Had a good discussion today on @TheWorld with @ProfTimJackson about the extent to which we can both have economic growth and mitigate climate change.

pri.org/file/2021-04-3…

Lets dig into the debate in a quick thread: 1/18

pri.org/file/2021-04-3…

Lets dig into the debate in a quick thread: 1/18

First, there are a lot of places where Tim and I agree. We agree on the need to replace fossil fuels with clean energy, and to get emissions down to zero. We agree GDP is a poor proxy for human wellbeing, and that modern economies have huge problems with inequality. 2/

Where we differ is on whether technology allows us to "decouple" economic activity from its environmental impact. 3/

I'm a technological optimist. I think that we can get the services we enjoy from fossil fuels today – heating our homes, driving our cars, consuming good food, buying consumer goods – using clean energy sources like solar, wind, nuclear, hydro, and geothermal. 4/

For example, electric cars can replace internal combustion engines. Veggie based alternatives and lab-grown meats can replace many of the billion cows we have today. 5/

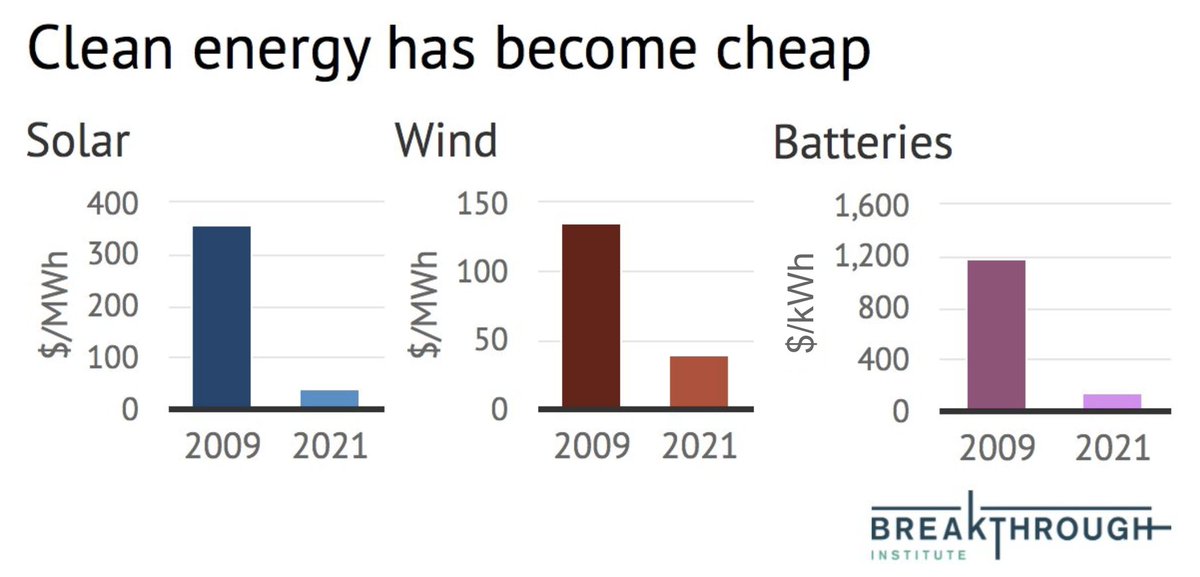

When Obama came into office in 2009 solar panels were $350 per MWh; when Biden came into office in 2021 they were $35 per MWh, a factor of ten drop. During the same time battery prices have also fallen by a factor of ten, and wind by a factor of three. 6/

I think we can continue theses trends, and ultimately reach zero emissions by replacing all of our fossil fuels with clean energy while at the same time building human prosperity, particularly in poor and middle income countries. 7/

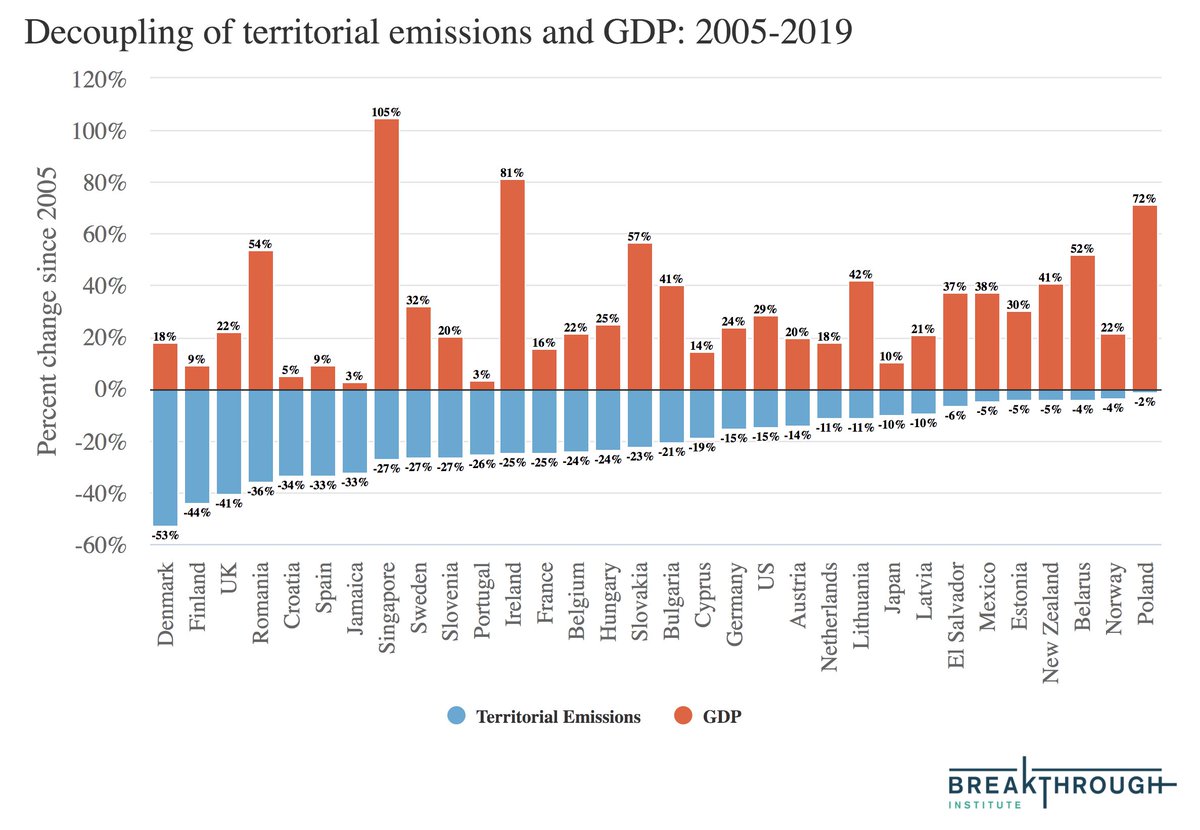

Rich countries – members of the OECD – have on aggregate reduced their emissions over the past 15 years. OECD country emissions peaked their emissions in 2005, and in 2019 had reduced them by 12% (much more in 2020, but we won't count that). 8/

Accounting for CO2 embodied in trade (e.g. goods imported from China), emission reductions in OECD countries were down 11% since 2005. In a recent analysis we found that 32 countries have now absolutely decoupled their emissions from economic growth. thebreakthrough.org/issues/energy/… 9/

Even China – which drove much of the global growth in emissions in the 2000s – is quickly on its way to absolute decoupling. Per-capita emissions have already absolutely decoupled and are flat, while total emissions are on track to peak around 2025. 10/

Most future emissions in the 21st century will come from poor to middle income countries trying to reach the same living standards that we take for granted. We need to both accelerate the reduction of rich country emissions... 11/

... and make clean energy cheap so that poorer countries can leapfrog fossil-fuel driven development, and reach the level of prosperity that we take for granted without destroying the climate in the process. 12/

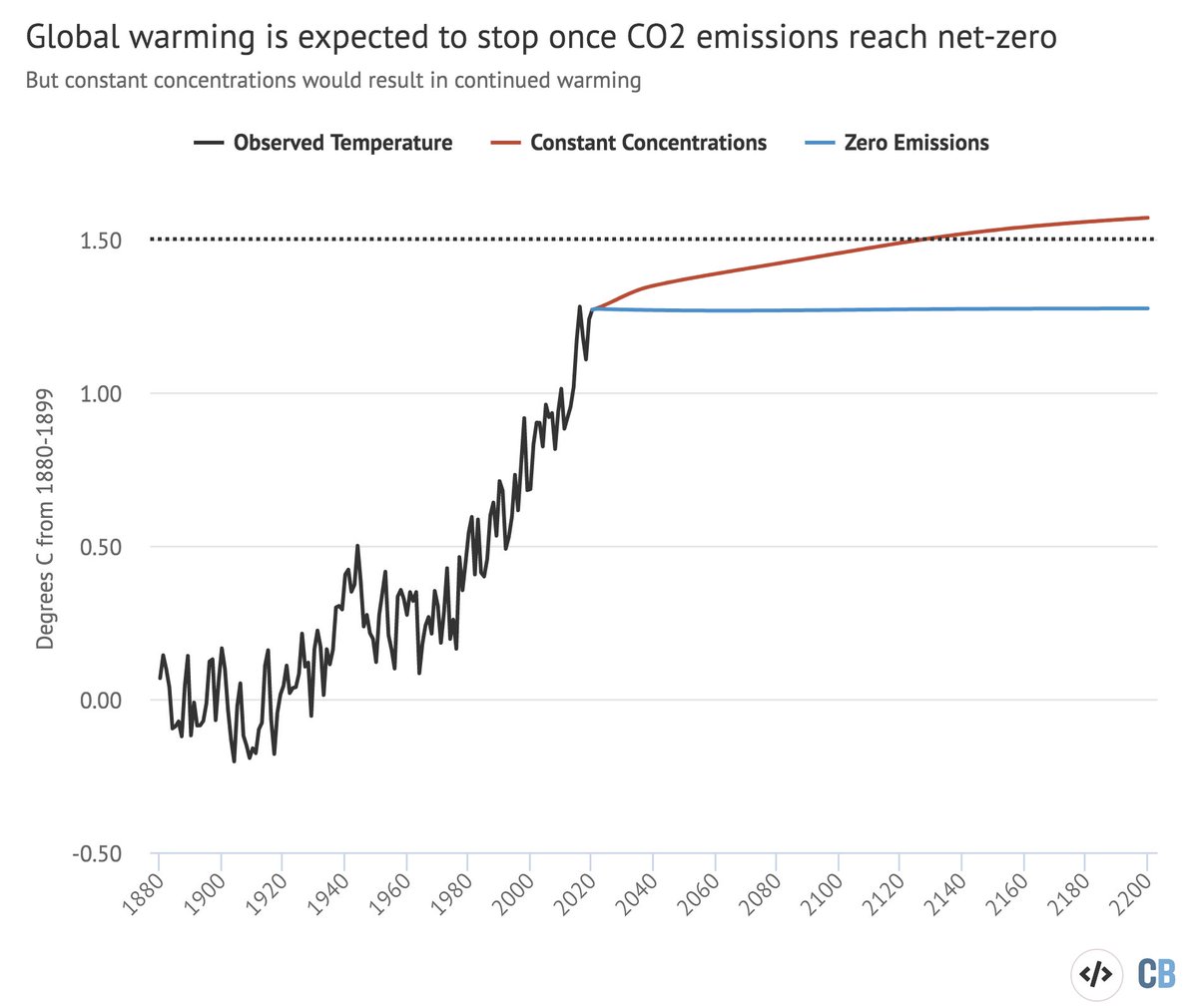

Now, decoupling emissions from growth is only the first and easiest step to getting to net zero emissions by the middle of the 21st century, which is what is needed to limit warming to well-below 2C in line with the Paris Agreement goals. 13/

But I argue that its quite possible to get the global to zero emissions while building human prosperity – particularly in poor to middle income countries. 14/

This is in line with what we find in the energy system models we use to show how the world might limit warming to well-below 2C (or to 1.5C) in the IPCC. Every single pathway that reaches zero emissions has the global economy between 3x and 10x larger than today by 2100. 15/

In fact, the pathway that has the easiest time meeting Paris Agreement goals – SSP1 – has the second highest level of economic growth of any of the five pathways that we use. 16/

These energy system models are just that – models – but they show that a pathway toward green growth is possible through the widespread deployment of clean energy technologies. 17/

Ultimately economic growth will stop in rich countries, due to diminishing returns and shrinking populations. However, with good policy and technology we can ensure that we can reach a prosperous, equitable, and zero-emissions future for everyone on the planet. 18/18

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh