In 1941, there was a real push to create a battle-ready PMP (Protective Mobilization Plan) army that would encompass both Ground and Air Forces.

At the time, and increasingly throughout the Interwar Years leading up to this time, the perception of Air Power among much of the general public was a bit overly optimistic when compared to the actual capabilities of the then-contemporary air forces.

In other words, the general public had a lot of faith that the air forces could do way more than they actually could at the time.

As mentioned earlier, the US Army Air Corps had about 20,000 men in 1939, and 1700 aircraft, all of which were obsolete.

In May 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called for the Army Air Corps to increase their aircraft to 50,000 and establish a production capacity that would create 50,000 aircraft per year. This was FDR reacting to German aggression in Europe.

And these numbers may seem a bit high, especially considering the state of the barely-existent military industrial complex throughout the Interwar Years. But from 1940 to 1945, we would end up procuring 230,000 aircraft.

A few weeks later, in July of 1940, Congress authorized the US Army Air Corps to have 54 groups with a total of 3149 aircraft. By March of 1941, this authorization was increased to 84 groups and 7799 aircraft.

And on 20 June 1941, the War Department reorganized the US Army Air Corps concept to create the new US Army Air Forces. The US AAF would be an autonomous organization within the War Department.

These changes reflected a desire to increase the role of Air Power in our National Strategy and there was a lot of importance woven into this effort to grow the AAF.

But there was no real consensus for how the Air Force would actually function in war.

At first, the War Department held the idea that the AAF’s primary function in war would be to support the Ground Forces on the battlefield.

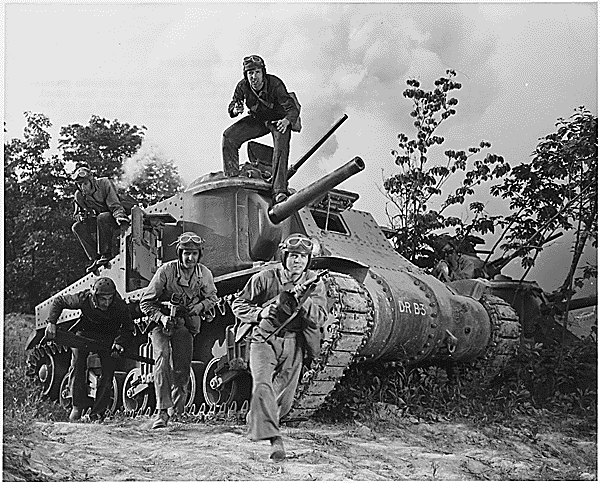

The War Department’s Training Directive for 1940-1941 called for Combined Arms – teamwork – between Infantry, Cavalry, Field Artillery, and the Army Air Corps.

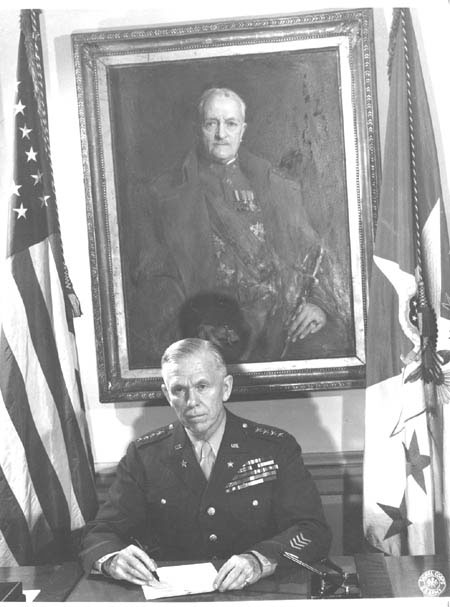

But George Marshall believed that the Air element needed to be able to conduct their own actions, not just coordinate with Ground Forces.

The US Army Air Corps produced their first Doctrine in 1926, after spending about eight years trying to figure out the best way to set realistic expectations for Air elements during a war.

The 1940 Field Manual (FM) 1-5 ‘Employment of the Aviation of the Army’ is actually believed to be the first time we used the term “Basic Doctrine”

But that “fundamental” Air Corps Doctrine from 1926 basically stated that airmen were “to aid the ground forces to gain decisive success” with modest recognition that the Air elements might be required for “special missions at great distances from the ground forces.”👀

This publication was revised in 1935, but remained the general Doctrine for Army Aviation from the time of original publication, 1926, until 1940. Progress is sometimes slow.

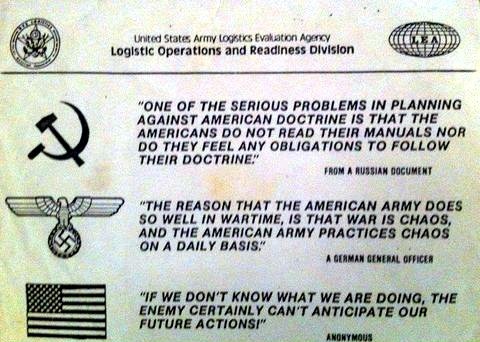

“Those airmen who believed in the potential of airpower as a decisive weapon were viewed as radicals by the balance of the Army.”

There was a desire within the US AAC to morph the US Army Air Corps into a separate / independent force within the United States military. Part of this stemmed from recognizing the need for centralized control of air units in order to better coordinate for combined arms.

The US Army Air Corps Tactical School moved from Langley Field, in Virginia, to Maxwell Field, in Alabama, in the summer of 1931. They began working to find ways the Air Corps could help reduce the likelihood “of the stalemate and bloodbath of trench warfare” seen in WWI.

The Air Corps Tactical School (ACTS) instructors prioritized concepts of winning a war quickly at the lowest cost possible – and this “cost” to the United States was considered “in terms of blood and treasure.”

There was, however, some contention between the airmen of the US AAC and the non-airmen of the US Army. Some historians have argued that this carried over to future generations and we still see elements of the argument:

“It is this paranoia that has been largely responsible for keeping modern airmen focused on ‘survival of the service’ rather than on airpower theories, operational doctrine, and cooperation in a joint world with other services.”

“It persists to this day. It is the single overriding intellectual feature of Air Force thinking.”

(This is from an article published in 1995 that discussed problems with USAF Doctrine from 1926-1995.)

(This is from an article published in 1995 that discussed problems with USAF Doctrine from 1926-1995.)

After WWII, General Henry “Hap” Arnold said:

“Any Air Force which does not keep its doctrines ahead of its equipment, and its visions far into the future, can only delude the nation into a false sense of security.”

“Any Air Force which does not keep its doctrines ahead of its equipment, and its visions far into the future, can only delude the nation into a false sense of security.”

A new FM 1-5 “Employment of the Aviation of the Army” was published in April of 1940, and it had been written under the guidance of Carl Spaatz, a Lieutenant Colonel and one of those US AAC ‘heretics’.

(This is actually the 1943 manual, I think, but it has the right title.)

(This is actually the 1943 manual, I think, but it has the right title.)

This new FM 1-5 was intended to replace the previous Air Corps Doctrine of the Interwar Years, but it was little more than an expansion of the TR 440-15 publication from 1935. The Army Air Corps’ desire to use strategic bombing largely went unmentioned.

Once we reached North Africa in 1942, it would become clear that we had arrived “with an abundance of ignorance!” as so eloquently put by Lieutenant General Elwood “Pete” Quesada. (This guy)

This experience would lead to the publication of FM 100-20, ‘Command and Employment of Air Power’, published in July of 1943, based on a single air campaign “and written in the Army’s field service regulations series of publications…”

(I think this one is also from 1943.)

(I think this one is also from 1943.)

“The most notable feature of this new manual to most Army officers was the firm announcement that air and ground forces were coequal and interdependent.”

“This was less a declaration of independence by the @usairforce … and more the announcement of the War Department’s recognition of changed operational conditions imposed by the reality of war.”

If you're just tuning in or you've missed any of the previous threads, you can find them all saved on this account under ⚡️Moments or with this direct link twitter.com/i/events/13642…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh