Though the Odyssey has long been favored in high school curricula, Homer’s Iliad has had a massive resurgence in Internet culture, becoming the preferred topic of fan fiction, art, and memes.

This is in no small part due to Madeline Miller’s “Song of Achilles” (2011) which painted the pair in a romance so delicious, Tumblr and social media at large couldn’t help but salivate.

But an essential (and distinct) part of #Patrochilles content lies outside the romance it draws between these figures. Almost as important is how it views the deniers of their relationship––the villains to our heroes.

Just as these memes serve to validate the couple, so too do they act as polemics against detractors. Hence why many simply mock Troy (2004), an apotheosis of “no homo” culture which doubles as poor film.

Still, a more frequent target of fans’ ire is not found in pop culture, but academia: the professors who downplay the pair in scholarship. So common is this sentiment, it is strange to see a meme that lacks it. Without some quip about “historians” or “classicists.”

Now, don’t get me wrong: this is hilarious. One of the main things that sold me on #ClassicsTwitter was the way it dunks on the academy. After long hours dealing with scholastic pedantry, nothing is more refreshing.

But with its prominence online, “historian” discourse has started giving a bad impression. Not that scholars are pedants or sticklers, but bigots and homophobes. Like any field, classics may suffer from its biases. Still, we should remember how Twitter can exaggerate.

So, in the interest of getting to the bottom of this, I wanted to talk #Patrochilles and its reception. Not just in memes today, but through its long and storied history:

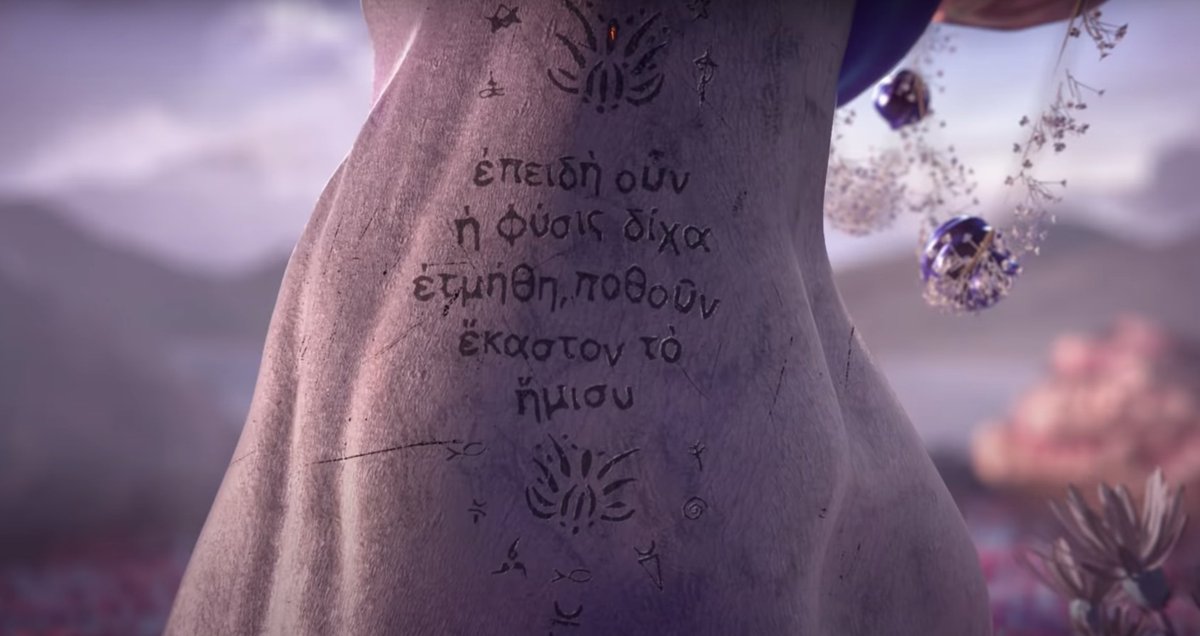

By the 4th century, Plato not only states the two are involved (Symp. 179e-180a) but argues with Aeschylus (Myrm. fr. 135-136) over who the ἐραστής is––that is, who topped. This pederastic relationship may not be “gay” or “queer” exactly, but at least we know they fucked, right?

Well, though the philosopher and playwright were soundly team #Patrochilles, their word is not final. Coming centuries after Homer, they are liable, like us, to project. So rather than their commentary, we look to the source of it. What does the Iliad say of this romance?

Several passages come to mind. Achilles tells Patroclus he wishes “not one of all the Trojans could escape destruction, not one of the Argives, but you and I could emerge from the slaughter so that we two alone could break Troy’s hallowed coronal.” (16.98-100, trans. Lattimore)

This urge to be secluded together is echoed when Patroclus dies, and his ghost tells Achilles to “let one single vessel...hold both our ashes” (23.91-2). Living or dead, the two are inseparable.

And then, of course, there’s how Achilles first reacts to news of Patroclus’ death:

“...the black cloud of sorrow closed on Achilleus. In both hands he caught up the grimy dust, and poured it over his head and face, and fouled his handsome countenance…”

“...the black cloud of sorrow closed on Achilleus. In both hands he caught up the grimy dust, and poured it over his head and face, and fouled his handsome countenance…”

When the handmaidens come, he continues mourning, leading as “all of them beat their breasts with their hands, and the limbs went slack in each of them.” (18.22-4; 30-1)

His strength in this scene is not completely downplayed; the messenger, Antilochus, fears Achilles may turn to kill him any moment for the news (18.32-4). But our hero’s grief is spectacular in its vulnerability––in the manner that it is distinctly feminine.

Achilles, scourge of cities, best of Achaeans, bane of Troy. This is who we see, distraught and unraveled. For so great a man to fall like this, the loss must be immeasurable. This scene is a testament to his feelings for Patroclus––to the strength of their relationship.

But "strong" does not categorize their bond. Is it romantic? Sexual? Alone, these passages cannot say. Sure, there is an appeal to subtlety; love is often best left unsaid. Yet, as Fantuzzi argues in his book on the topic, Homer is not one to imply what he means.

And the bard doesn't simply wink and nudge the whole time. Consider when the pair sleeps together:

"But Achilleus slept in the inward corner of the strong-built shelter, and a woman lay beside him, one he had taken from Lesbos, Phorbas' daughter, Diomede of the fair colouring.

"But Achilleus slept in the inward corner of the strong-built shelter, and a woman lay beside him, one he had taken from Lesbos, Phorbas' daughter, Diomede of the fair colouring.

...In the other corner Patroklos went to bed; with him also was a girl, Iphis the fair-girdled, whom brilliant Achilleus gave him, when he took sheer Skyros, Enyeus' citadel." (9.663-9)

The poet has no need to include this. Achilles' visitors are leaving his camp, allowing the scene to fade and us to wonder. Yet not only does Homer place the two apart from each other, he gives each a slave-girl for company. Why do this if he saw them as lovers?

In academia, this conflicting evidence has caused centuries of debate. Fantuzzi and those that reject their love may comprise the majority today, but after three millennia, the argument is unlikely to truly settle.

Yet as the Internet looks on, it often sees a monolith of opinion. One rooted not so much in curiosity or interest, as much as the desire to judge.

On the one hand, I hope fans learn to be more charitable with scholars. To understand that they are making descriptive claims about these texts, not moral statements on right and wrong.

On the other, I think we scholars must be understanding as well, and see how for many this isn’t some argument about archaic texts, but love and its place in the world.

As long as students do not feel comfortable in classrooms, our scholarly qualms will be read as personal attacks. We cannot change the realities of Homer, but we can and must transform the culture of our study today.

So why don’t we come towards these fans and students? Celebrate their work succeeding Plato and Aeschylus? After all, not only do Patroclus and Achilles show a bright new future for ancient material––they look pretty damn cute together, too.

For those that made it to the end, I offer one final hot take: top and bottom discourse blinds us to an even greater third possibility, swift-footed “vers” Achilles.

-β

-β

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh