When we talk about Industrial Mobilization for WWII, we mean the ability to produce, and the actual production of, weapons, ammunition, equipment, and other wartime needs. Globally, much of this occurred from 1938 to 1945. The US was a little late to the game.

The US government authorized a series of public works planning efforts in 1933 in an effort to create jobs and help the country survive the Depression. An unexpected benefit of this effort was the development of enterprises that the Army could later utilize for production.

Army planners realized that future planning could incorporate the possibility that personnel would be available in greater numbers than previously during peacetime. They began estimating future needs even if the capabilities to meet them did not yet exist.

In November of 1933, a “Policy for Mechanization and Motorization” was drawn up and supported by the G4 who expressed that the War Department “could not be content” with partially equipping the first million men in the Initial Mobilization Plan.

This helped push the idea of equipping certain types of units to ensure a balanced force was initially available should a war break out. As we’ll see throughout the series, many of these concepts evolved over the last 80+ years and can still be found in the modern @USArmy

One of these projects was the 105mm howitzer, which became the principal weapon of artillery in an infantry division, replacing the 75mm gun. George C. Marshall did not want to fully replace the 75s yet since there was a shortage of funding available for new stuff. @WWIImuseum

GEN Marshall wanted to use funds for equipment that he knew needed replacing, but he was also hesitant to replace the 75s with the 105s just yet because of the large amount of 75mm ammunition we already had.

The first purchase of 105mm ammunition cost $192,200,000.

But industrial mobilization is not just about the production of equipment and weapons and other military things. The modern United States benefits from a pretty massive defense industry; that was not the case during this time before WWII.

The industry we did have would need to be converted to produce military equipment. They would need to adapt their skills to fit production for wartime needs. They would need to learn what those wartime needs are. And they would need money and resources to make it happen.

From about 1938 until 1942-ish, the UK led the effort to coordinate industry and resources around the world. And they did this while fighting from the very beginning of the war, which actually bought the US and others time to mobilize before joining the fight. @LeavenworthThe

In 1941, government spending made up about 30% of the US GDP and by 1944 that had been increased to reach about 79% GDP. To help support things like war spending, taxes increased significantly as well. We also had war bonds and other programs, but we can talk about those later.

So, war is expensive. But in the short term, war can be good for the economy.

Secretary of War Harry Stimson said in 1940: “If you are going to try to go to war, or to prepare for war, in a capitalist country, you have got to let business make money out of the process or business won’t work.”

The processes needed to convert the civilian industry to a wartime industry were slow throughout the 1939 to 1941 period.

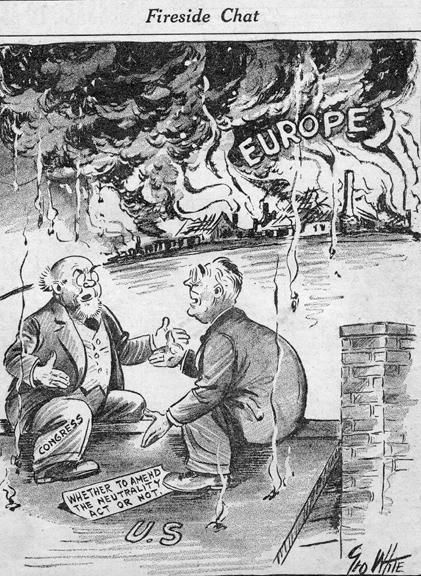

Congress was relatively conservative with spending and with the isolationist sentiment throughout the country, it was going to be an uphill battle with our selves as a nation just to get things done.

Defense contracts helped. During WWII, US unemployment dropped from 14.6% in 1940 to less than 2% by 1945. About 1/5 (20%) of the population found work within the defense industry and armed forces.

As mentioned, the UK was pulling a lot of the weight coordinating global resources and industry from 1938 until about 1942.

Early in 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Lend-Lease Act, which gave the UK access to the “arsenal of democracy” the United States possessed. By the middle of that year (1941), FDR was pushing for more extensive wartime preparation efforts, hoping we had the time.

If you're just tuning in or you've missed any of the previous threads, you can find them all saved on this account under ⚡️Moments or with this direct link twitter.com/i/events/13642…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh