Great new paper by @KirstenZickfeld on the asymmetry of the effects on atmospheric concentration and temperatures between carbon additions and removals. She has an accessible explainer of the findings over at @CarbonBrief: carbonbrief.org/guest-post-why…

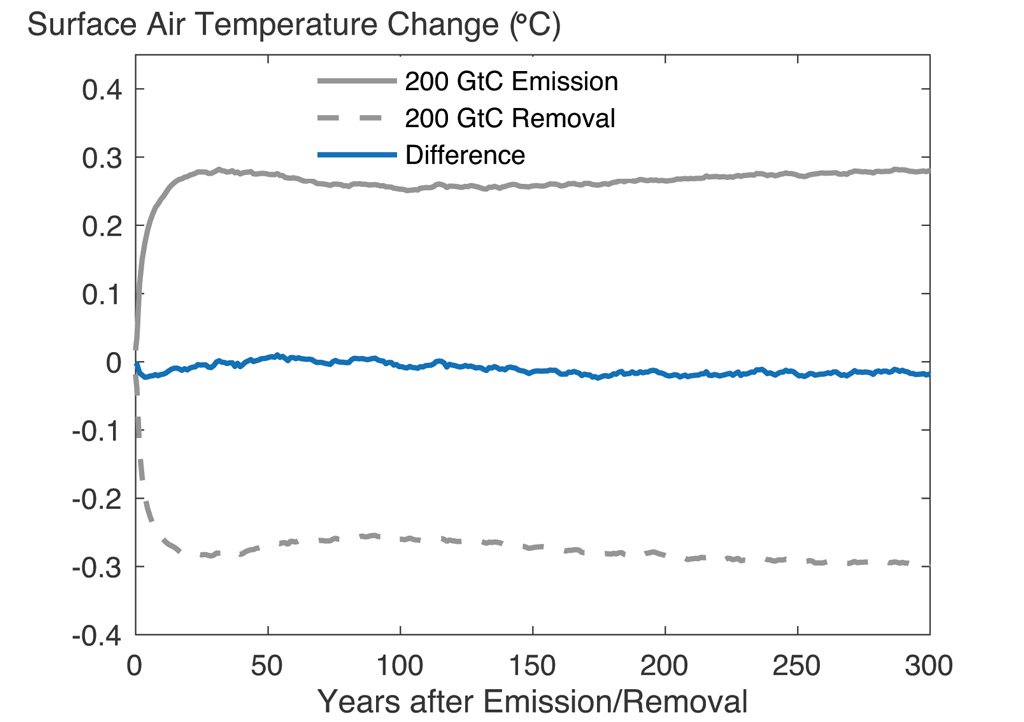

In short, they find that removing CO2 from the atmosphere is 3% to 18% less effective at reducing concentrations than adding it was in the first place, becoming less effective as more is removed. Thankfully the asymmetry for temperature are smaller – only 2% to 7% less:

None of this should suggest that carbon removals are not effective or needed; even if they were 20% less effective (at the extreme) than emissions additions, they would still be key to offset a long tail of hard to decarbonize activities.

Rather, we need to account for asymmetry in our modeling and deployment scenarios. Removing a ton of CO2 from the atmosphere reduces atmospheric CO2 by a bit less than adding a ton of CO2 to the atmosphere increases it (and, importantly, the airborne fraction applies to both!).

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh