“You’re running out of time.”

#NowWatching “Minority Report”

Apparently I’m on an accidental Steven Spielberg binge.

This is my first time rewatching this in decades. I last saw it as a teenager, and I didn’t love it.

I thought it was too cynical. I was so young.

#NowWatching “Minority Report”

Apparently I’m on an accidental Steven Spielberg binge.

This is my first time rewatching this in decades. I last saw it as a teenager, and I didn’t love it.

I thought it was too cynical. I was so young.

“Most of our scrambIes are fIash events. We rareIy see premeditation anymore.”

“PeopIe have gotten the message.”

“Uh-huh.”

It’s hard to believe, but “Minority Report” was written and shot before 9/11.

Which odd, because it feels like a quintessential War on Terror film.

“PeopIe have gotten the message.”

“Uh-huh.”

It’s hard to believe, but “Minority Report” was written and shot before 9/11.

Which odd, because it feels like a quintessential War on Terror film.

It’s a film about state overreach and the erosion of civil liberties in the name of a more secure and seemingly stable society.

Naturally, “Minority Report” suggests that there’s something very cynical and horrific lurking beneath the surface.

Naturally, “Minority Report” suggests that there’s something very cynical and horrific lurking beneath the surface.

Much is made in “Minority Report” of how there have been no reported murders since the system came into place.

However, there are recurring suggestions that something is deeply amiss. Washington D.C. still looks decayed. People are still missing. Organs are still traded.

However, there are recurring suggestions that something is deeply amiss. Washington D.C. still looks decayed. People are still missing. Organs are still traded.

“You're gonna beat everybody. I think you’ll beat everyone someday.”

The part of the War on Terror metaphor that resonates most particularly beyond the “liberty and security” stuff is the portrayal of this erosion of civil liberties as a direct response to trauma.

The part of the War on Terror metaphor that resonates most particularly beyond the “liberty and security” stuff is the portrayal of this erosion of civil liberties as a direct response to trauma.

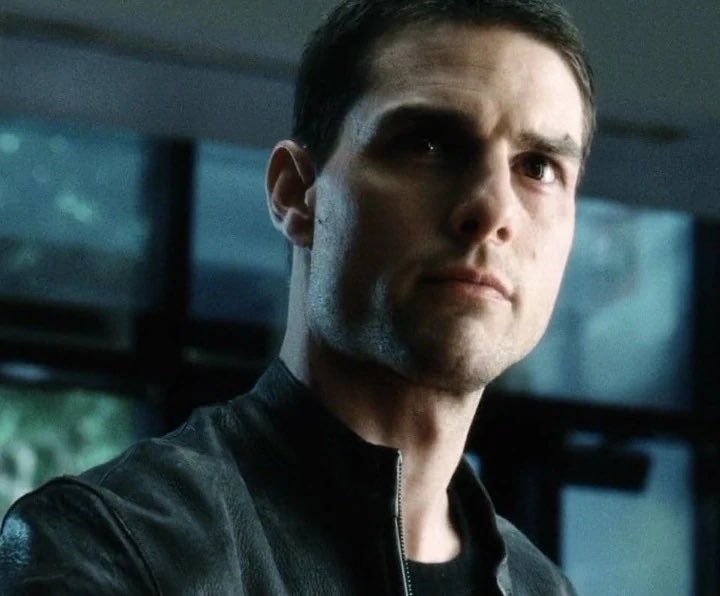

Anderton is motivated to preserve and defend pre-crime because he is nursing the trauma of the loss of his son.

He wants to prevent that from happening to anyone else, to believe that if pre-crime had existed, his son would still be safe.

He wants to prevent that from happening to anyone else, to believe that if pre-crime had existed, his son would still be safe.

It gives “Minority Report” a very strong sense of emotional stakes. Anderton doesn’t just enforce these violations of civil liberties, he believes in them. He doesn’t just believe in them, he needs to believe into them.

It feels very true to that cultural moment.

It feels very true to that cultural moment.

“In a week, peopIe wllI vote on whether or not what we've been doing has been a nobIe-minded enterprise or a chance to change the way this country fights crime.”

The plot of “Minority Report” also generates tension by positioning Anderton’s case so near the referendum.

The plot of “Minority Report” also generates tension by positioning Anderton’s case so near the referendum.

There’s a sense in which, much like Anderton needs to believe in what he does, everybody involved in this violation also needs to believe in what they’ve been doing.

Because if the public rejects pre-crime, it means what they’ve already done has been monstrous.

Because if the public rejects pre-crime, it means what they’ve already done has been monstrous.

Again, there’s this sense that these sorts of violations require buy-in and investment. Once a society begins doing these sorts of things, they get very good at rationalising it.

It becomes harder to accept that these things were mistakes, because that would compromise society.

It becomes harder to accept that these things were mistakes, because that would compromise society.

Again, it’s an aspect of the film that has aged rather well.

Think of how hard it has been to roll back the erosion of civil liberties during the War on Terror or to reverse the damage done during the Trump administration, because they would mean reckoning with those actions.

Think of how hard it has been to roll back the erosion of civil liberties during the War on Terror or to reverse the damage done during the Trump administration, because they would mean reckoning with those actions.

“Sit here a minute and listen to me. Your husband is being arrested

by Precrime.”

One of the shrewder aspects of “Minority Report” is how it opens by bringing the audience on board.

It shows the successfully prevention on a homicide, asking the audience to root for Anderton.

by Precrime.”

One of the shrewder aspects of “Minority Report” is how it opens by bringing the audience on board.

It shows the successfully prevention on a homicide, asking the audience to root for Anderton.

As with “A.I.”, there’s a sense of Spielberg weaponising all of the tricks of his trade against the audience.

Spielberg makes the opening sequence genuinely thrilling. He invites the audience to sympathise with the jackboot fascists, to enjoy a job well done.

Spielberg makes the opening sequence genuinely thrilling. He invites the audience to sympathise with the jackboot fascists, to enjoy a job well done.

Again, this is very much the logic of the cop shows that permeate American popular culture - and which enjoyed a crest at around this point thanks to the success of “CSI.”

Of course audiences wanted to believe that these people would keep us safe, no matter the cost.

Of course audiences wanted to believe that these people would keep us safe, no matter the cost.

There is perhaps something interesting in the way that this plays on movie-watching as a fundamentally passive experience.

The audience just sits there and experiences the story being told, without generating their own sounds or image, without stopping to process it.

The audience just sits there and experiences the story being told, without generating their own sounds or image, without stopping to process it.

There’s a passivity to movie-watching.

This is interesting in the context of “Minority Report”, a film about cops who themselves act with minimal agency based of footage they are shown.

That footage can be manipulated, edited, gamed, altered. It cannot be trusted.

This is interesting in the context of “Minority Report”, a film about cops who themselves act with minimal agency based of footage they are shown.

That footage can be manipulated, edited, gamed, altered. It cannot be trusted.

Indeed, like Nolan’s “Memento” from the previous year, the entire premise of “Minority Report” is rooted in movie characters who are victims of a manipulative and vindictive edit.

There’s something very clever in this, following on Spielberg’s self-awareness in “A.I.”

There’s something very clever in this, following on Spielberg’s self-awareness in “A.I.”

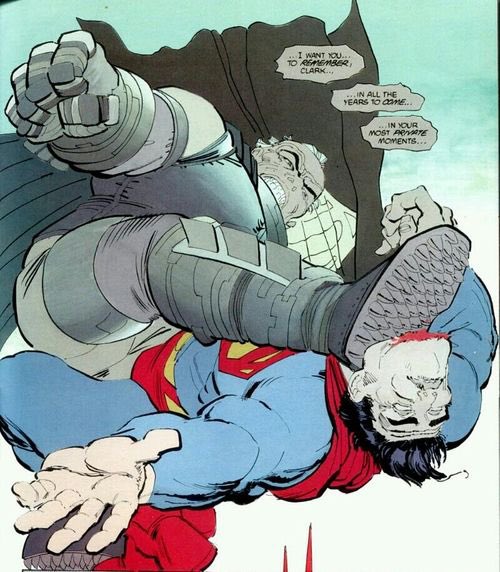

“Minority Report” is interesting because Spielberg understands the importance of imagery to fascism as an ideology.

This was the central thematic tension of “Raiders of the Lost Ark”, which is about using cinema to collapse the iconography of fascism.

This was the central thematic tension of “Raiders of the Lost Ark”, which is about using cinema to collapse the iconography of fascism.

Indeed, it’s notable that “Raiders of the Lost Ark” is another movie where audiences have actively questioned the agency of the main character in his own narrative.

But it’s ultimately about using film to explore how such movements built around hollow imagery crumble so easily.

But it’s ultimately about using film to explore how such movements built around hollow imagery crumble so easily.

This makes “Minority Report” an interesting companion piece to “Raiders of the Lost Ark”, which understands the dangerous allure of fascism as imagery absorbed passively.

But also the limitations of it when those images come up against something more powerful.

But also the limitations of it when those images come up against something more powerful.

“Can't Iet you take that out of here,

chief. It's against the rules.”

“Anything eIse here against the rules?”

And, naturally, “Minority Report” signals how broken the system is early on and consistently.

Much is made of Anderton acting on impulse and breaking the rules.

chief. It's against the rules.”

“Anything eIse here against the rules?”

And, naturally, “Minority Report” signals how broken the system is early on and consistently.

Much is made of Anderton acting on impulse and breaking the rules.

Anderton has a drug addiction. He takes data from the archives when shouldn’t.

He turns a blind eye to corruption, and the characters around him turn a blind eye to his own impropriety.

But Anderton is presented as the lead of a prestige show about a trouble cop.

He turns a blind eye to corruption, and the characters around him turn a blind eye to his own impropriety.

But Anderton is presented as the lead of a prestige show about a trouble cop.

The opening act of “Minority Report” very cleverly shows you how broken this world is, and how corrupt the system is.

However, it counts on the audience excusing it as just a genre convention, because this is just how cop shows work, right?

Anderton gets results.

However, it counts on the audience excusing it as just a genre convention, because this is just how cop shows work, right?

Anderton gets results.

“Minority Report” does a great job of showing its audience the problems with this system, while counting on their passive absorption of these sorts of narratives to excuse it.

Until it all explodes on Anderton and comes crumbling down around him.

Until it all explodes on Anderton and comes crumbling down around him.

Indeed, “Minority Report” arguably pulls something of a clever genre shift, beginning as a procedural cop show that assumes the audience is rooting for these violations.

It then swerved sharply into a neonoir about how the world is broken, all the more effective for that set-up.

It then swerved sharply into a neonoir about how the world is broken, all the more effective for that set-up.

“I find it interesting that some people

have begun to deify the Precogs.”

“Minority Report” feels like a meditation on religion, which makes it an interesting companion piece to “A.I.”

Spielberg is entering the elder statesman stage of his career, dealing with hefty themes.

have begun to deify the Precogs.”

“Minority Report” feels like a meditation on religion, which makes it an interesting companion piece to “A.I.”

Spielberg is entering the elder statesman stage of his career, dealing with hefty themes.

In “A.I.”, it was suggested that mankind constructed artificial intelligence to wrestle with its own questions about the divine - to make sense of the unknown.

If you want to get very Spielbergian on it, mankind wanted to grapple with the ultimate absent father.

If you want to get very Spielbergian on it, mankind wanted to grapple with the ultimate absent father.

In “Minority Report”, it is suggested the state has assumed religious authority, its decrees and mandates treated as religious proclamations.

Again, this arguably helped “Minority Report” age well as a War on Terror parable, given Bush and Blair’s use of faith-based language.

Again, this arguably helped “Minority Report” age well as a War on Terror parable, given Bush and Blair’s use of faith-based language.

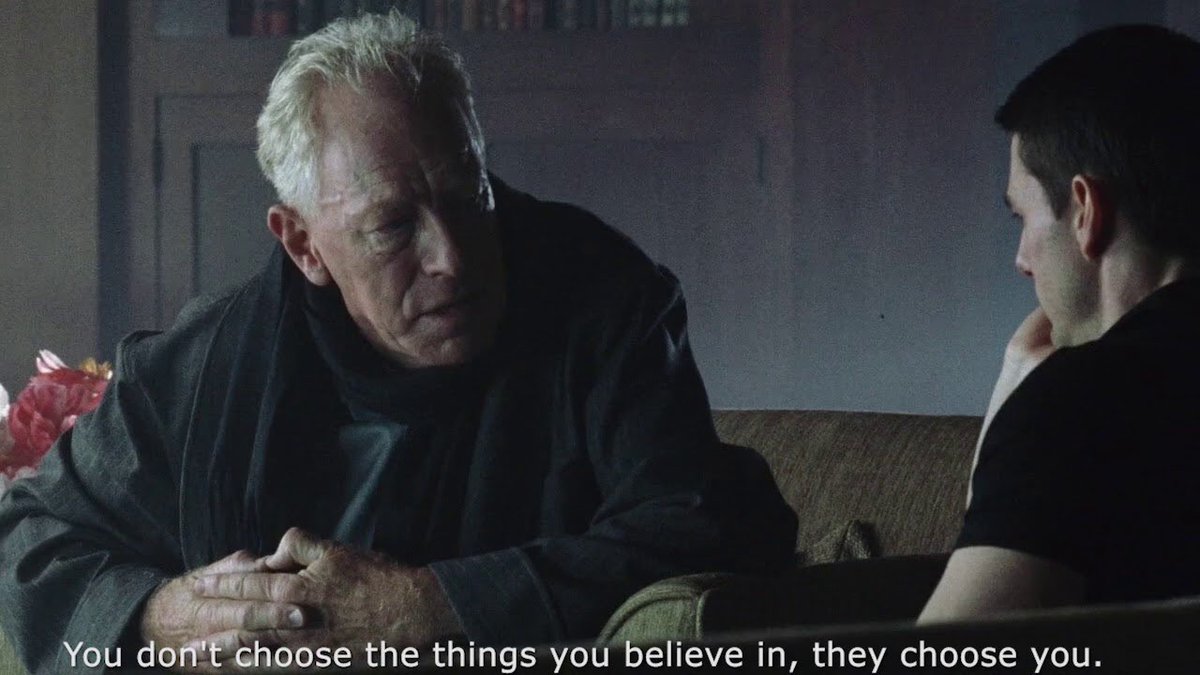

In this context, it’s notable that the only person to express actual doubts about pre-crime is Irish Catholic Danny Witwer.

Danny’s father was killed outside his local church. Danny wears a medallion that he kissed for good luck. Danny implicitly has actual faith.

Danny’s father was killed outside his local church. Danny wears a medallion that he kissed for good luck. Danny implicitly has actual faith.

At the core of “Minority Report” is the understanding that there is something horrific in a state that doesn’t just demand obedience from its citizens, but also demands their unwavering faith. Their blind faith, indeed.

There’s something horrific in that.

There’s something horrific in that.

“In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.”

Spielberg doesn’t tend towards subtlety, but even he hits the whole eyes thing pretty hard.

The opening killer forgets his glasses. Anderton’s drug dealer has no eyes. “The eyes (cough)… the eyes of the nation…”

Spielberg doesn’t tend towards subtlety, but even he hits the whole eyes thing pretty hard.

The opening killer forgets his glasses. Anderton’s drug dealer has no eyes. “The eyes (cough)… the eyes of the nation…”

It’s not a particularly subtle visual, thematic and narrative motif, but there’s something very clever in how “Minority Report” is a horror about the state watching its citizens rather than the citizens keeping their eyes on the state.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh