"Be realistic: demand the impossible!" — a slogan coined by the Parisian anarchists of May 1968 — is actually a surprisingly good principle to setting effective targets (🧵):

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

There's a smart, cynical thing to say when presented with a series of ambitious-sounding long-term targets like those presented at last week's #ClimateSummit:

Talk is cheap. Action is expensive. Climate promises are always broken.

theguardian.com/environment/20…

Talk is cheap. Action is expensive. Climate promises are always broken.

theguardian.com/environment/20…

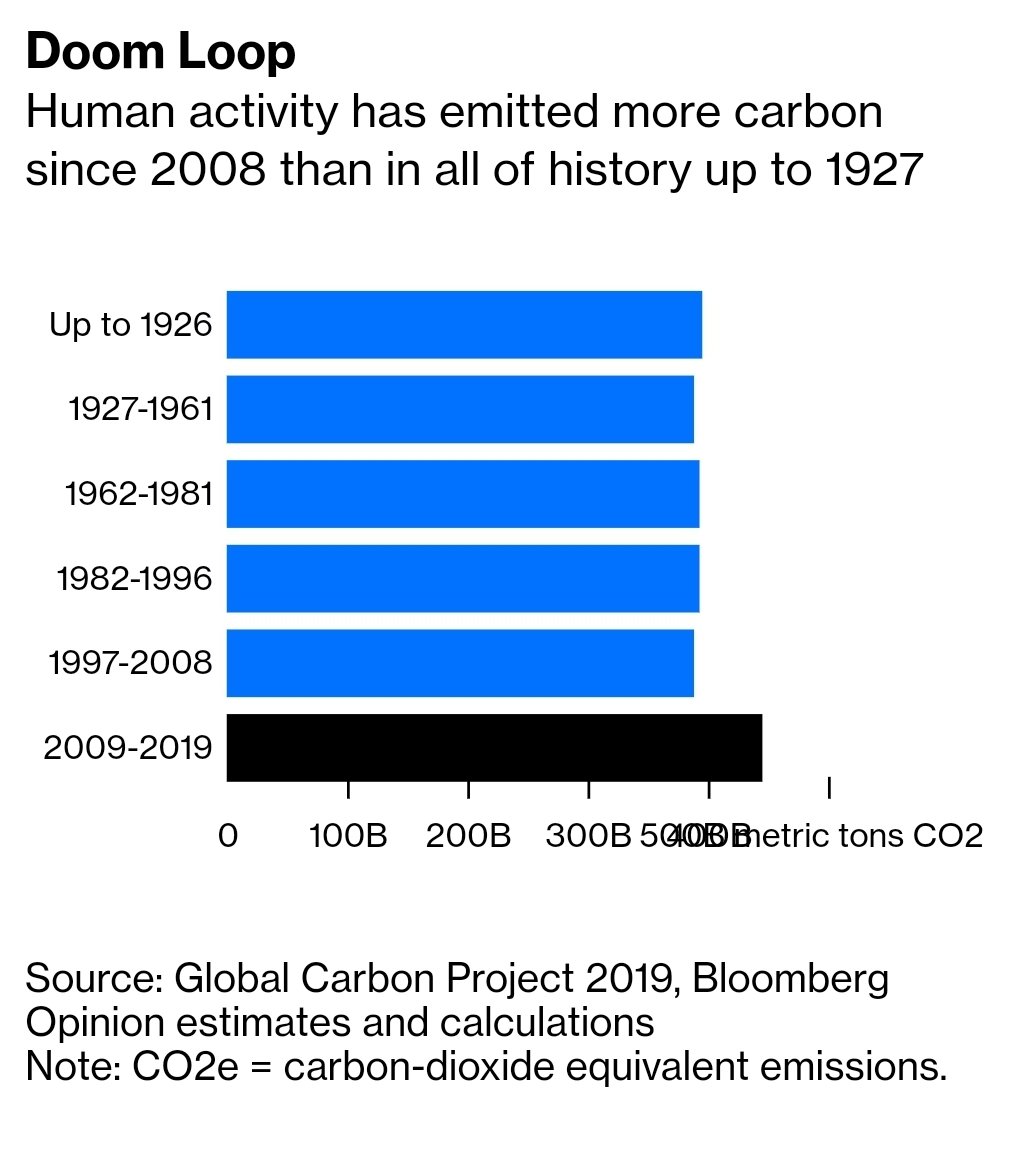

About a third of all the greenhouse emissions in history happened since the 1997 Kyoto protocol.

That doesn't sound like international agreements are very effective!

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

That doesn't sound like international agreements are very effective!

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

Or to quote @GretaThunberg's words to a Congressional committee last week, "We’re not so naive that we believe that things will be solved by countries and companies making vague, distant insufficient targets."

An odd thing about that quote is that it could have come out of a standard management text on goal-setting.

There's a lot of evidence that the opposite formulation to "vague, distant and insufficient" — "specific, time-limited and challenging" — is strikingly effective.

There's a lot of evidence that the opposite formulation to "vague, distant and insufficient" — "specific, time-limited and challenging" — is strikingly effective.

The key text here was written at the time of the Paris 1968 protests by a figure who couldn't be more different: Edwin A. Locke, a psychologist and devotee of Ayn Rand.

His crucial insight was that people are *more*, not less, likely to hit goals if they seem difficult.

His crucial insight was that people are *more*, not less, likely to hit goals if they seem difficult.

This is one of the better-evidenced findings in management studies and libraries of business books have been written based upon it, but it's striking how rarely we acknowledge its importance in public policy terms.

researchgate.net/publication/23…

researchgate.net/publication/23…

I think this is really important now because the *philosophy of goal-setting* that world leaders subscribe to will determine the sorts of targets they set on climate, and the sorts of outcomes that result.

On one extreme I'd put the Chinese government, which is very into setting goals through five-year plans etc but is also obsessed with the idea that targets *must* be achieved, and as a result tends to be quite conservative to avert the risk of failure.

At the other extreme I'd maybe put India, where politicians often proclaim very bold targets (such as ending coal imports by 2017, or installing 175GW of renewables by 2022) that aren't met but treat it as no big deal.

Most other nations are somewhere in the middle.

Most other nations are somewhere in the middle.

Now, I think we've learned this history all wrong. If you look at the track record of climate targets, IMO it's not a litany of broken promises but a tale of achievement that's increased as people's ambitions have grown bolder.

Take Kyoto. It's conventional to regard it as a failure and to mark this as evidence against target-setting.

But actual emissions reduction from parties to Kyoto was 22.6% over the relevant period, way ahead of the 5% target.

unfccc.int/news/kyoto-pro…

But actual emissions reduction from parties to Kyoto was 22.6% over the relevant period, way ahead of the 5% target.

unfccc.int/news/kyoto-pro…

The problem with Kyoto wasn't that *targets don't work*.

It was that *the biggest emitters didn't commit to targets*.

Kyoto certainly got an assist from the collapse of heavy industry in the former Soviet bloc, but especially in Europe its track record was pretty good.

It was that *the biggest emitters didn't commit to targets*.

Kyoto certainly got an assist from the collapse of heavy industry in the former Soviet bloc, but especially in Europe its track record was pretty good.

One idea of a pie-in-the-sky target I remember from 20 years ago is the renewable portfolio standards and feed-in tariffs that the U.S. and Europe set up to encourage deployment of wind and solar.

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

It's implicit in the design of these policies that renewables stood no real chance of being commercially competitive with fossil fuels.

That forecast couldn't have been more wrong: almost every megawatt of new power investment these days is wind or solar.

That forecast couldn't have been more wrong: almost every megawatt of new power investment these days is wind or solar.

During the 2010s, with no real support from the policy environment outside Europe, power generation emissions actually tracked pretty close to the "below 2 degrees" scenario the @IEA had laid out in 2009:

Just to take one more example: That 175GW India renewables target has been scoffed at by every expert since it was set out in 2015.

The Indian government hasn't helped its case by allowing large hydro to be included at a late stage, massaging the numbers. energy.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/renewable…

The Indian government hasn't helped its case by allowing large hydro to be included at a late stage, massaging the numbers. energy.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/renewable…

And yet, and yet: In spite of a pretty unhelpful policy backdrop, not to mention a record recession and ongoing pandemic, renewables operating and under construction plus those being bid for come to 170GW, and we're still nearly two years out.

mnre.gov.in/img/documents/…

mnre.gov.in/img/documents/…

One tendency is to look at that track record and see only the failure: "India promised 175GW by 2022 and may only hit that number in 2024."

But I think that's to ignore how far even that achievement is past the bounds of what was thought possible.

But I think that's to ignore how far even that achievement is past the bounds of what was thought possible.

I've been quite critical of China on this front for precisely that reason. While the net zero by 2060 target sounds bold, the government are extremely cautious about binding their hands by making ambitious near-term targets: bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

The risk there is that China undershoots what it's capable of doing on decarbonization for fear of setting a goal that will challenge it, such as increasing annual renewables installations to a level that will drive coal off the grid rapidly:

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

Ironically, one of the main things that IMO constrains China from setting a bolder near-terms emissions target is that it's obsessed with setting (and hitting) growth targets, and polluting heavy industry still provides a powerful sugar high to GDP.

But that's just a testament to the remarkable power of goal-setting. The problem in China is that the wrong objectives are still being prioritized, as they were in other countries until recently.

Personally, I'm optimistic that the current round of promises aren't just words.

Challenging goals motivate us to find ways to achieve them.

We shouldn't limit the scope of our ambitions by negotiating with ourselves before we even make a commitment.

Challenging goals motivate us to find ways to achieve them.

We shouldn't limit the scope of our ambitions by negotiating with ourselves before we even make a commitment.

That's why we people need to keep the pressure on and push political leaders to raise their ambitions again. The easiest way to miss a goal is to not aim for it in the first place. (ends)

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

Important point here.

Science provides such a clear picture of what needs to be done that targets end up being ambitious and challenging by default:

Science provides such a clear picture of what needs to be done that targets end up being ambitious and challenging by default:

https://twitter.com/felipe_deleon/status/1386189688898211840?s=19

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh