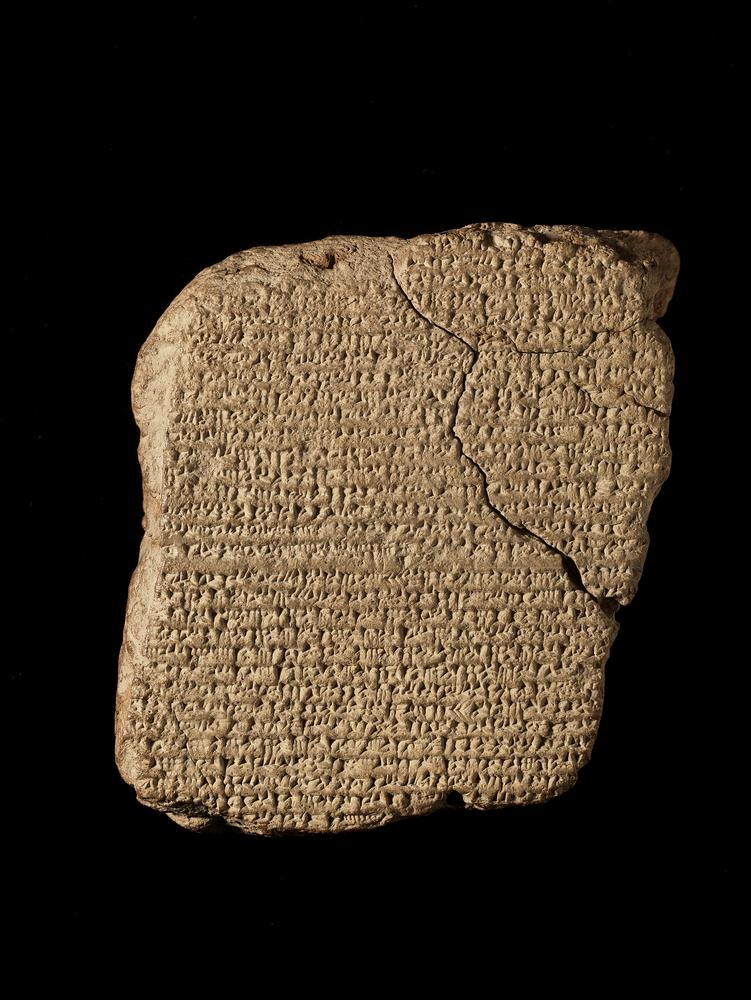

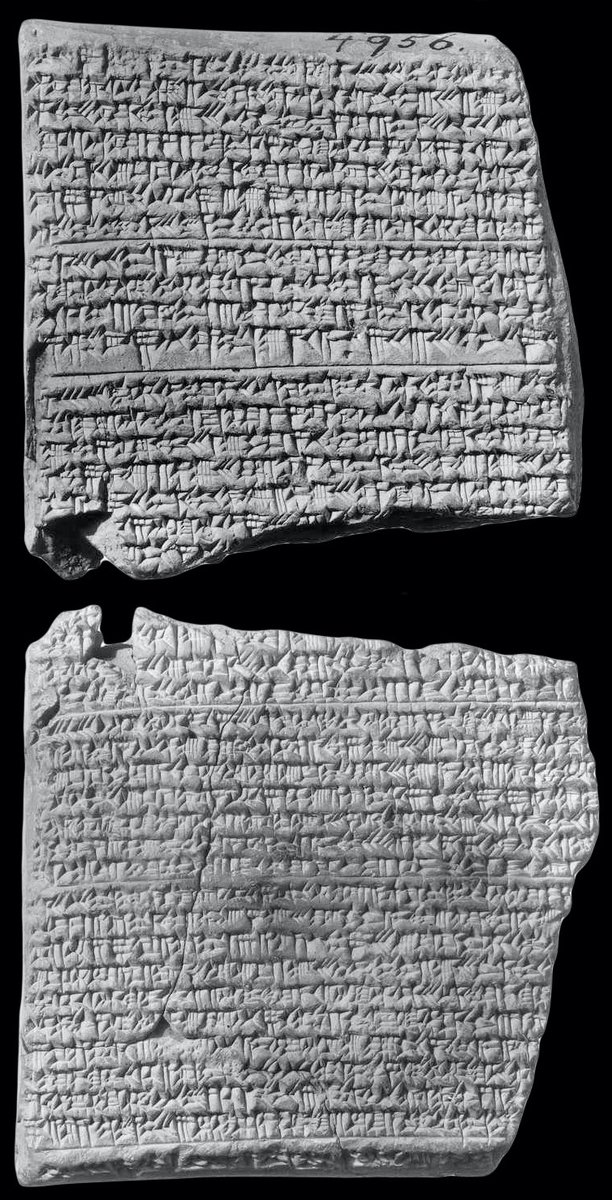

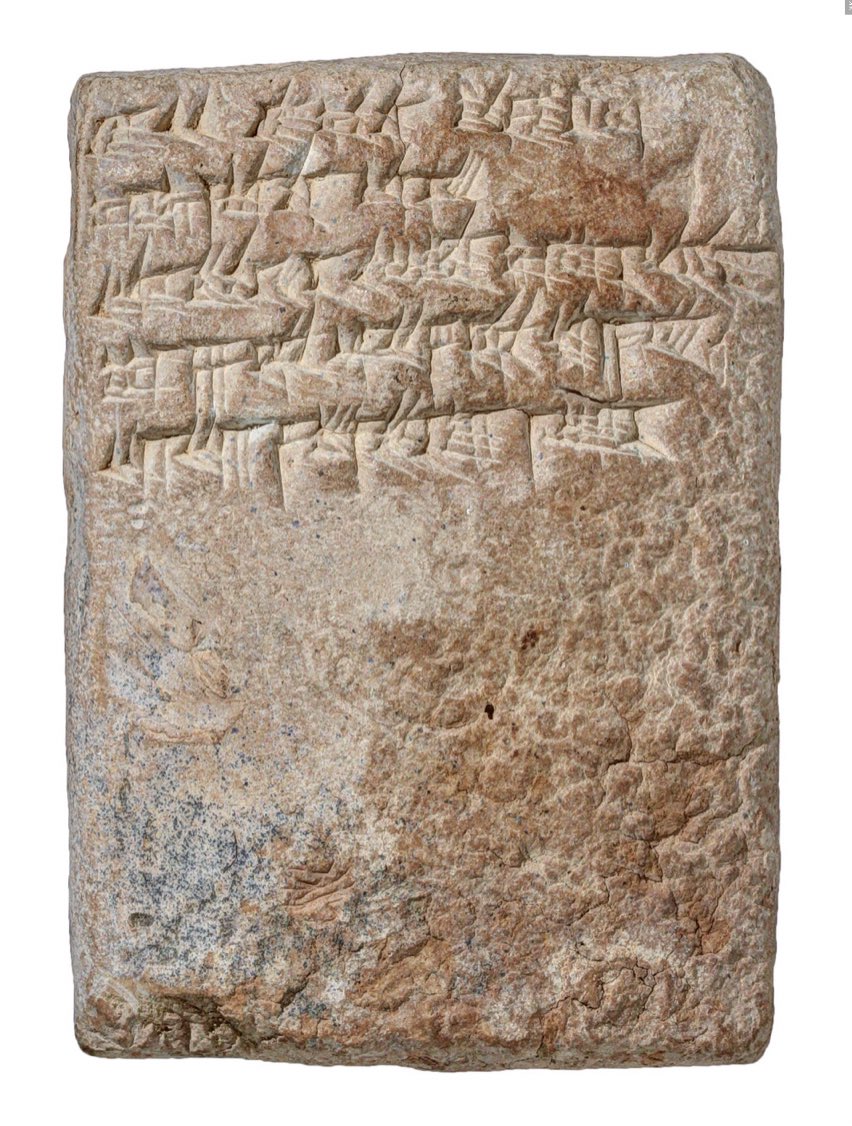

In 235 BCE, a boy named Aristocrates was born, and someone made predictions about his life based on where the sun, moon, and planets were in the sky.

“Venus was in 4° Taurus. The place of Venus (means) he will find favour wherever he goes.”

“Venus was in 4° Taurus. The place of Venus (means) he will find favour wherever he goes.”

“The moon was in 12° Aquarius. His days will be long.”

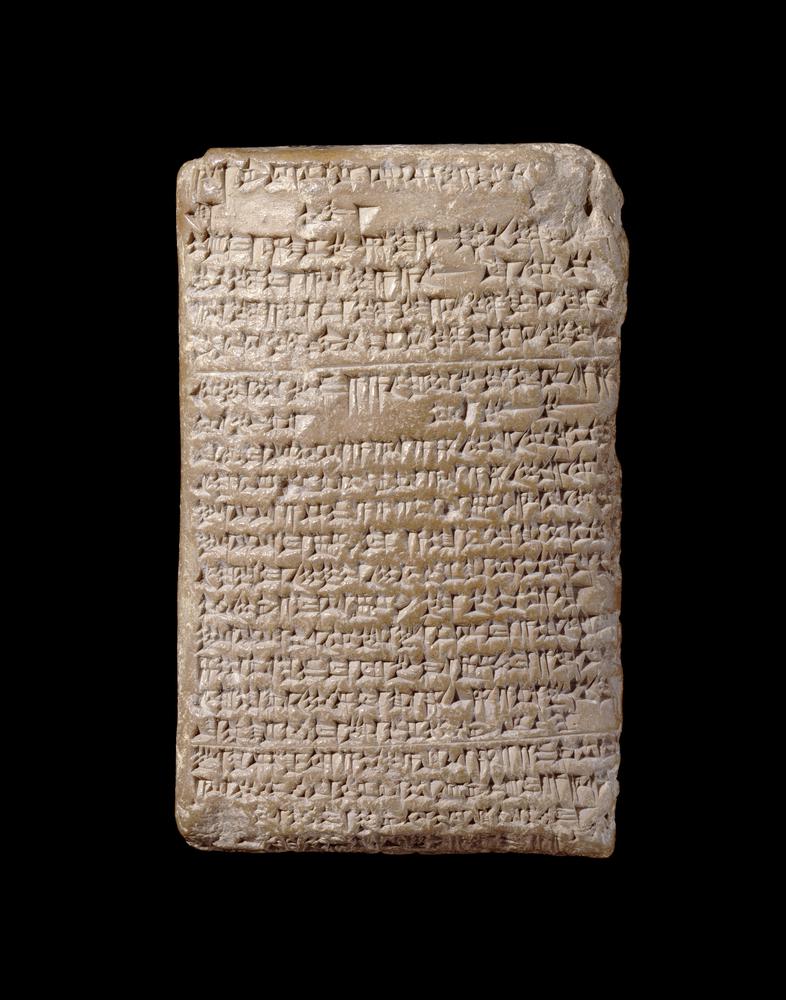

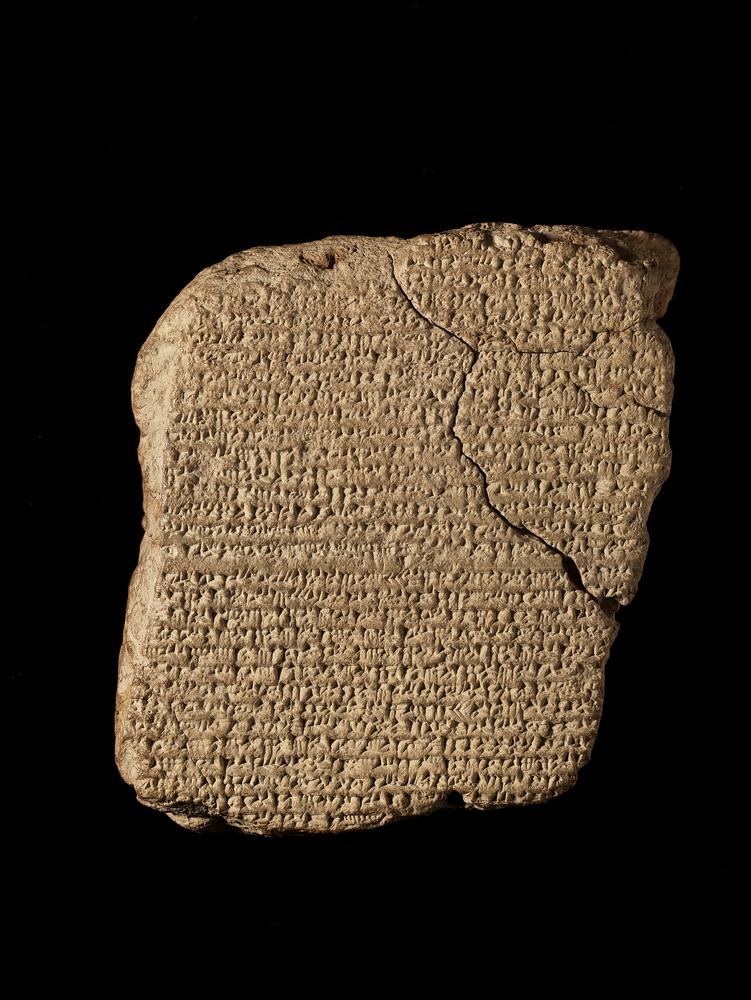

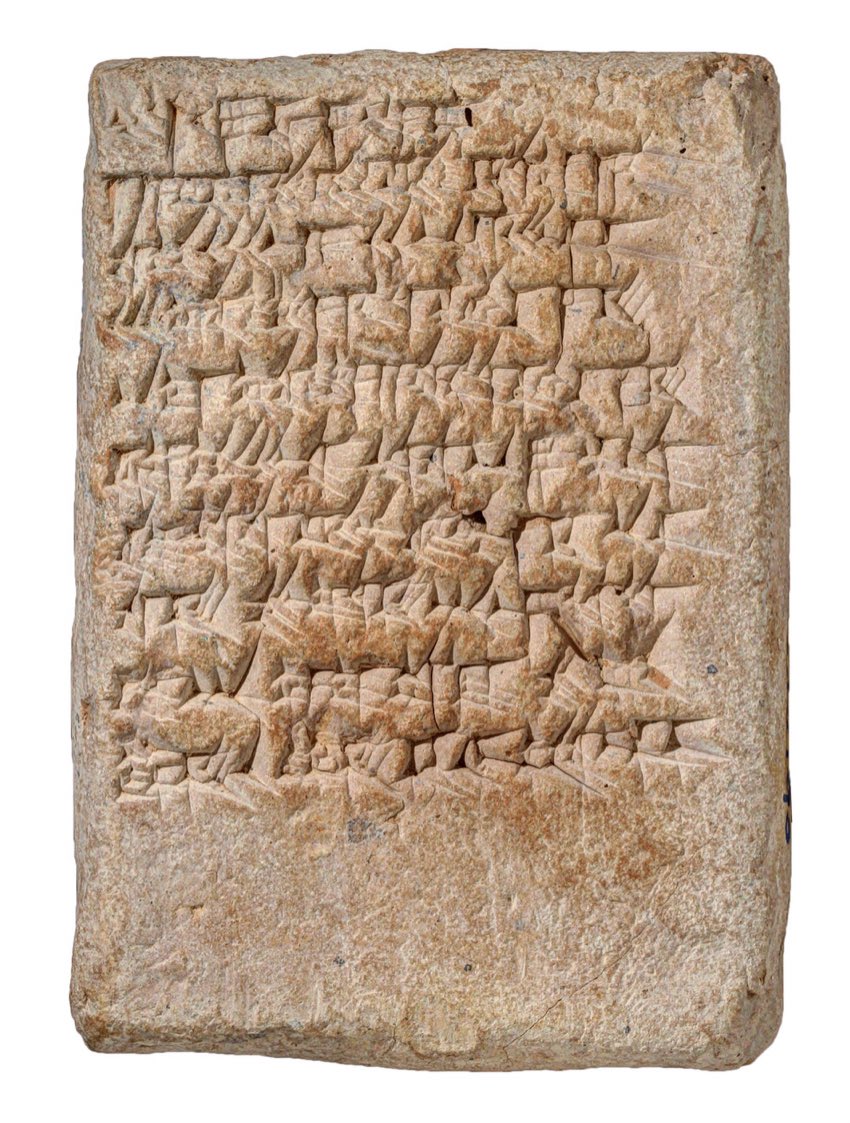

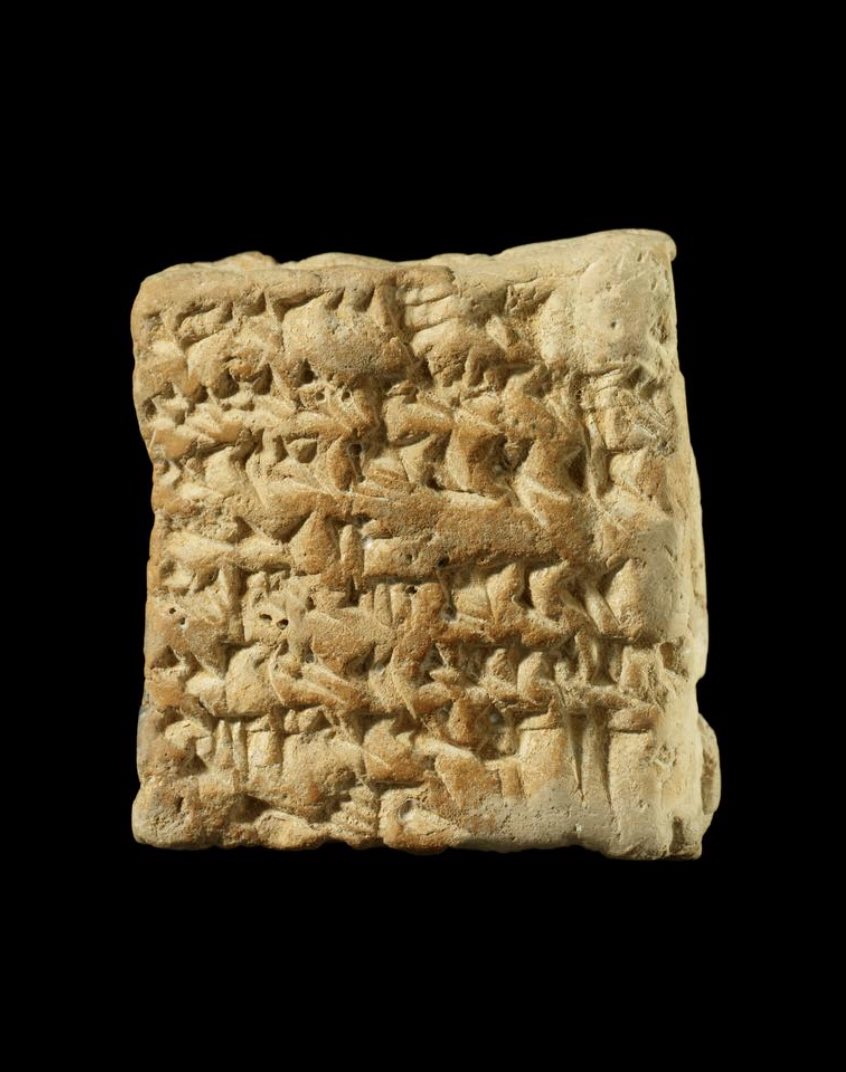

According to his horoscope, Anu-belshunu was born on December 29, 248 BCE some time in the evening, probably in Uruk. I just love that we know that about him.

According to his horoscope, Anu-belshunu was born on December 29, 248 BCE some time in the evening, probably in Uruk. I just love that we know that about him.

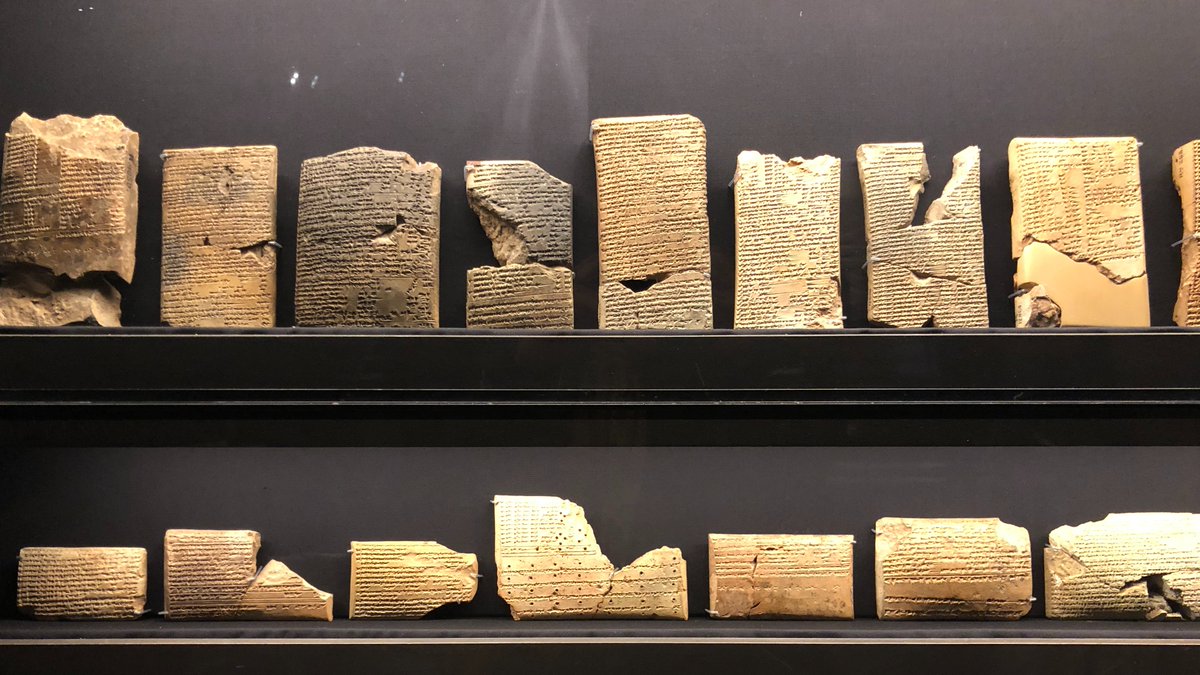

Only ~30 horoscopes survive from ancient Babylonia, and they all contain similar info in a similar order.

Date and time of birth. Positions of the sun, moon, and planets in the zodiac. Eclipses that year. Solstice and equinox data. Sometimes, a prediction.

Date and time of birth. Positions of the sun, moon, and planets in the zodiac. Eclipses that year. Solstice and equinox data. Sometimes, a prediction.

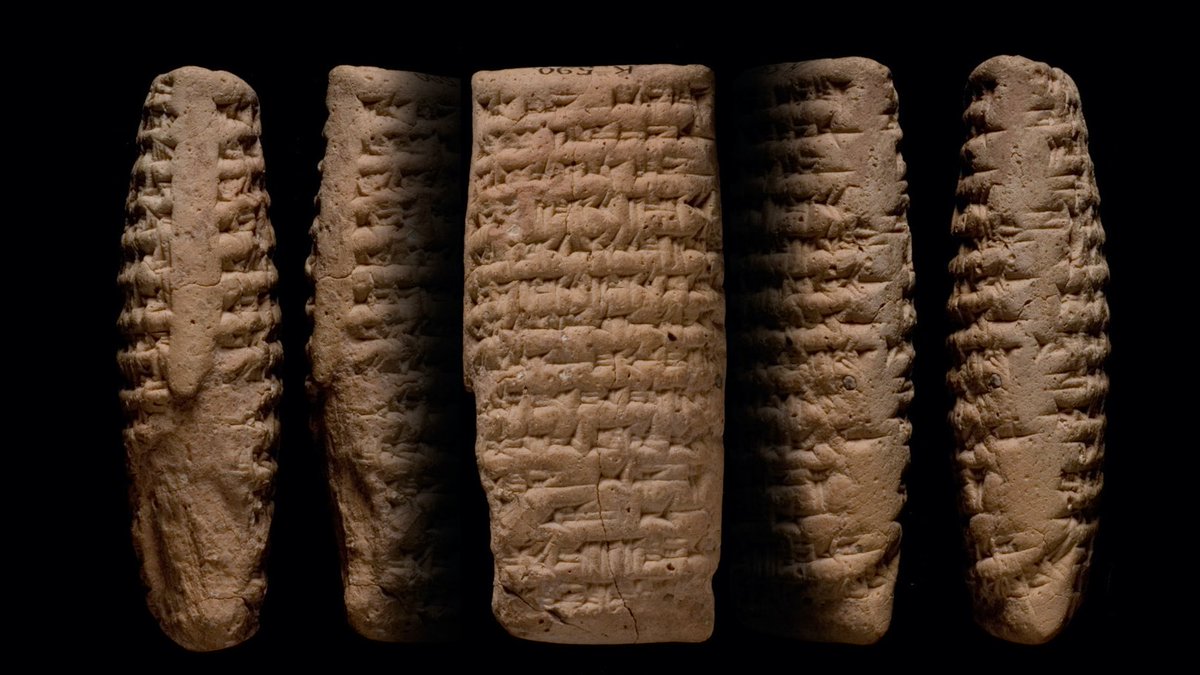

Predictions in ancient Babylonian horoscopes were not always good. On April 16, 68 BCE, a child was born whose “good fortune will diminish”.

The horoscope also records a partial lunar eclipse that took place on September 3 of that year eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/5MCLEmap/-0099…

The horoscope also records a partial lunar eclipse that took place on September 3 of that year eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/5MCLEmap/-0099…

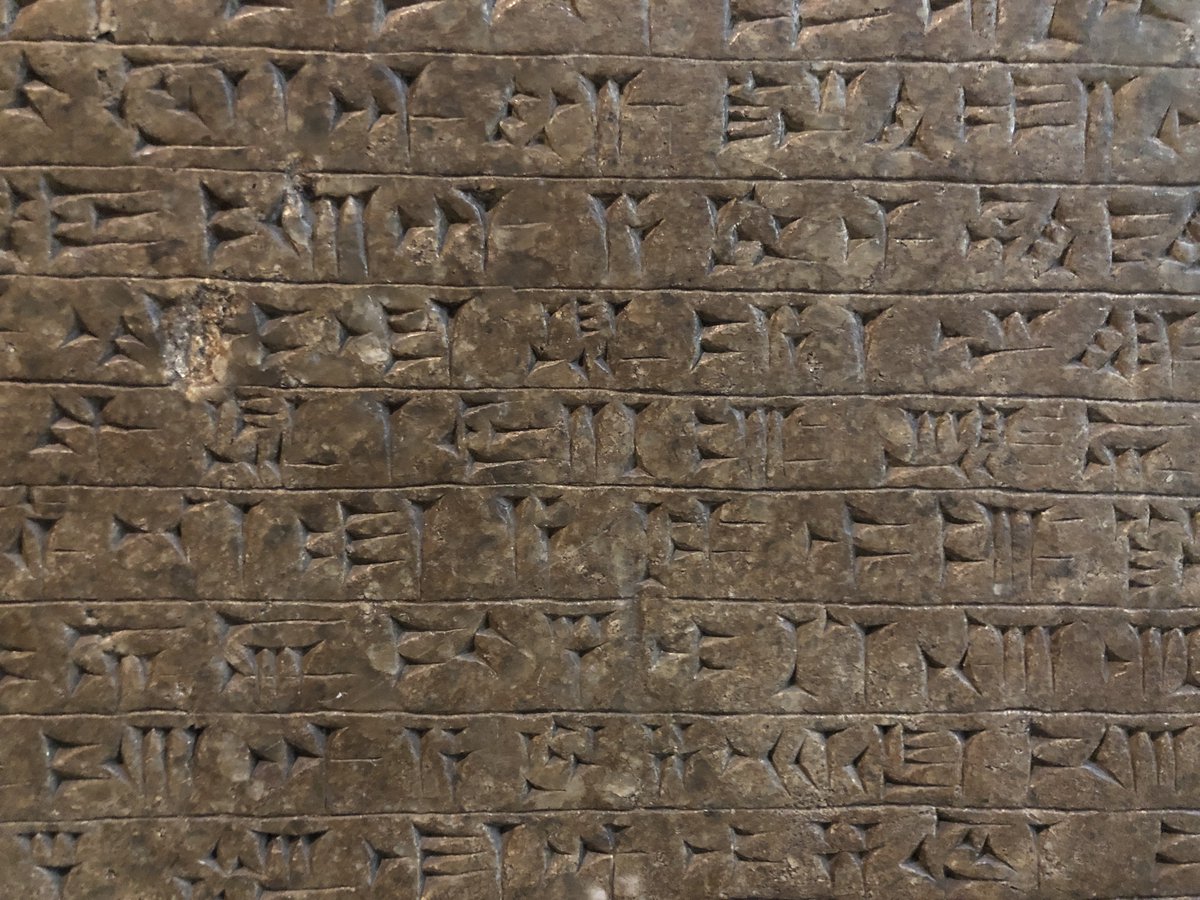

The data in Babylonian horoscopes was mined from other astronomical tablets.

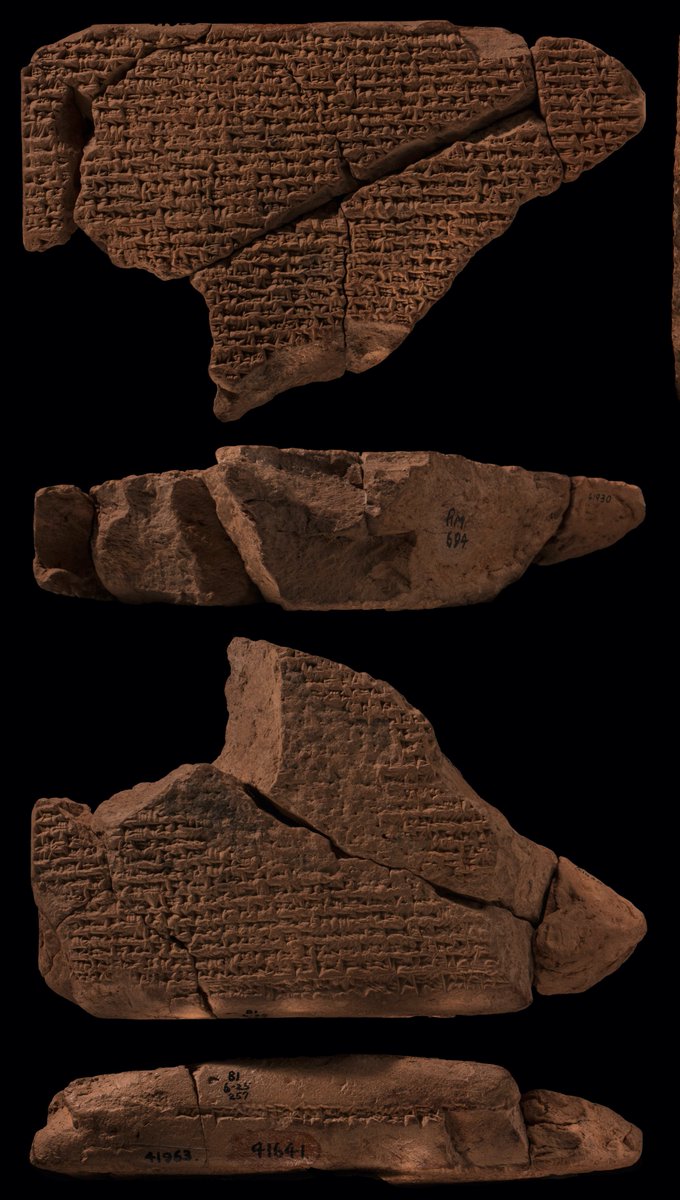

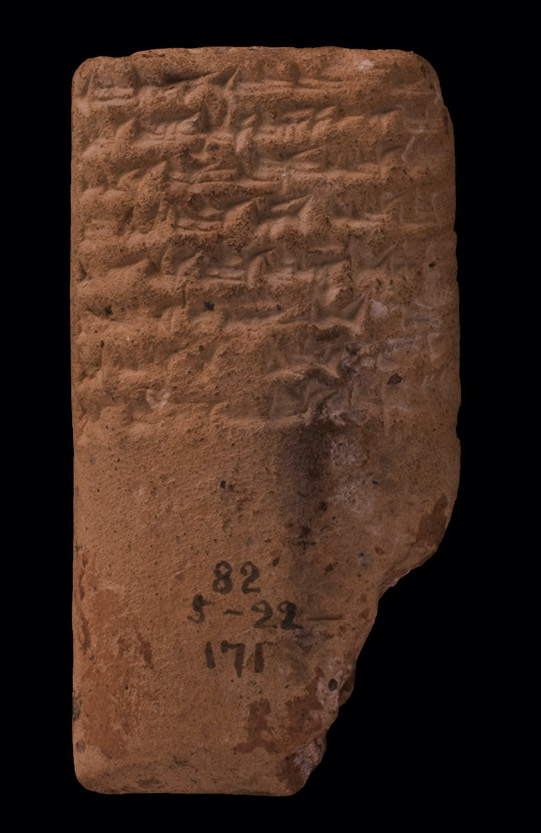

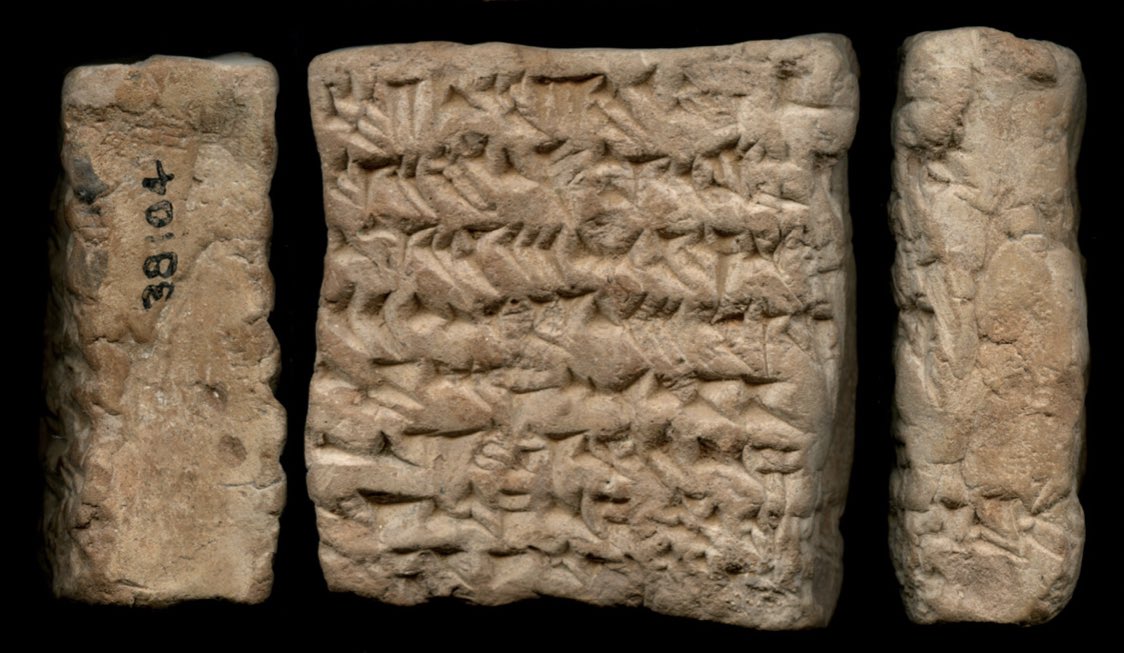

Horoscopes were written after the baby’s birthday based on that info. Birth notes that simply record a birthday have also survived, like this one for someone named Belshunu born in 292 BCE

Horoscopes were written after the baby’s birthday based on that info. Birth notes that simply record a birthday have also survived, like this one for someone named Belshunu born in 292 BCE

(Presumably, the horoscope would be put together at a later date.)

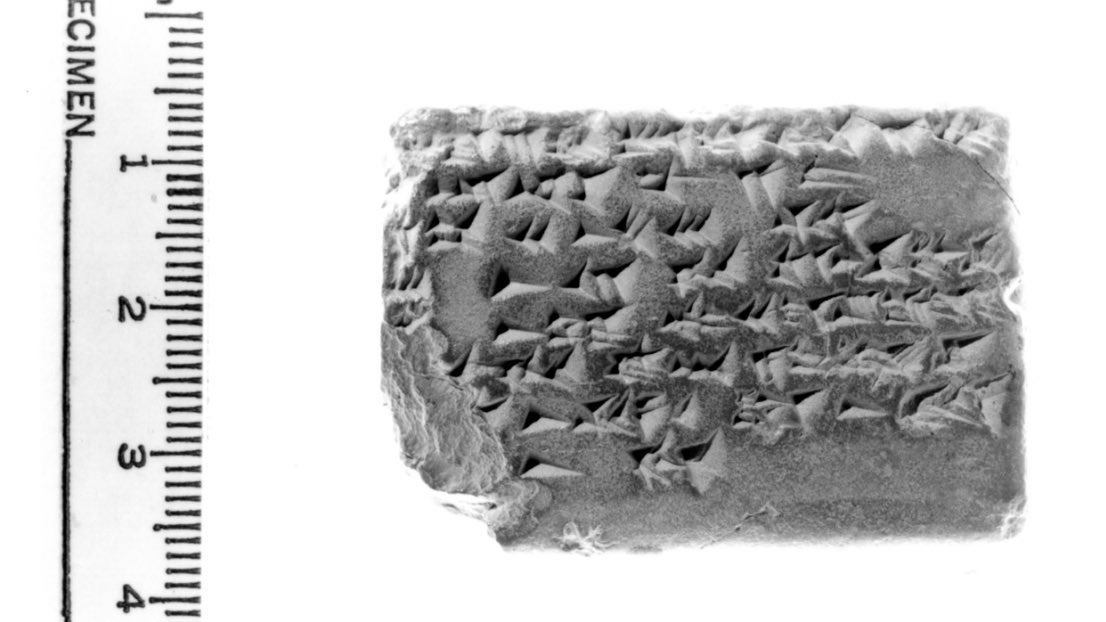

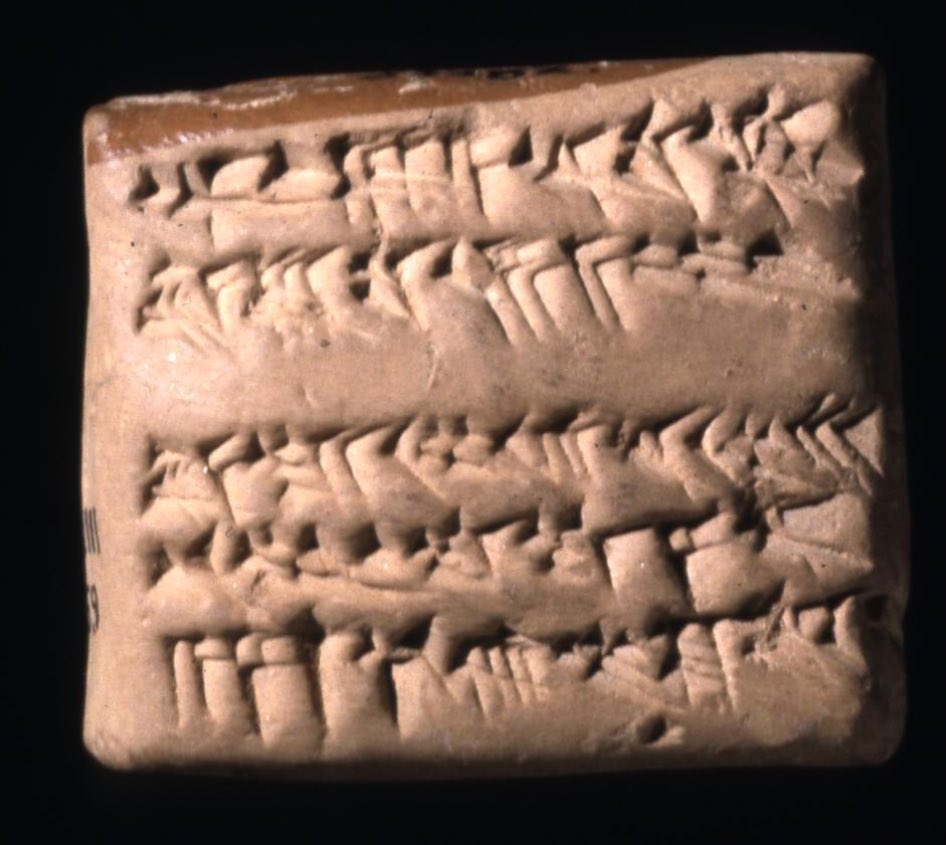

Someone named Tarsamukus (maybe?) was born on September 1, 287 BCE when Mars was in Leo, Jupiter and Venus were in Cancer, and the sun was in Virgo britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

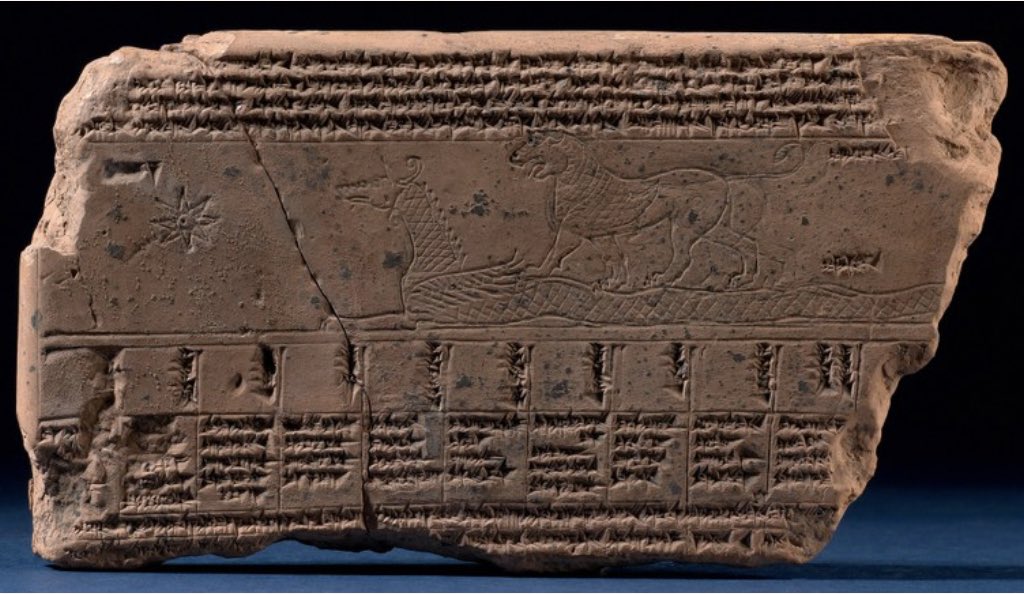

What’s cool about Babylonian horoscopes is that they show how the zodiac — developed in the mid-first millennium BCE as a way to organise astronomical observations and calculations — was extended to other stuff in people’s lives.

I mean actually what’s cool about Babylonian horoscopes is BABYLONIAN HOROSCOPES

For Aristocrates, see collections.peabody.yale.edu/search/Record/…

For Anu-Belshunu, see collections.peabody.yale.edu/search/Record/…

For Anu-Belshunu, see collections.peabody.yale.edu/search/Record/…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh