One term I worry that we (as a public health community) have mis-messaged during the pandemic:

"herd immunity threshold"

A non-technical thread on why this is not "% of the population that needs to be vaccinated for us to return to life as normal while eradicating COVID-19"...

"herd immunity threshold"

A non-technical thread on why this is not "% of the population that needs to be vaccinated for us to return to life as normal while eradicating COVID-19"...

Disclaimer to the experts: This is for a non-expert audience.

Let's start with the virus that's currently circulating, and estimate roughly that - with no vaccine, no immunity, and "life as normal" - this person would infect ~5 other people before recovering (or dying).

Let's start with the virus that's currently circulating, and estimate roughly that - with no vaccine, no immunity, and "life as normal" - this person would infect ~5 other people before recovering (or dying).

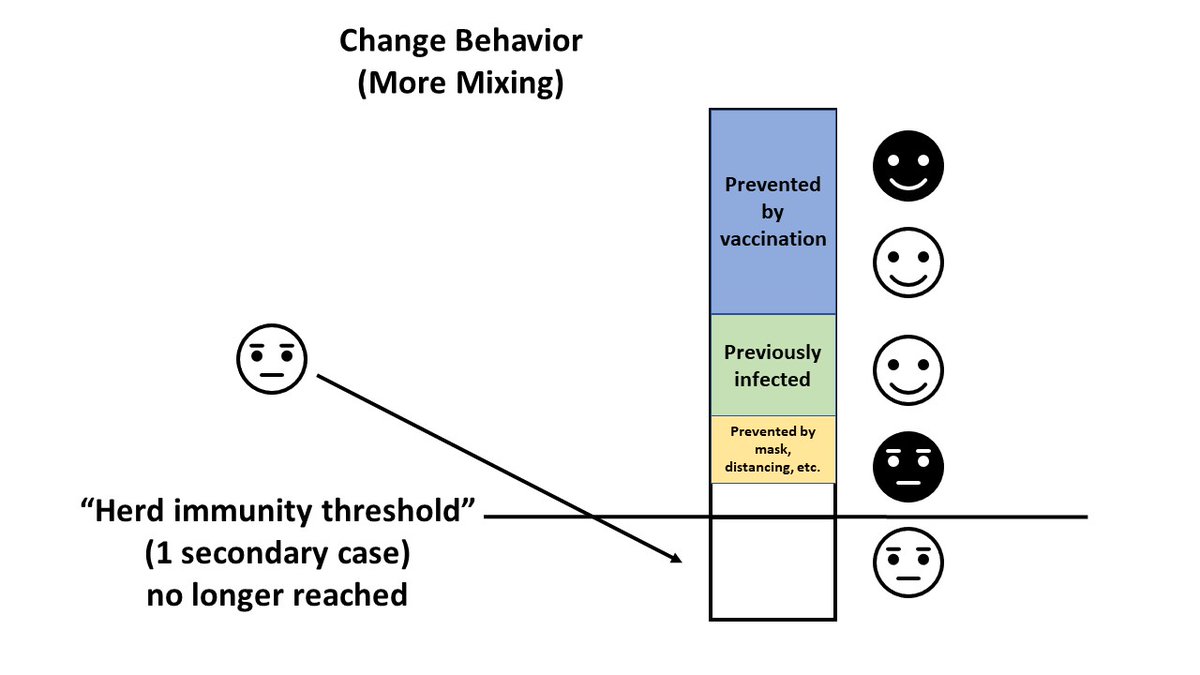

Next, let's take a situation similar to the USA. Out of these 5 possible people infected, 2 might be vaccinated; 1 out of the remaining 3 might be someone who's already have had COVID; and 1 of the remaining 2 might be prevented by current behaviors (masks, distancing, etc).

This would lead to, on average, each person with COVID-19 infecting 1 other person. Meaning the epidemic will be *stable* (and decline very slowly as more people get infected).

This is the "herd immunity threshold". Note that case counts are falling ever-so-slightly. Not zero.

This is the "herd immunity threshold". Note that case counts are falling ever-so-slightly. Not zero.

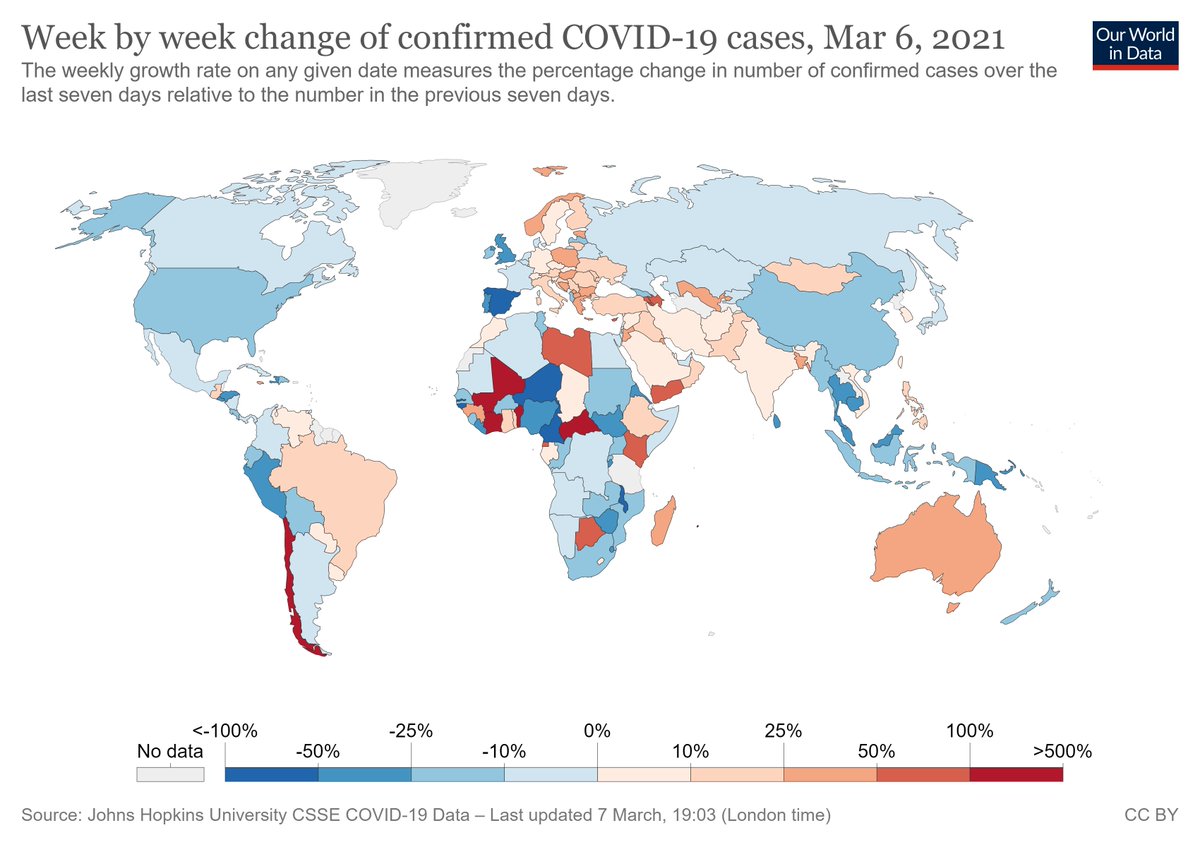

A key thing to note - while we may be at this stable level even now in places like the USA, case counts can easily rise again ("above the herd immunity threshold") if we relax behaviors such as distancing & mask-wearing too quickly.

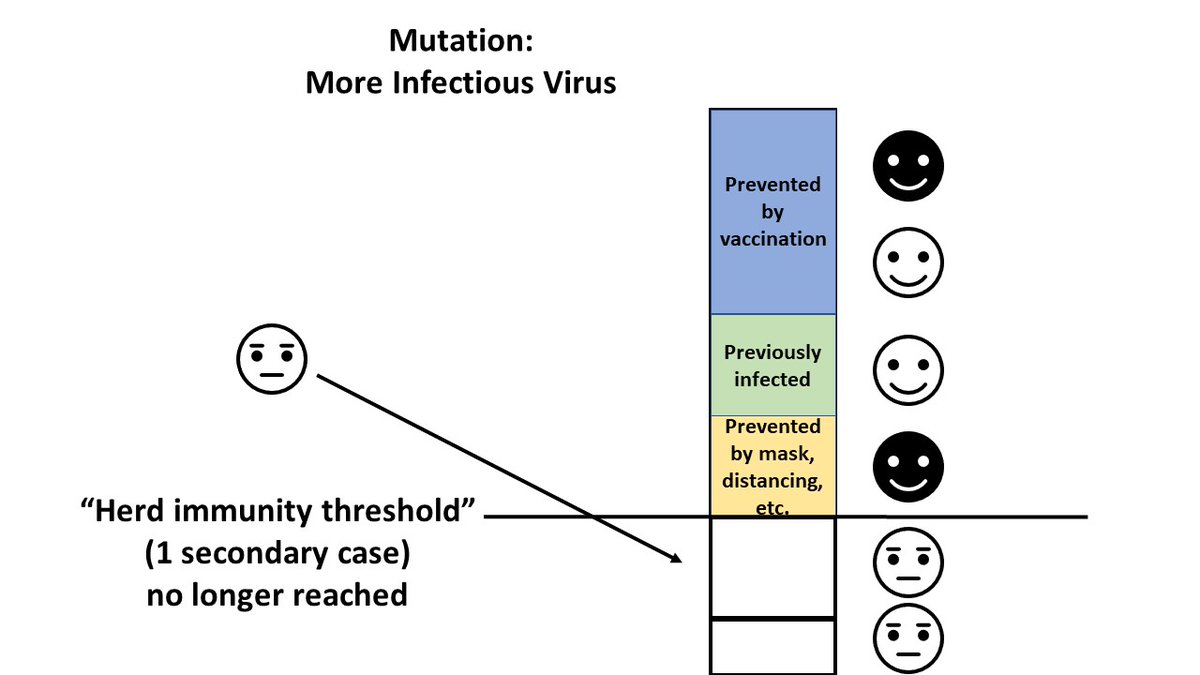

The same thing can (and will) happen gradually over time as the virus mutates to become more infectious (for example, if the average person with COVID-19 would infect 6 people rather than 5, in the absence of any immunity and "life as normal").

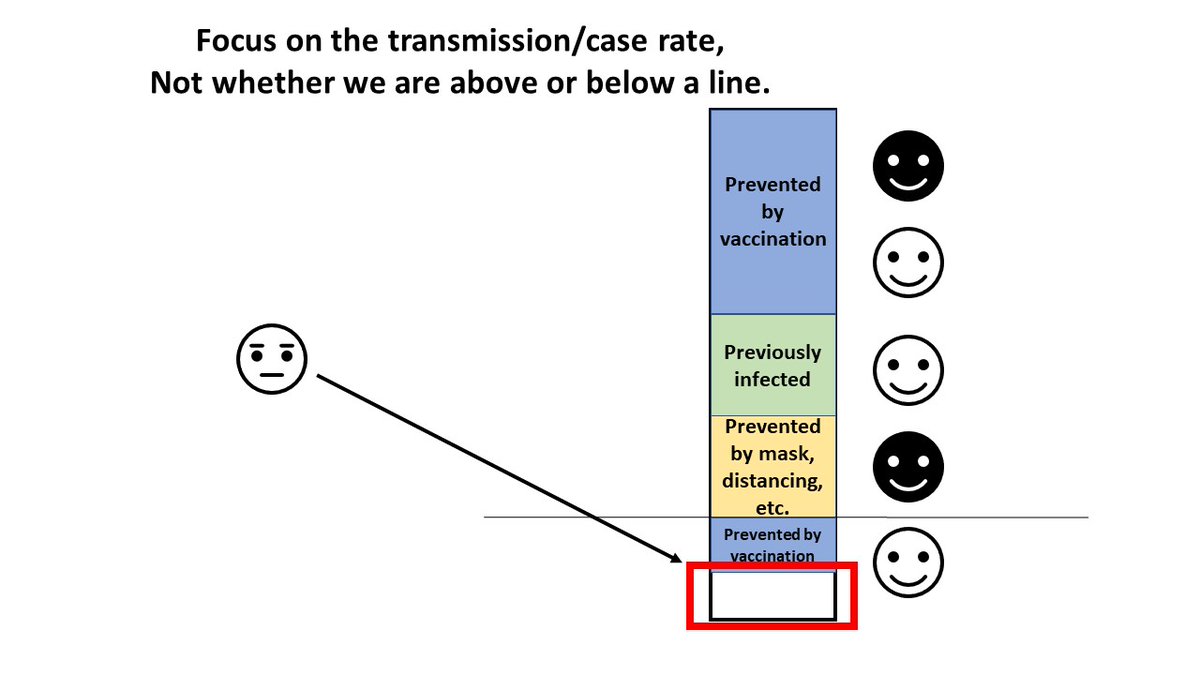

On the flip side, if we vaccinate people faster, we reduce the number of cases (and deaths) faster.

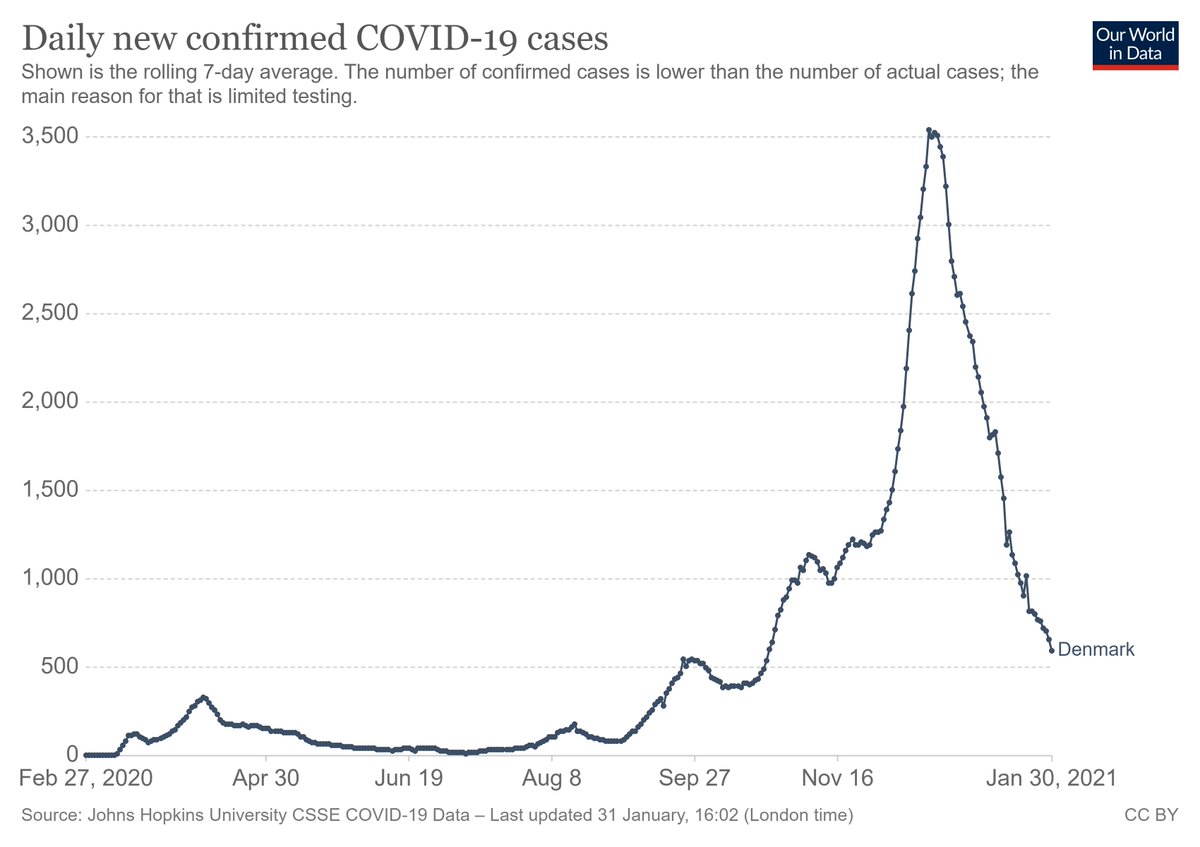

It's not about getting to a threshold where the epidemic is stable, it's about how fast we can get the epidemic under control - meaning going *beyond* the herd immunity threshold.

It's not about getting to a threshold where the epidemic is stable, it's about how fast we can get the epidemic under control - meaning going *beyond* the herd immunity threshold.

Once again - we should be focusing on the *number of cases* (and how fast that number is falling), not on whether we are above or below a specific threshold.

Asking "have we reached the herd immunity threshold" is similar to asking "are cases going up or down right now"?

Asking "have we reached the herd immunity threshold" is similar to asking "are cases going up or down right now"?

It's also important to remember that we are talking about "the average contacts of people with COVID-19 today," not "the average person".

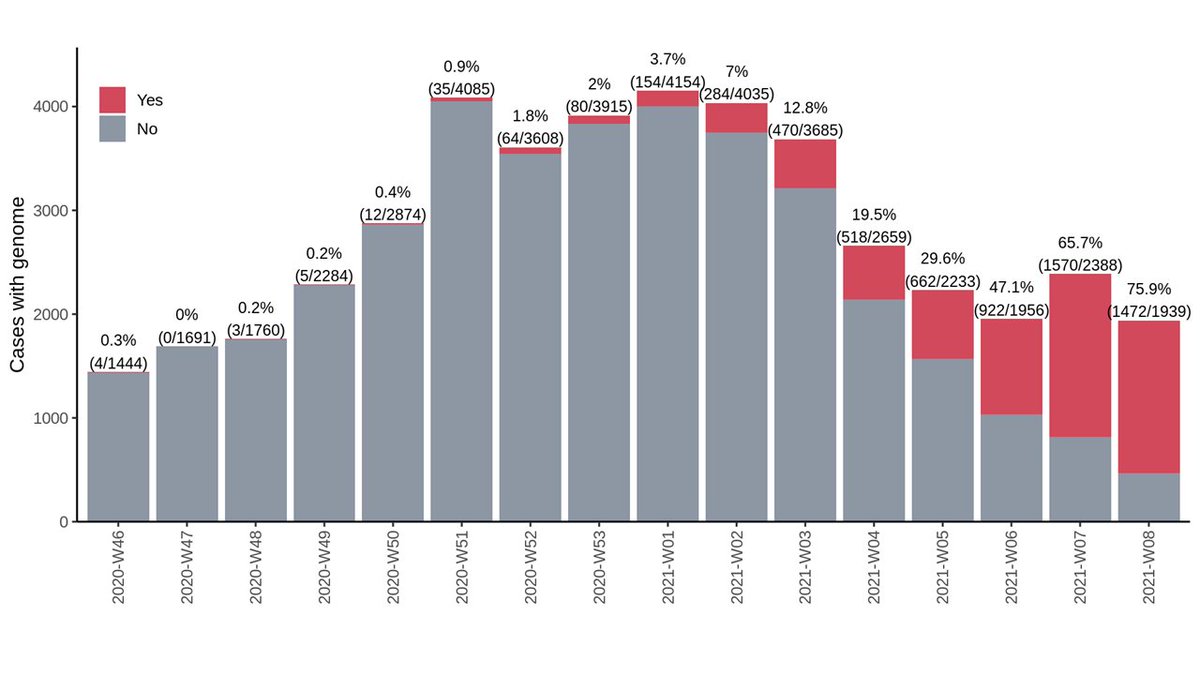

Even though 40% of the population might be vaccinated, for example, this doesn't mean that 40% of current COVID-19 contacts are vaccinated.

Even though 40% of the population might be vaccinated, for example, this doesn't mean that 40% of current COVID-19 contacts are vaccinated.

As a result, simple calculations of "XX% of people must be vaccinated to reach herd immunity" may be over-optimistic (e.g., if the average COVID-19 contact is less likely to be vaccinated or distancing) or pessimistic (if they are more likely to have been infected already).

Take-home messages:

1) Focus on the case count, not on reaching a threshold.

2) The more people who are vaccinated, the better.

3) Activities like wearing masks & minimizing large indoor gatherings still have an important effect.

4) Progress is always slow, but it is being made!

1) Focus on the case count, not on reaching a threshold.

2) The more people who are vaccinated, the better.

3) Activities like wearing masks & minimizing large indoor gatherings still have an important effect.

4) Progress is always slow, but it is being made!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh