In the 1950s, nuclear was the energy of the future. Two generations later, it provides only about 10% of world electricity, and reactor design hasn‘t fundamentally changed in decades. Why has it been a flop? Here's my review of a recent book on that topic: rootsofprogress.org/devanney-on-th…

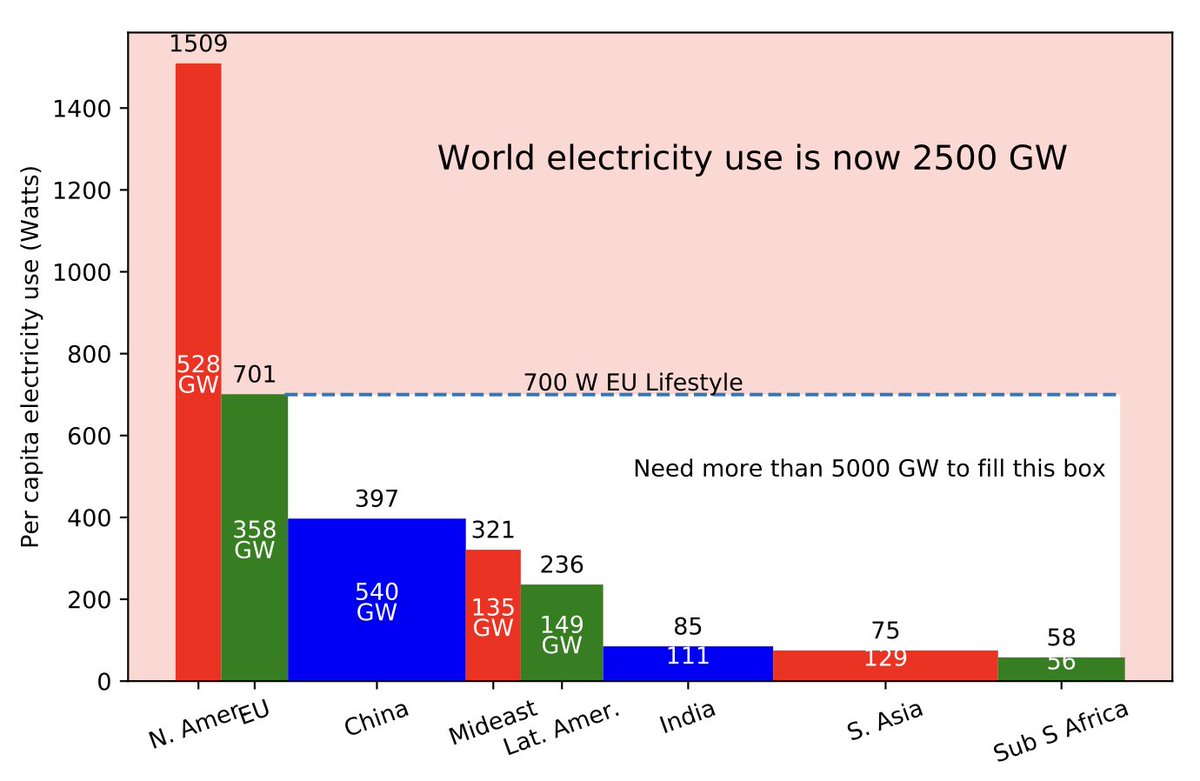

Nuclear power is the sword that can cut the Gordian knot of providing cheap energy to the world while reducing CO2 emissions. And we're going to need a lot more energy: 5TW to give today's world the energy standard of Europe; 25TW to support 12B people in a decarbonized economy.

But nuclear is more expensive than gas (7–8c/kWh) or coal (5c/kWh), mainly because of plant construction costs. These costs were dropping in the US until 1970—then started soaring. In contrast, Korea can still build for $2.50/W, which prices nuclear electricity < 4c/kWh.

The standard story about nuclear costs is that radiation is dangerous, and therefore safety is expensive. The book argues that this is wrong: nuclear can be made safe and cheap.

One problem is that policy is guided by the Linear No Threshold theory of radiation damage (LNT), which says: cancer risk is proportional to dose, doses are cumulative over time regardless of rate, and there is no threshold / safe dose.

This contradicts both evidence and theory.

This contradicts both evidence and theory.

Cells have repair mechanisms to fix broken DNA, which gets broken all the time (not just from radiation). However, the mechanism is highly non-linear: as the break rate increases, the error rate of the repair process goes up drastically.

The book assembles evidence about radiation damage from a range of studies: nuclear bomb survivors, radon gas, animal experiments, high–background radiation areas, and occupational exposure, including the Chernobyl cleanup crew and the women who painted radium onto watch dials.

There was even a 1950 trial that violated every standard of medical ethics by *injecting unknowing and non-consenting patients with plutonium*.

All of the patients had been diagnosed with terminal disease. None of them died from the plutonium…

All of the patients had been diagnosed with terminal disease. None of them died from the plutonium…

… including one patient, Albert Stevens, who had been *misdiagnosed* with terminal stomach cancer that turned out to be an operable ulcer. He lived for more than twenty years after the experiment, and died from heart failure at the age of 79.

Excessive concern about radiation led to a regulatory standard known as ALARA: As Low As Reasonably Achievable. What defines “reasonable”? As long as the costs of nuclear plant construction and operation are in the ballpark of other modes of power, then they are reasonable.

This eliminates, by definition, any chance for nuclear to be cheaper than its competition. Nuclear can‘t even innovate its way out of this predicament: under ALARA, anything that reduces costs simply allows—indeed, requires—the regulator to push for more strict requirements.

In one case, a spent fuel cask from a storage pool dribbled some water on the blacktop. The entire path of the forklift was dug up, creating a trench 2' wide by 0.5 miles long.

It was repaved with material naturally high in thorium that was more radioactive than what was dug up.

It was repaved with material naturally high in thorium that was more radioactive than what was dug up.

The people at NRC are not anti-nuclear, but they are captive to institutional logic and incentives. They don't have a mandate to increase nuclear power. They get no credit for approving new plants. But they do own any problems. For the regulator, there‘s no upside, only downside.

Further, the nuclear companies pay the NRC for time spent reviewing applications, creating a perverse incentive: the more overhead, the more delays, the more revenue for the agency.

Result: the NRC process takes several years and costs literally hundreds of millions of dollars.

Result: the NRC process takes several years and costs literally hundreds of millions of dollars.

Devanney blames not just the regulators, but the whole nuclear complex for foisting upon the public a huge lie: that radiation release in a nuclear accident is virtually impossible and will never happen, or with a frequency of less than one in a million reactor-years.

Instead, the industry should communicate the truth: releases are rare, but they will happen; and they are bad, but not unthinkably bad. There were zero deaths from radiation at Three Mile Island or at Fukushima.

Other themes in the book: the substitution of probabilistic models and formal QA procedures for rigorous testing; the lack of competition in an industry that has grown fat at the public trough.

Devanney proposes practical alternatives for everything he criticizes: For instance, replace ALARA with specific limits set in the context of nuclear's alternatives. Fund the NRC via an electricity tax rather than review fees, to align incentives.

At the end of the day, Devanney is not optimistic that deep reform will happen any wealthy country. The best prospect for nuclear is a poor country with a strong need for cheap, clean power. (His company, @ThorconPower, is building its thorium-fueled reactor in Indonesia.)

I don‘t yet know enough to fully evaluate the book, but I found it compelling. It pulls together academic research, industry anecdotes, and personal experience into a cogent narrative that pulls no punches. Well worth reading.

Read my full review and get the book here (free PDF download or paperback on Amazon):

https://twitter.com/rootsofprogress/status/1383094803433357315

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh