Incredible story of Iqbal Masih

Iqbal was born in 1983 in Muridke, Lahore, into a poor Christian family. Shortly after Iqbal's birth, his father, Saif Masih, abandoned the family. Iqbal's mother, Inayat, worked as a housecleaner.

Iqbal was born in 1983 in Muridke, Lahore, into a poor Christian family. Shortly after Iqbal's birth, his father, Saif Masih, abandoned the family. Iqbal's mother, Inayat, worked as a housecleaner.

In 1986, Iqbal’s family needed money to pay for a celebration. For a very poor family in Pakistan, the only way to borrow money is to ask a local employer. Iqbal's family borrowed 600 rupees from a man who owned a carpet-weaving business.

In return, Iqbal was put under the system of peshgi (loans) which is inherently inequitable; where the employer has all the power. At age four, Iqbal was sold by his family to pay off their debts.

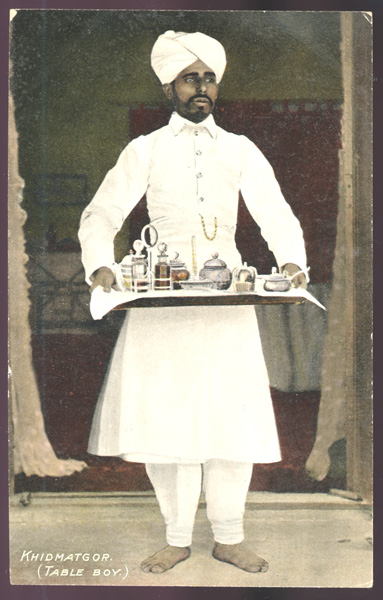

Iqbal worked six days a week, at least 14 hours a day. The room in which he worked was stifling hot because the windows could not be opened in order to protect the quality of the wool. Only two light bulbs dangled above the young children.

If the children talked back, ran away, were homesick, or were physically sick, they were punished. Punishment included severe beatings, being chained to their loom, extended periods of isolation in a dark closet, and being hung upside down.

At the age of 10, Iqbal escaped his slavery, after learning that bonded labor was declared illegal by the Supreme Court of Pakistan (1992). In addition, all such outstanding loans were canceled by the government of Pakistan.

He escaped and went to the police to report, but the police brought him back to the factory. Iqbal’s punishment for escaping was extreme starvation and horrific beating sessions and time halted for the brave young boy as the suffering seemed unending.

Iqbal escaped a second time and went on to attend the Bonded Labour Liberation Front (BLLF) School. At the school, Iqbal spoke about his own experiences as a bonded child laborer. He spoke with such conviction that many took notice of him.

Iqbal's six years as a bonded child had affected him physically as well as mentally. At age ten, he was less than four feet tall and weighed a mere 60 pounds. His body had stopped growing, which one doctor described as "psychological dwarfism."

But this didn't stop Iqbal. He helped over 3,000 Pakistani children that were in bonded labor to escape to freedom and made speeches about child labor throughout the world. He expressed a desire to become a lawyer to better equip him to free bonded laborers.

Iqbal was fatally shot by the carpet Mafia, while visiting relatives in Muridke, Pakistan on 16 April 1995, Easter Sunday. He was 12 years old at the time.

Millions of children still work in factories in similar horrific conditions as Iqbal experienced.

Millions of children still work in factories in similar horrific conditions as Iqbal experienced.

In 2014 Nobel Peace Prize winner Kailash Satyarth dedicated his award to Iqbal Masih.

A short documentary on Iqbal Masih

A short documentary on Iqbal Masih

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh