A🧵on studies attempting to infer the date of origin of the virus

<epistemic status: gathering datapoints, not drawing conclusions>

<epistemic status: gathering datapoints, not drawing conclusions>

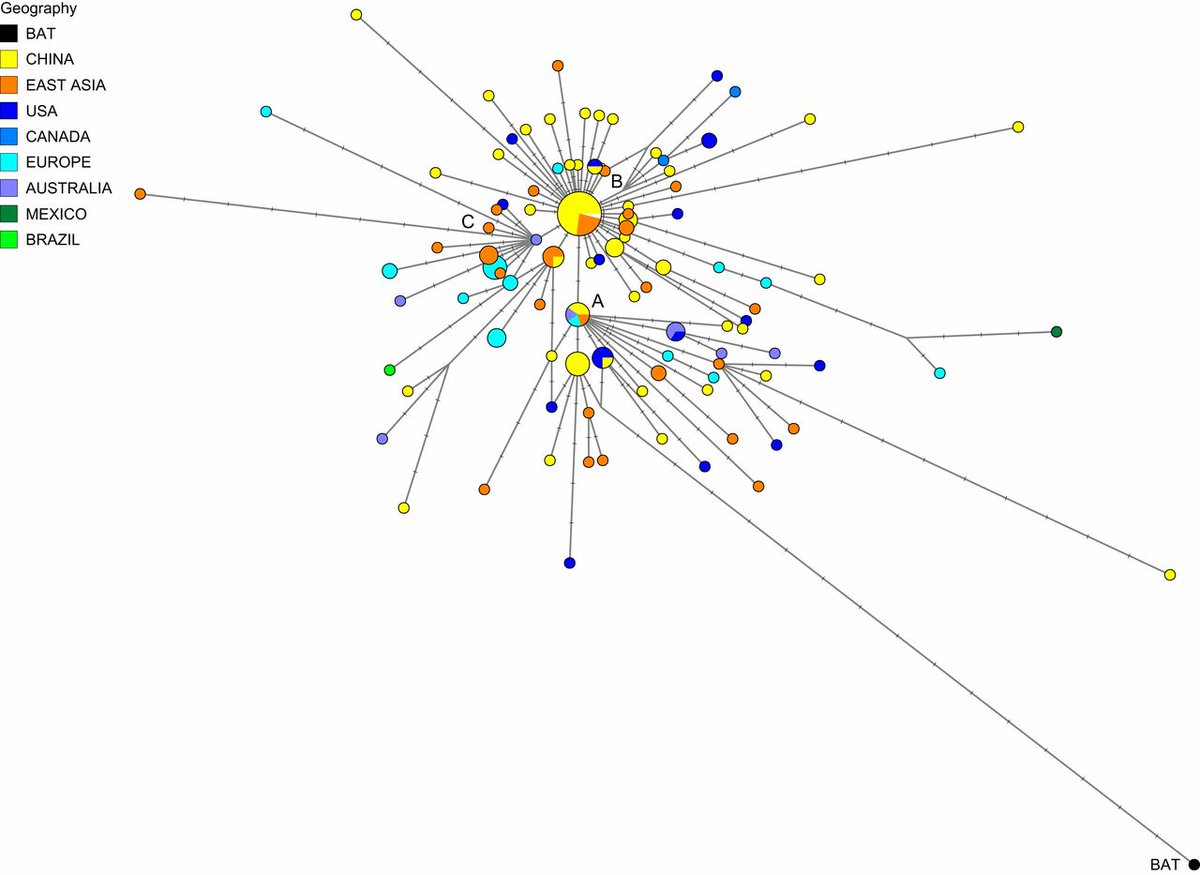

Scientists from UK and Germany attempted to genetically map the earliest strands of SARS-CoV-2 in order to create a picture of the virus' evolution. Estimates first infection between mid-Sep and early December. cam.ac.uk/research/news/…

This analysis from Harvard Medical School uses satellite imagery and Baidu search logs to infer the time of first infections at around mid-August or September 2019 dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/42669…

This Italian study indicates that antibodies to the virus may have been present as early as September 2019 journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/03…

University of Kent study using techniques from Conservation Science estimates the virus may have emerged around early October to mid-November. kent.ac.uk/news/science/2…

Study using social media mentions of keywords like "pneumonia" and "dry cough" to infer atypical patterns indicative of early COVID-19 ocurrence in Europe finds traces starting in mid-December nature.com/articles/s4159…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh