e1e42… 19/35

We had a decision to make: do we stay or do we go? Continue forward or call it quits? We checked the air quality maps. Reds and purples flashed PPM levels, warning of hazardous conditions. gispub.epa.gov/airnow/ 20/35

We chose to keep biking, to see the journey through. And somehow, we made it. The winds changed, the firefighters risked their lives; we held onto the hope that everything was going to be okay. 21/35

That hope continued to be challenged then restored, lost then fortified, with the story of one Pomo Native American woman and her fight to preserve Pomo culture against the backdrop of climate change. 22/35

We saw Bernadette dancing in a parking lot, the doors to her blue pickup open, salsa music blasting. She and her partner laughed as they missed a spin. 23/35

We ended up eating at the same Thai restaurant; chili-streaked noodles and three empty tables stood between us. The social distance didn’t prevent conversation. 24/35

Slowly, she opened her world to us. For the Pomo, land is their source of life, a source of physical strength and spiritual connection. Nature is an essential part of who they are. suantianstories.com/post/day-19-pa… 25/35

But climate change is putting that identity at risk, particularly with one of their most staple foods—the acorn. 26/35

Acorns grow on Chishkale, also known as tan oak trees. But these trees have been dying due to sudden oak death, an airborne pathogen, and rising temperatures are expected to increase the spread. nrs.fs.fed.us/pubs/gtr/gtr-n… 27/35

As I sat there and listened, I wondered what would happen if the thing I relied on for subsistence, the thing that formed the basis of my identity, slowly disappeared. This was a story of loss as much as it was about renewal. 28/35

Bernadette taught me that you must move, take action, actively try to preserve & educate, heal & communicate. 29/35

Her dance, a blend of traditional Pomo style & modern movements, is a direct result of that—preservation as an act of movement; movement as an act of adaptation. lindamaigreen.com/chishkale (Video by @omg_lmg) 30/35

When we crossed the Golden Gate Bridge into San Francisco, I looked back to marvel at what we had accomplished. 800 miles. 2.5 weeks. Over 50,000 ft of elevation gain. Cars zoomed on either side. Horns blasted, engines roared. Everything, everyone seemed to be in motion. 31/35

Underneath all the movement was the road, the bridge—the infrastructure that connected one side to the other, nature to society. 32/35

In that moment, I realized that we needed the road to guide us to where we wanted to go. We needed the bridge to connect us to one another, to create access between people and place. 33/35

Both require maintenance, or else they collapse. And in this regard, both represent our planet and the way we need to live and maintain it. 34/35

The journey of humankind is the journey of how we live on planet earth. How we navigate, connect & co-exist in a limited space with limited resources. But it's the greatest—and most difficult—of journeys and one we all have a role in contributing to. suantianstories.com 35/35

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh