Today in Investment Law and Policy, we discussed "Investment Law in Developing Countries.” This is a problematic category, but the framing allows us to discuss important questions like law-makers vs. law-takers, and the effect of investment on local & indigenous communities. 1/

The idea of classifying the world as “developed” and “developing” is problematic and there’s no one way to do it. I started, very crudely, with this map from @worldbankdata, classifying countries by per capita GNI. Like I said, very crude, but keep this image in your mind. 2/

Now this is a map of investment treaty programs by “coherence,” put together by @w_alschner & Dmitriy Skougarevskiy. The darker the shade, the more coherent a country’s BITs, meaning, roughly speaking, the more each treaty resembles all of the others. 3/

These two maps overlap in many ways: the wealthier countries tend to be the "law-makers," the drafters of treaties, while the lower-income countries are often "law-takers." There are outliners—India, Mauritius, N. Korea—and those tell interesting stories, too. 4/

But why would developing countries agree to be law-takers in this way? What’s in it for them. In Andrew Guzman’s terms, why do “LDCs sign treaties that hurt them?” 5/

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

@JBonnitcha @laugepoulsen @WaibelM09 demonstrate that countries’ reasons for signing BITs, esp. in the 1980s and 1990s, reflected a mix of economic, diplomatic, and domestic-political motivations, not easily reduced to rational choice models. 6/

global.oup.com/academic/produ…

global.oup.com/academic/produ…

In addition to these factors, developing countries suffered from a lack of expertise about what they were signing, which often led them to under-appreciate the degree of exposure to suit. This is explored in depth in work by @laugepoulsen. 7/

laugepoulsen.com/bounded-ration…

laugepoulsen.com/bounded-ration…

One of the theses of this class was that developing countries are now engaging more substantially in this system. If that is right, what has changed? 8/

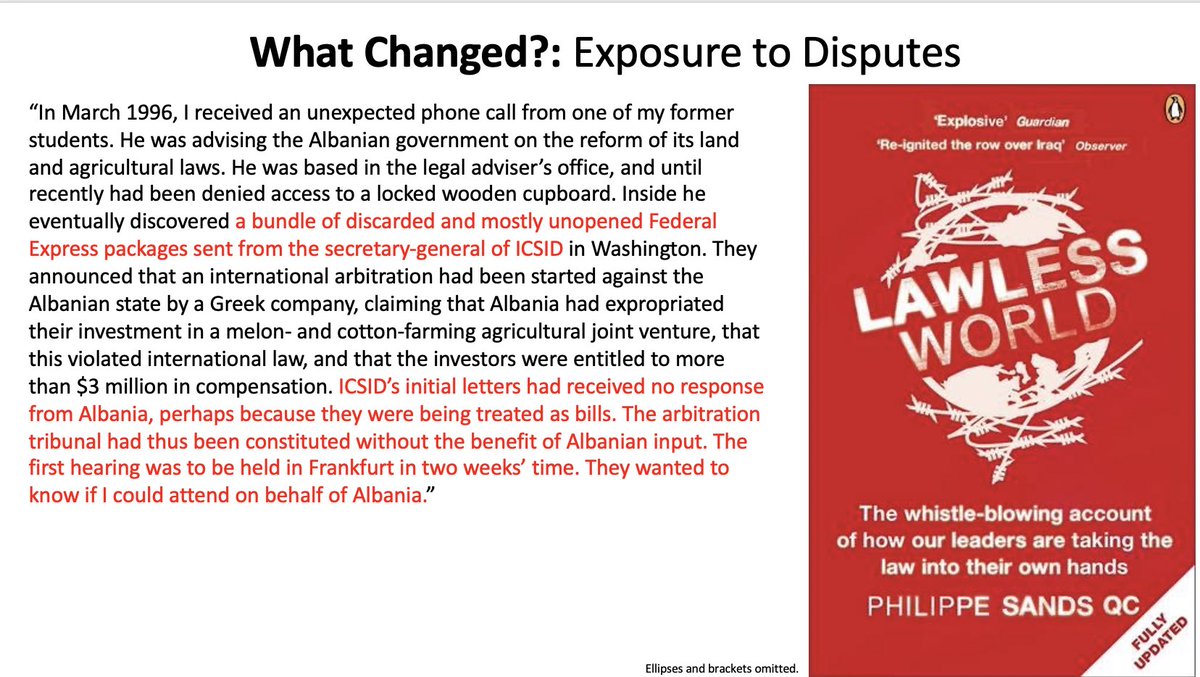

One shift is the exposure of countries to suit. @philippesands describes an early experience of Albania in the Tradex case. Once sued, states may develop relationships w/ outside counsel or build in-house expertise. 9/

(I condensed slightly the quote from Sands’ book here.)

(I condensed slightly the quote from Sands’ book here.)

Another shift is the awareness of large damages awards, as @MPaparinskis notes in his excellent “Crippling Compensation." The article opens with the juxtaposition of Venezuela’s economic collapse and the massive Conoco award. Note the dates. 10/

…library-wiley-com.libproxy.temple.edu/doi/full/10.11…

…library-wiley-com.libproxy.temple.edu/doi/full/10.11…

There is also the increasingly salient fear that BITs could operate to chill state responses to economic crises or punish states ex post for their crisis responses, as discussed in this article just published in @JIEL_OUP. 11/

https://twitter.com/jiel_oup/status/1376487297135243279

And there is the concern that ISDS obligations will conflict with public policies. The students were already familiar with Phillip Morris, so I briefly introduced them to Foresti v. South Africa instead. See here in @opiniojuris, quoting @IAReporter:

opiniojuris.org/2007/02/20/ics…

12/

opiniojuris.org/2007/02/20/ics…

12/

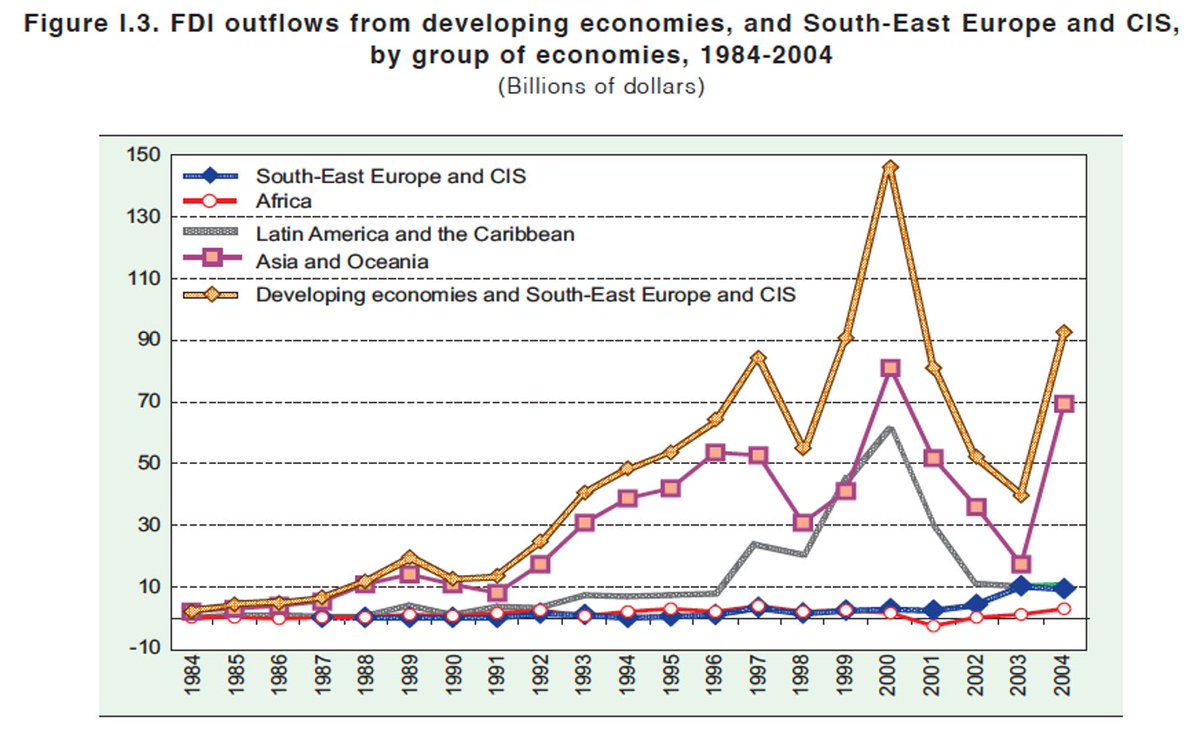

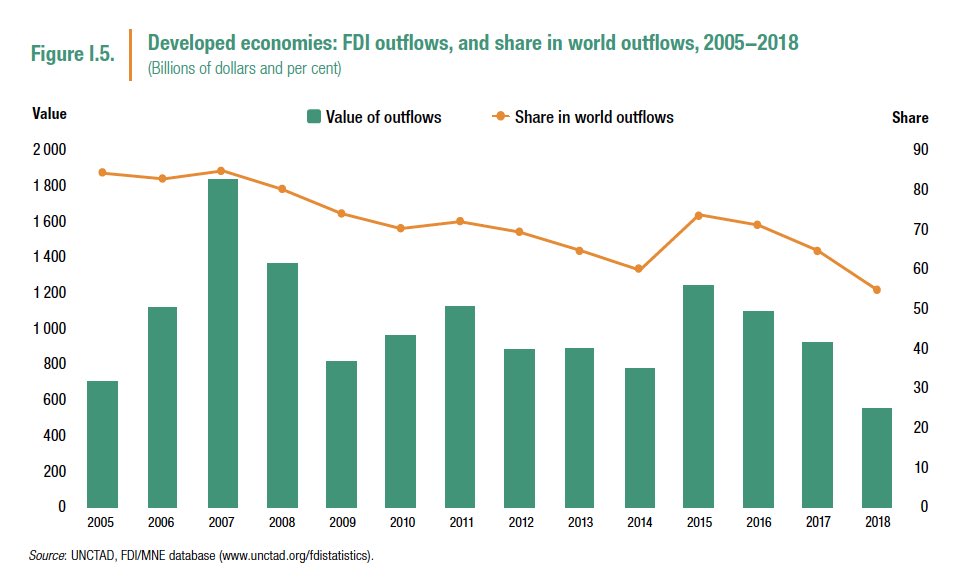

The changes are not all one-way. The 2000s saw a spike in FDI outflows from DCs, leading to a more mixed picture of who values investment protection and why. This has decreased, but it’s not the 1980s anymore. See below from @unctad 2005 and 2019 World Investment Reports:

13/

13/

So what are countries doing now? Lots of things. Countries that are newly critical of the system might seek to withdraw from existing investment treaties, as Pakistan is reportedly considering, or from institutions like ICSID. 14/

bilaterals.org/?most-of-bits-…

bilaterals.org/?most-of-bits-…

Countries might seek to renegotiate existing BITs, or seek to adopt joint interpretive statements with treaty partners, with or without a formal mechanism for doing so. India has recently attempted the latter course. 15/

iisd.org/itn/en/2016/12…

iisd.org/itn/en/2016/12…

You might stop agreeing to BITs altogether, or at least stop agreeing to investor-state dispute settlement. In addition, countries might adopt alternatives to BITs and ISDS. This is the course that South Africa adopted. 16/

news24.com/fin24/opinion/…

news24.com/fin24/opinion/…

Countries might also refocus on developing in-house expertise in the design, implementation, and litigation of investment treaties. @w_alschner & Dmitriy Skougarevskiy describe how Mauritius did this effectively while embracing the BIT system. 17/

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

You might also engage energetically in multilateral reform efforts, whether it’s the @icsid rules or UNCITRAL WG III. 18/

Finally, countries might adopt new models. The SADC Model BIT, in particular, is a template for alternative approaches to investment, and new models/treaties from India, Brazil, China, Nigeria, Colombia, and others suggest new directions. 19/

iisd.org/itn/wp-content…

iisd.org/itn/wp-content…

In class, we looked at alternative approaches that do not rely on ISDS. The first are there recent investment facilitation agreements from Brazil, which rely more on iterative dialogue, forward-looking remedies, and state-to-state dispute settlement. 20/ iisd.org/articles/compa…

The second is South Africa’s law on investment, which provides alternative standards of treatment, relies on recourse to domestic courts and mediation, and conditions access to international arbitration upon exhaustion of domestic remedies. 21/

investmentpolicy.unctad.org/investment-law…

investmentpolicy.unctad.org/investment-law…

For the second half of class, we turned away from these diplomatic questions to address the impact of investments on local communities, who, as @nicolasmperrone points out, are effectively made “invisible” by the treaty regime. 22/

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

We discussed in particular Nicolas’s work (along with @LCotula’s) on the ongoing Eco Oro v Colombia case, discussed in some detail here: iied.org/foreign-invest…

23/

23/

Finally, we discussed the impact of investment through the lens of Sawhoyamaxa Indigenous Community v. Paraguay (h/t @LawProfPuig for the reference). This case has a long history, beginning deprivation by European investors in the 19th century. 24/

corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/art…

corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/art…

This story eventually has a happy ending, but it shows how investment can have devastating consequences, and how even now BITs can be presented as a barrier to recognizing the longstanding claims of indigenous groups. /END

escr-net.org/node/365565

escr-net.org/node/365565

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh