New preprint 🎉

Oxytocin receptor (OXTR) expression patterns in the brain across development osf.io/j3b5d/

Here we identify OXTR gene expression patterns across the lifespan along with gene-gene co-expression patterns and potential health implications

[THREAD]

Oxytocin receptor (OXTR) expression patterns in the brain across development osf.io/j3b5d/

Here we identify OXTR gene expression patterns across the lifespan along with gene-gene co-expression patterns and potential health implications

[THREAD]

So, let's begin with some background.

As well as being an oxytocin researcher I'm also a meta-scientist, which means that a lot of my work on improving research methods is focused on improving oxytocin research (that's what got me into meta-science in the first place)

As well as being an oxytocin researcher I'm also a meta-scientist, which means that a lot of my work on improving research methods is focused on improving oxytocin research (that's what got me into meta-science in the first place)

Earlier this year, we published a paper, led by @fuyu00, in which we proposed that three things are required to improving the precision of intranasal oxytocin research: Improved methods, reproducibility, and theory.

Read the article here: rdcu.be/cjeok

Read the article here: rdcu.be/cjeok

The psych sciences have made a good start on improving methods and reproducibility, but they're lagging a bit when it comes to theory.

It doesn't matter if you have good methods or reproducibility if you're asking the wrong questions in the first place rdcu.be/cjeqf

It doesn't matter if you have good methods or reproducibility if you're asking the wrong questions in the first place rdcu.be/cjeqf

To address this theory gap, we recently proposed the allostatic theory of oxytocin: that oxytocin helps maintain stability in changing environments

Open access: doi.org/10.1016/j.tics…

Open access: doi.org/10.1016/j.tics…

We used Tinbergen's "four questions" as a scaffold to develop this theory: how does oxytocin work; how does the role of oxytocin change during development; how does oxytocin enhance survival; and how did the oxytocin system evolve?

The theory was informed by lots of data on how the oxytocin system works and how it may enhance survival, but there's less data on how its role changes across development or how it evolved.

That's where this study comes in...

That's where this study comes in...

In a 2019 paper we reported oxytocin receptor expression patterns in the adult brain, which we linked to anticipatory, appetitive, and aversive cognitive states nature.com/articles/s4146…

So in our new study we used a similar approach to identify expression patterns across the brain (16 regions) AND across the lifespan (prenatal to 82 years old) via postmortem tissue from 57 human donors.

We found that OXTR expression begins to accelerate just before birth, with a peak level of expression occurring during early childhood (especially in males).

In particular, there was increased OXTR expression in the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus during early childhood

In particular, there was increased OXTR expression in the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus during early childhood

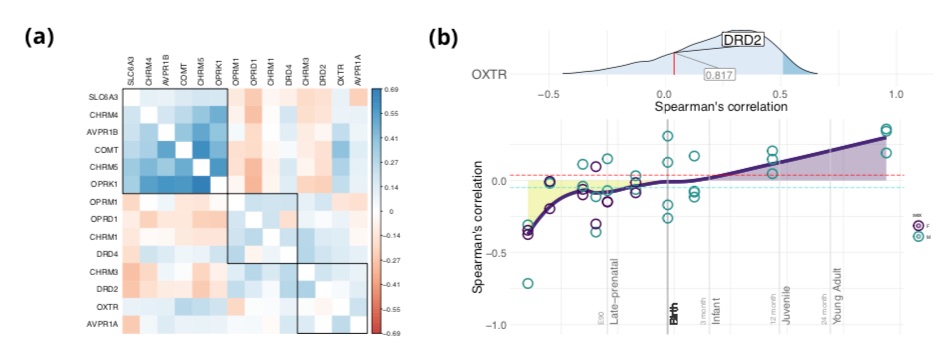

We also calculated the spatio-temporal correlation between OXTR and a geneset of interest from our previous work in adults, discovering a module of genes that co-express with OXTR both across the lifespan and across the brain (CD38, COMT, OPRK1, DRD2)

To assess the specificity of this result, we calculated the spatio-temporal relationship between OXTR and ALL available genes (n = 16659). The relationship with the dopamine receptor DRD2 was among the top 1.7% strongest relationships (b) and this was pretty stable over time (c)

To see if this pattern was a recent evolutionary feature, we performed the same analysis from rhesus macaque data across the lifespan, from the prenatal stage to early adulthood

Like our human analysis, we found an acceleration before birth, but no peak during early childhood.

We also did not find a strong relationship between OXTR and DRD2 gene expression, like we saw in the human data

We also did not find a strong relationship between OXTR and DRD2 gene expression, like we saw in the human data

Then, we went MUCH further back down the evolutionary tree using phylostratigraphy, which can identify which branch of the phylogenetic tree the original ancestor of a gene first appeared

As gene modules with high co-expression in the brain are related to molecular functions, we created a geneset containing the genes with the 100 strongest spatio-temporal correlations with OXTR

We found that most genes associated with OXTR expression are evolutionary ancient (the oldest phyostratum is cellular organisms)

We then calculated a transcriptional age index (TAI) for sixteen brain regions across five ontogenetic stages

to better understand the role of older vs. newer genes from this OXTR geneset module in brain development.

Here's more info about the TAI: rdcu.be/cjeYQ

to better understand the role of older vs. newer genes from this OXTR geneset module in brain development.

Here's more info about the TAI: rdcu.be/cjeYQ

For all brain regions except the striatum (STR) and cerebellar cortex (CBC), the transcriptome of the OXTR top 100 geneset was older during the prenatal stage, compared to later stages

What also stood out here was that the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus (MD), which regulates decision making and behavioral flexibility, had a younger transcriptional age compared to all other regions from infancy to adulthood

To identify the source of this younger transcriptional age for MD, we calculated the *cumulative* contribution of genes from each phylostrata for MD, revealing that genes that first emerged during the 6th (eumetazoa) and 7th (bilateria) phylostrata has the largest contribution

What's interesting here is that complex nervous systems first emerged during the bilateria phylostrata and the differentiation of organs and tissues emerged during the eumetazoa phylostrata, in which eumetazoans used peptide signalling for cross-tissue communication

Next, we investigating the functional significance of spatio-temporal expression patterns of genes strongly

coupled with OXTR, finding enrichment in GWAS-derived genes for bone fracture in osteoporosis

coupled with OXTR, finding enrichment in GWAS-derived genes for bone fracture in osteoporosis

Now bone isn't the first thing that comes to mind when it comes to oxytocin, but bone remodelling issues have been reported in autism, which has been associated with oxytocin system dysfunction pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17879151/

We also looked at the enrichment of this geneset in thirty tissue types across the body, discovering up-regulated differentially expressed genes in brain and lung tissue

So what are the health implications of the OXTR gene expression patterns across the lifespan?

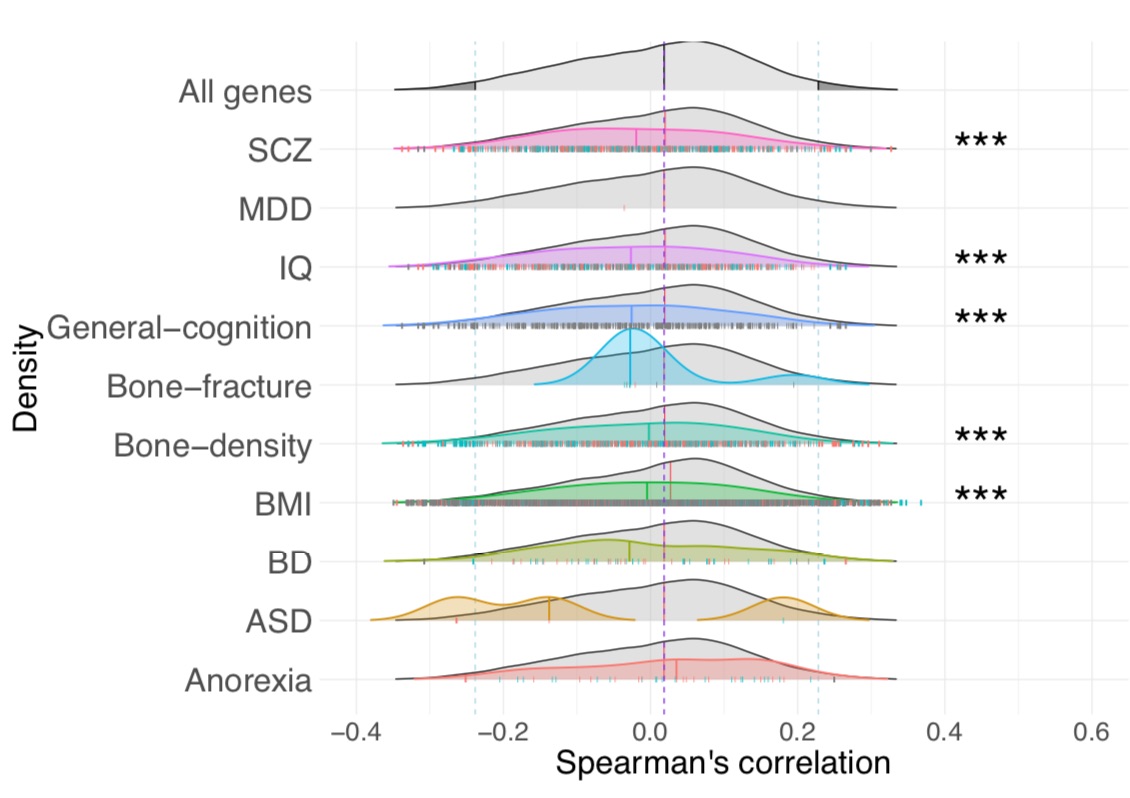

To answer this, we extracted genesets from various psychiatric and psychological phenotypes

To answer this, we extracted genesets from various psychiatric and psychological phenotypes

We found enrichment of the OXTR lifespan expression pattern in schizophrenia, IQ, general cognition, bone density, and BMI.

Finally, we confirmed that OXTR had high spatio-temporal differential stability from donor-to-donor (genes with differential stability scores in the top 50% of all genes are considered to be conserved) in humans and macaques

All the code to reproduce our analysis and figure can be found here gitlab.com/jarek.rokicki/…

This also includes instructions for data download too, we automated this as much as possible

This also includes instructions for data download too, we automated this as much as possible

This was a huge effort from @jarekrokicki! Big shout out to the rest of the co-author team too.

Please get in touch via twitter or email if you have any feedback

Please get in touch via twitter or email if you have any feedback

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh