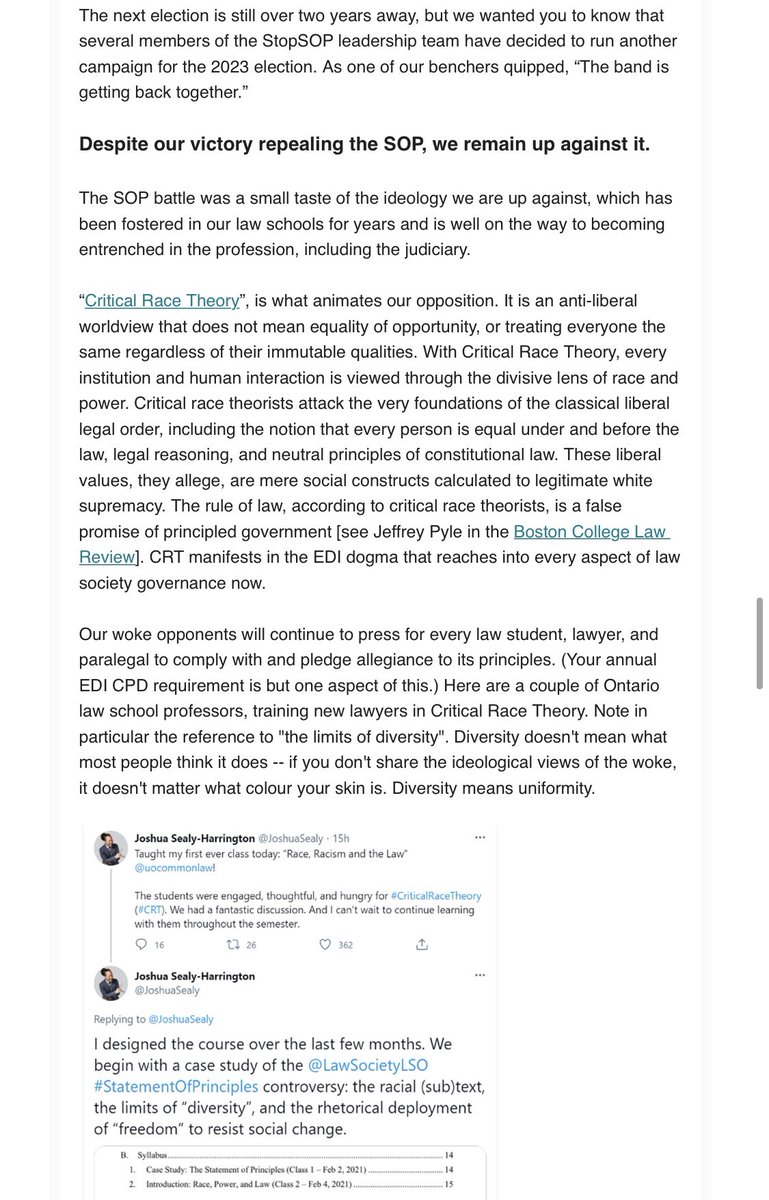

After the final “Race, Racism and the Law” class @uocommonlaw, my incredible students compiled a video of appreciation for what the course meant to them in their legal studies.

I was incredibly touched (😭). And listening to their reflections caused me to reflect on #LegalEd 🧵

I was incredibly touched (😭). And listening to their reflections caused me to reflect on #LegalEd 🧵

The students’ comments reflected consistent themes:

-rethinking the type of legal career they want to pursue;

-having space for candid conversations where they can be authentic;

-craving critical perspectives and gentle challenge; &

-feeling empowered by critical racial literacy

-rethinking the type of legal career they want to pursue;

-having space for candid conversations where they can be authentic;

-craving critical perspectives and gentle challenge; &

-feeling empowered by critical racial literacy

In this current moment—where the Ontario government not only neglected racialized and low-income communities in the midst of a global pandemic, but now, is turning to measures that will needlessly punish those same communities—these student comments take on acute significance.

And these comments match those I’ve received from many students across Canada who have reached out following workshops or guest lectures throughout the year on #CriticalRaceTheory.

I believe that many students crave greater access to critical perspectives on law—especially now.

I believe that many students crave greater access to critical perspectives on law—especially now.

Of course, what students want isn’t the sole metric for how legal education should be designed. Indeed, I think students who don’t want to learn about critical perspectives still should. But there is, I can see, latent untapped interest in critical theory from many students.

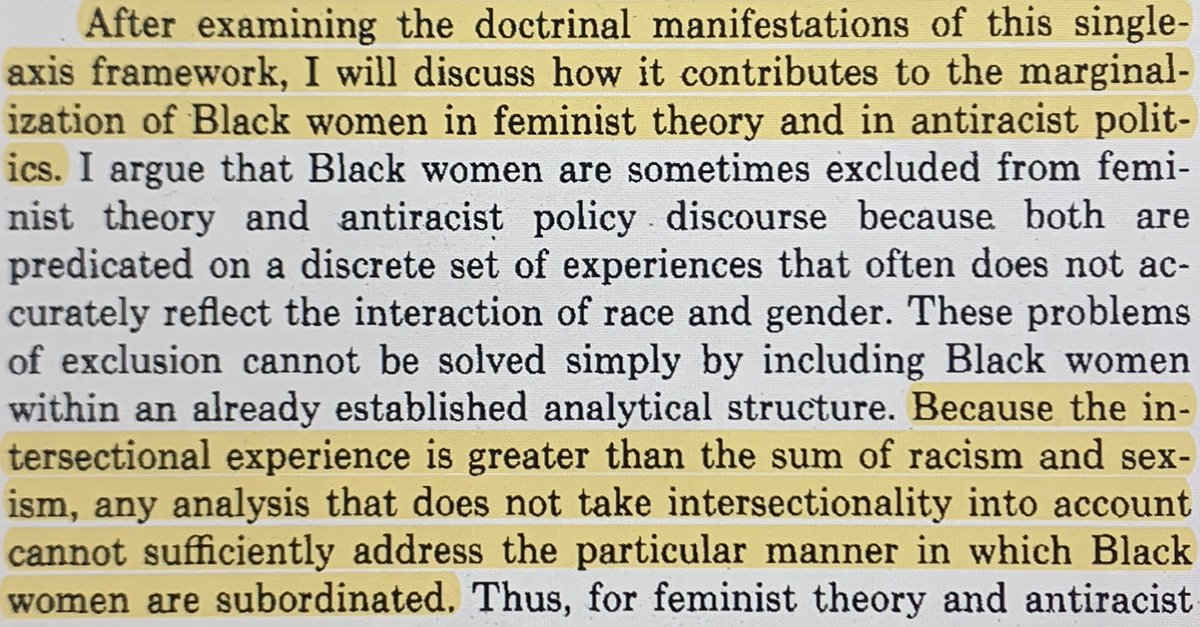

The discussion of critical theory in law often gets misrepresented as whether legal education should or should not be ideological. This is a false dilemma. However one teaches the law implicates ideology. The real question, thus, is *how* law schools interact with ideology.

Teaching property without reference to slavery *is* ideological.

Teaching crime without reference to white supremacy *is* ideological.

Teaching torts without reference to capitalism *is* ideological.

You’re either framing power in your analysis, or obscuring it.

Teaching crime without reference to white supremacy *is* ideological.

Teaching torts without reference to capitalism *is* ideological.

You’re either framing power in your analysis, or obscuring it.

Further, even on the narrowest conception of legal ed, this context is crucial. Veteran lawyers know that storytelling matters, and that judicial ideology is fundamental to effective legal advocacy. Thus, to overlook ideology is not simply a moral omission, but a legal one.

For these reasons, the idea that critical theory undermines doctrinal analysis is flawed. Law’s myriad, but necessary, abstractions—from “reasonableness” to “proportionality”—do ideological work. To not teach ideology, then, is to not teach significant portions of “the law”.

And so, while I was thrilled to provide students with space to have difficult conversations on race and the law, my intent was not only political, but doctrinal. Those students now have a vocabulary to discuss race and law, but they also have a sensitivity to power and reasoning.

Ontario’s new racist Covid restrictions, endless police murders of Black people, vaccine apartheid... These are not simply *legal* issues; they are *racial* issues that lawyers should be equipped to understand and respond to—a point I emphasized each class with #ThisWeekInPower.

To some, the Covid pandemic & recent uprisings have generated new perspectives on racial hierarchy in Canada. I would implore lawyers to go even further, and recognize the ways in which legal mechanisms are specifically complicit in the creation and maintenance of that hierarchy.

The focus of my scholarship & advocacy only goes so far. So, while I strove to teach widely, I am indebted to the many brilliant guest speakers—activists, lawyers, judges—who graced my course with their brilliance, & whose visits the students specifically mentioned as invaluable.

Thank you Patricia Williams, @debthompsonphd, @KimTallBear, @dtanovich, @amarkhoday, Harry LaForme, Dean Young, @Pam_Palmater, @avnishnanda, @Reakash, @JWatsonHamilton, @Ido_Katri, Justice Abella, @ummni, & @HarshaWalia. This course did not have a single Professor, but many.

Lastly, thank you to my students. Watching your end of class video was one of the most touching moments in my life. And your endless enthusiasm, curiosity, and rigour throughout the course was an absolute joy to engage with. This first class will always be deeply special to me.

Unlike the infinitely generous @SarahMasonCase, I won’t post my full syllabus here (because I lack her concision, and mine is obnoxiously long—sorry students!)

But the topics are outlined below, and I am happy to discuss the course and share the syllabus with others.

But the topics are outlined below, and I am happy to discuss the course and share the syllabus with others.

I’m also keen to discuss with other #CriticalRaceTheory scholars about how they approach their own courses. I’m certain my approach will evolve overtime. And I think the project of infusing the legal academy with a greater orientation towards racial justice is a collective one.

As we continue to critique governments across North America for their reification of white supremacy, please remember: this is not new, it is simply, to some, now more transparent. Law should not be our only or even primary site of struggle, but it is, I believe, a crucial one.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh