Time once again for my occasional series "Women with great hair fleeing gothic houses!"

There are a lot of these...

There are a lot of these...

What is gothic romance? Essentially it's about a relationship between a young woman and an old house. She may have inherited it, married into it or sought refuge in it. But slowly a sinister echo of the past is magnified by its walls, and in horror she must try and flee it.

Why flee a house? Why not a man, a cruel stepmother or a ghost? Well they can all play a part in gothic romance, but the locus of evil is usually the house itself. It's a genre based on a fear of engulfment - of being taken over, driven mad, suffocated by someone else's past.

In gothic romance there has to be a love story, but as in all tragedy there are three people in the relationship; the heroine, the brooding lover and the past. The past seeps through the landscape and the architecture - it is always malevolently watching.

At its peak in the early 1970s gothic romance was hugely popular, with several thousand novels written. But each had the same basic cover: a woman with great hair fleeing a gothic house. The was the acme of the story - the flight into terror as the past is finally revealed.

Why was gothic romance so popular? Well it touched on many themes an audience could relate to: extremes of passion, the sensual nature of the world, the occult. What the heroine wanted to possess - a lover, a marriage, an estate - might well destroy her as a person.

So in no particular order I'm going to share with you some of the many thousand gothic romances that were published in the '60s and '70s, and hopefully prove that it's a genre with both depth and merit.

The ur-text of modern gothic romance: Wuthering Heights, by Emily Brontë. Bantam Books, 1974 .Cover by Robert McGinnis.

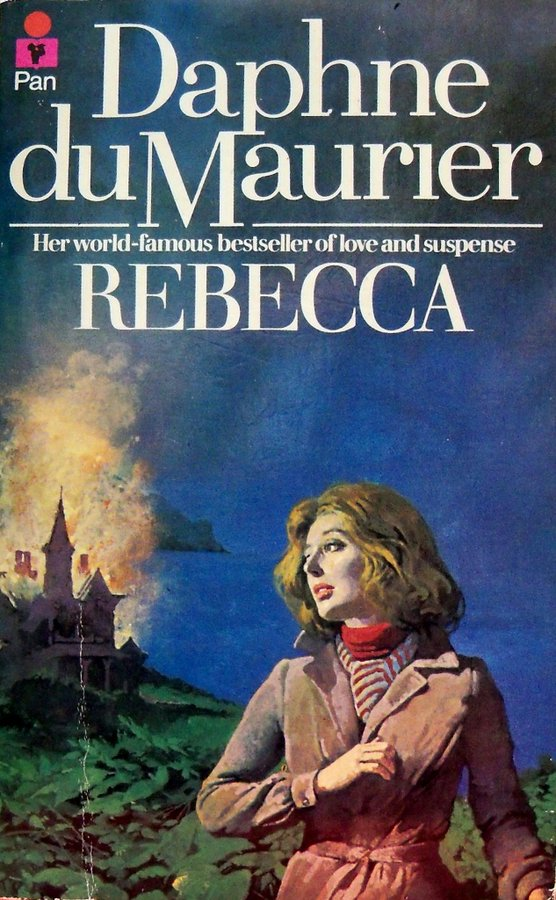

“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again…”

Rebecca, by Daphne Du Maurier. Pan Books, 1976. First published in 1938 it has never gone out of print. It paved the way for the post-war gothic romance revival.

Rebecca, by Daphne Du Maurier. Pan Books, 1976. First published in 1938 it has never gone out of print. It paved the way for the post-war gothic romance revival.

In 1960 Mistress of Mellyn, by unknown author Victoria Holt, became an overnight publishing success. Many believed du Maurier had written the book under a pseudonym. Actually it was penned by prolific British author Eleanor Hibbert.

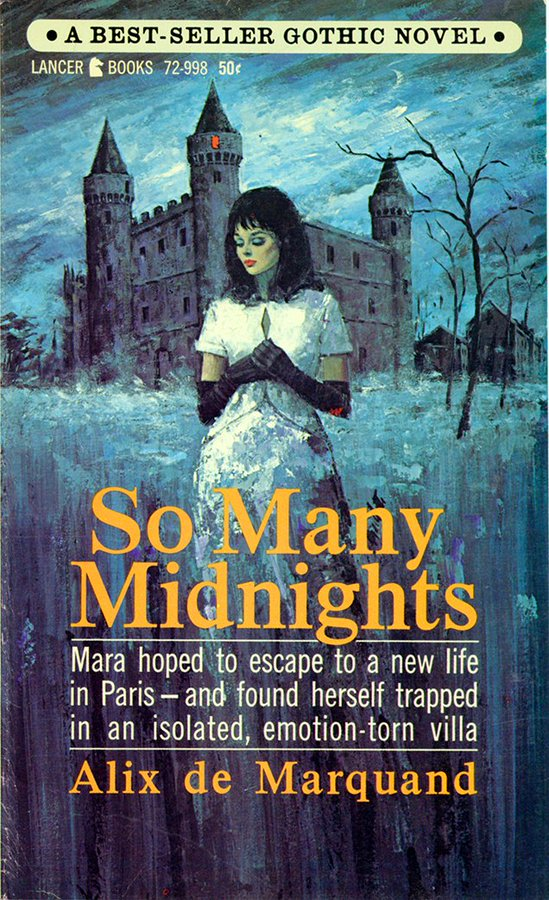

So Many Midnights, by Alix de Marquand. Lancer Books, 1966. Cover by Lou Marchetti. The heroine fighting for her inheritance in another country is a popular gothic romance theme.

Daughter Of Darkness, by Edwina Noone (aka Michael Avallone). Signet Books, 1966. Cover by Allan Kass. Many men wrote gothic romance novels, but publishers preferred them to have a female nom de plume.

The Brooding Lake (aka Lamb To The Slaughter), by Dorothy Eden. Ace Gothic, 1966. Eden wrote over 40 gothic romances between 1940 and 1982 and remains one of the best known names of the genre.

Hawthorne, by Ruth Wolff. Paperback Library Gothic, 1969. Cover by George Ziel. In the 1960s Ziel's style was instantly recognisable - long black dresses, bleak moorland and wind-tossed hair in the moonlight.

Hawk Over Hollyhedge Manor, by Dorothy Dowdell. Avon Gothic, 1973. Cover by Walter Popp. Another popular choice for gothic romance covers, Popp regularly used unusual angles and perspective to add dread to the artwork.

Dead By Now, by Margaret Erskine (aka Margaret Wetherby Williams). Ace Books, 1971. An unusual gothic romance / detective crossover series featuring Inspector Septimus Finch.

Lord Satan, by Louisa Bronte. Avon Satanic Gothic, 1972. Another crossover series where the satanic horror is cranked up along with the gothic romance. There's a number of titles to collect in this series.

Ancient Evil, by Candace Arkham (aka Alice Louise Ramirez). Popular Library, 1977. Many gothic romances were labelled 'Queen-Size', 'Easy Read' or 'Large Print' meaning they were in large font.

Gothic Tales Of Love (Marvel Comics, 1975) and The Sinister House Of Secret Love (DC Comics, 1972). Both Marvel and DC unsuccessfully tried to run gothic romance comics in the 1970s. Back issues can now cost you up to £200.

That's it for my look back at gothic romance novels today. I hope you enjoyed it.

More women with great hair fleeing gothic houses another day...

More women with great hair fleeing gothic houses another day...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh