Today in pulp... a band of fearless rebels, a glowing sword, a mysterious 'force' and a masked baddie. Sounds familiar? Well the year is 1980, and the new decade has summoned a new movie hero. Sort of.

This is the epic saga of Hawk the Slayer!

This is the epic saga of Hawk the Slayer!

In the early 1980s there were a slew of B-movies cashing in on the Star Wars phenomenon, but it took cinema much longer to latch on to sword and sorcery. Hawk the Slayer was the low-budget British Film that spanned the gap.

In 1979 writer Terry Marcel and musician Harry Robertson (of Hammer horror and Lord Rockingham's XI fame) were working on adapting a Ray Cooney play when they got chatting about Fritz Lieber and fantasy novels.

Marcel had an idea for a fighting fantasy spaghetti western, and he and Robertson soon worked this up into a script. Chips Productions would fund it and ITC agreed to be the distributor. The budget? Only £600,000. Hardly a fistful...

Undeterred they set about casting the movie. Jack Palance was their big hire as the villainous disfigured Voltan, and he brought a manic energy to a role he probably didn't suit.

John Terry was chosen to play Voltan's brother Hawk - even though he was 30 years younger than Palace! He kept an unemotional face very still under his mullet throughout the film.

Told partly in flashback, Hawk the Slayer is a revenge story: Voltan kills his own father to try and gain control of the last of the magical mindstones.

His brother Hawk vows revenge...

His brother Hawk vows revenge...

Hawk is given the mindstone by his dying father, which fits in the hilt of his now-magical flying psychic sword. If this sounds like a steal from Michael Moorcock's Elric novels it's because it probably is.

Voltan goes on an evil rampage across the country, finally kidnapping nuns and demanding a huge ransom for their release. In deaperation the abbey turns to Hawk to save the day.

Hawk recruits a band of mercenaries including a not-tall giant (Bernard Bresslaw), a not-small dwarf (Peter O'Farrell) and an all-seeing blind witch called Woman (Patricia Quinn).

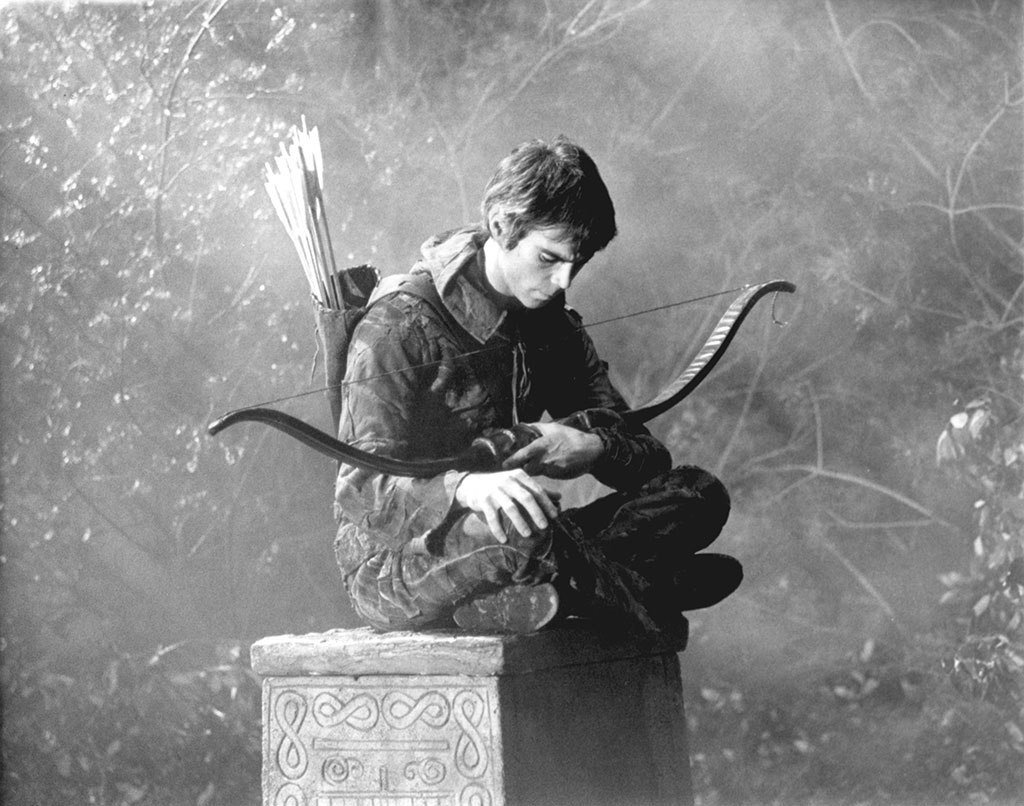

Firepower is provided by taciturn elf archer Crow (Ray Charleson) and crossbow fiend Ranulf (Morgan Sheppard). Between them they bring Peckinpah-level violence to the fight scenes. Of which there are many.

Location filming took place in Buckinghamshire, with painted mattes used for background buildings and dry ice liberally used for atmosphere. Studio work was done in Borehamwood.

Special effects were very low-cost: ping-pong balls were used for fire bolts, silly string acted as a mummify spell, there was even an indoor snow storm created with torn paper.

Robertson's score was equally bizarre: disco synth! But despite its critical panning, Hawk the Slayer is still held in affection by many as a film that stays close to its Dungeons and Dragons roots.

There's lots of spaghetti western touches too: close ups of twitching eyes and hands ready to draw. It's a fast-paced movie too, apart from the final Hawk / Voltan duel which is entirely in slo-mo.

A sequel has been in development hell since 1981. And despite rumours of a Hawk the Destroyer movie in 2015 (with Rick Wakeman providing the score) chances of a franchise emerging any time soon remain slim.

Hawk the Slayer is certainly a movie you should watch once, not least to spot how much it foreshadows the fantasy movies that come after it. It's good fun, and £600,000 well spent.

And NOT rubbish!

More stories another time...

And NOT rubbish!

More stories another time...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh