How much warming is committed, "locked in", or "in the pipeline" has long been a source of confusion.

In a new @CarbonBrief explainer we take a deep dive into what would happen to the climate once we reach net-zero emissions.

A thread: 1/19

carbonbrief.org/explainer-will…

In a new @CarbonBrief explainer we take a deep dive into what would happen to the climate once we reach net-zero emissions.

A thread: 1/19

carbonbrief.org/explainer-will…

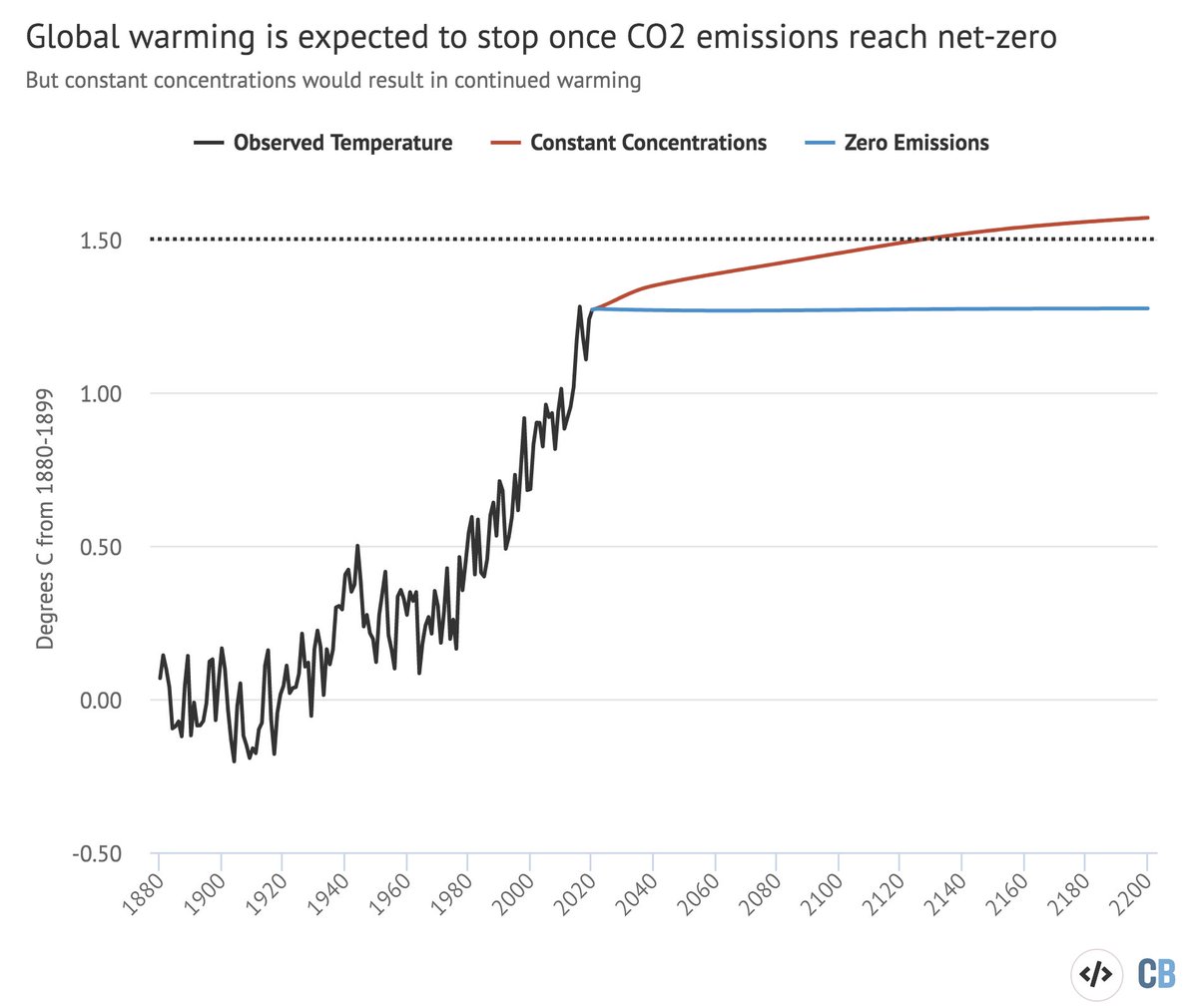

Much of the confusion around committed warming comes from a conflation of two different scenarios: one where atmospheric CO2 is held at constant levels (say, ~414 ppm today), and one where all our emissions go to zero. 2/

Until the mid-2000s, many climate models were unable to test the impact of emissions reaching zero. This is because they did not include biogeochemical cycles – such as the carbon cycle – and could not effectively translate emissions of CO2 into atmospheric CO2 concentrations. 3/

There were a lot of studies looking at what happens in models when you keep concentrations constant – which results in 0.4C to 0.5C additional warming over the coming centuries – but few looking at what happens if emissions go down to zero. 4/

However, in the late 2000s with papers like this one from Matthews and @KenCaldeira began to test what happens in zero emissions scenarios. They found that – unlike in the case of constant concentrations – zero emissions result in flat future temps. agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.10… 5/

In a zero emissions scenario there is some additional warming in the system as oceans continue to heat up, this is counterbalanced by cooling due to falling atmospheric CO2 concentrations. These conveniently balance each-other out, leading to flat future temps. 6/

More recently, an analysis of 18 different Earth System Models in the Zero Emissions Commitment Model Intercomparison Project (ZECMIP) came to the same conclusion: additional ocean warming is balanced out by falling CO2 and future temps are flat in most models: 7/

There is some uncertainty here; while most models project around zero warming in the fifty years after zero emissions, a few have as much as 0.3C cooling or 0.3C warming. 8/ biogeosciences.net/17/2987/2020/

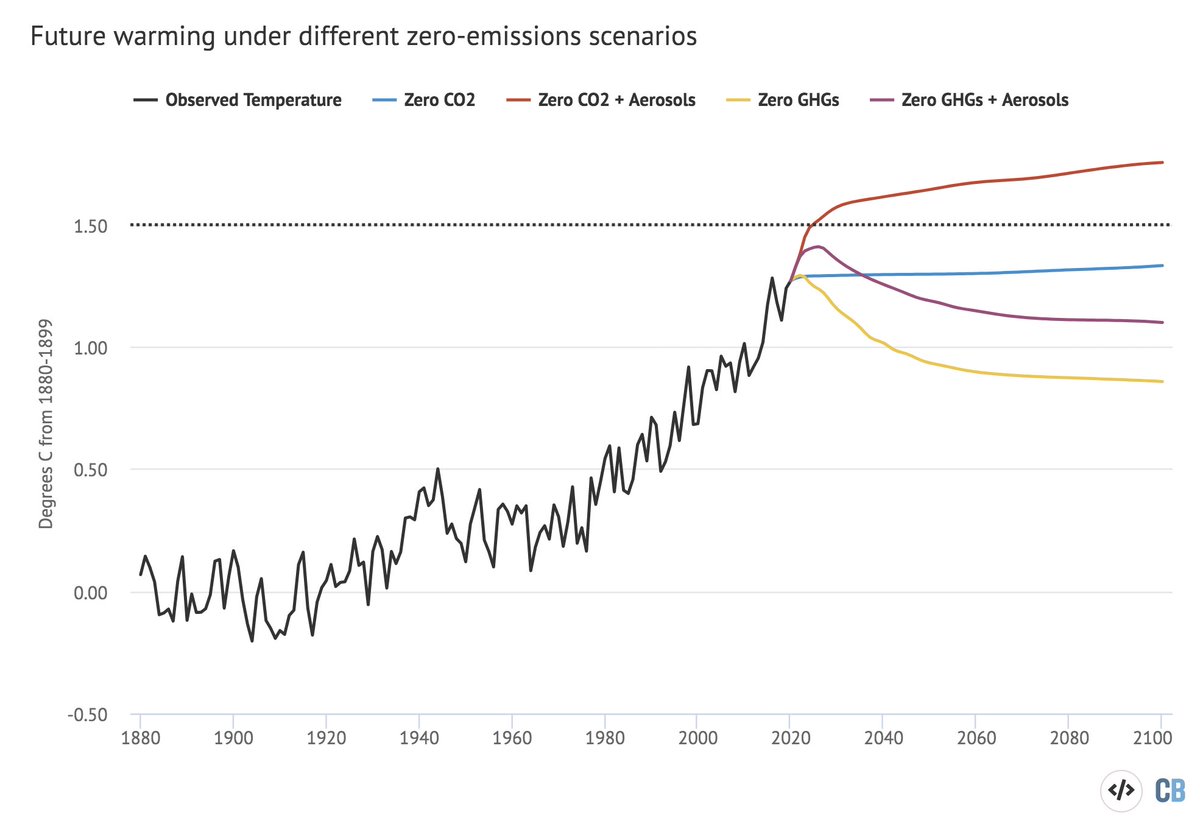

There are also some uncertainties around what we mean by zero emissions. While zero CO2 emissions would likely result in flat temps holding everything else equal, there are a lot of other human emissions than affect the climate. 9/

The recent @IPCC_CH SR15 report looked at four different versions of zero emissions: zero CO2, zero CO2 and aerosols, zero GHGs (including CO2), and zero GHGs and aerosols: 10/

Human emissions of aerosols have a strong cooling effect on the planet, though there are large uncertainties as to big. Aerosols also have a relatively short atmospheric lifetime and, if emissions cease, the aerosols currently in the atmosphere will quickly fall back out. 11/

As a result, the world would be around 0.4C warmer if CO2 and aerosol emissions go to zero, compared to zero CO2 emissions alone. In this scenario (red line), the world would likely exceed the 1.5C target, reaching around 1.75C by 2100. 12/

Other GHGs are also important drivers of global warming. Human-caused emissions of CH4, in particular, account for about a quarter of the historical warming that the world has experienced. 13/

Unlike CO2, CH4 has a short atmospheric lifetime, such that emissions released today will mostly disappear from the atmosphere after 12 years. This means the world would cool ~0.5C by 2100 if all GHG emissions fell to zero. 14/

Finally, if all human emissions that affect climate change fall to zero – including GHGs and aerosols – then the IPCC results suggest there would be a short-term 20-year bump in warming followed by a longer-term decline. 15/

In this case (zero GHGs and aerosols), the cooling from stopping non-CO2 GHG emissions more than cancels out the warming from stopping aerosol emissions, leading to around 0.2C of cooling by 2100, albeit with large uncertainties from aerosols. 16/

There is also a potential for natural variability to play a role in future warming, even under a zero emissions future. For example, see this discussion of a recent paper by Zhou et al (and @AndrewDessler):

https://twitter.com/hausfath/status/1346160314924974081?lang=en17/

The studies in this piece all look at the effects of zero-emissions scenarios today. If, however, zero emissions were to occur later in the century, there is the potential to lock in more carbon-cycle feedbacks – such as melting permafrost – than under current global temps. 18/

Finally, while current best estimates suggest that temperatures will stabilize in a zero-emissions world, that does not mean that all climate impacts would cease to worsen. Melting glaciers and ice sheets and rising sea levels all occur slowly and lag behind surface temps. 19/19

Ultimately, these findings are good news. A world where we can likely stop warming by getting our emissions to zero is one where we have a lot more control over climate outcomes. It is not too late to avoid dire impacts of warming if we can reduce emissions quickly. 20/19

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh