2/ First, the basics. The antifragile (a term coined by Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his homonymous book) is what benefits from variation, usage, problems, and feedback.

Example: using our muscles to lift weights makes them stronger.

Example: using our muscles to lift weights makes them stronger.

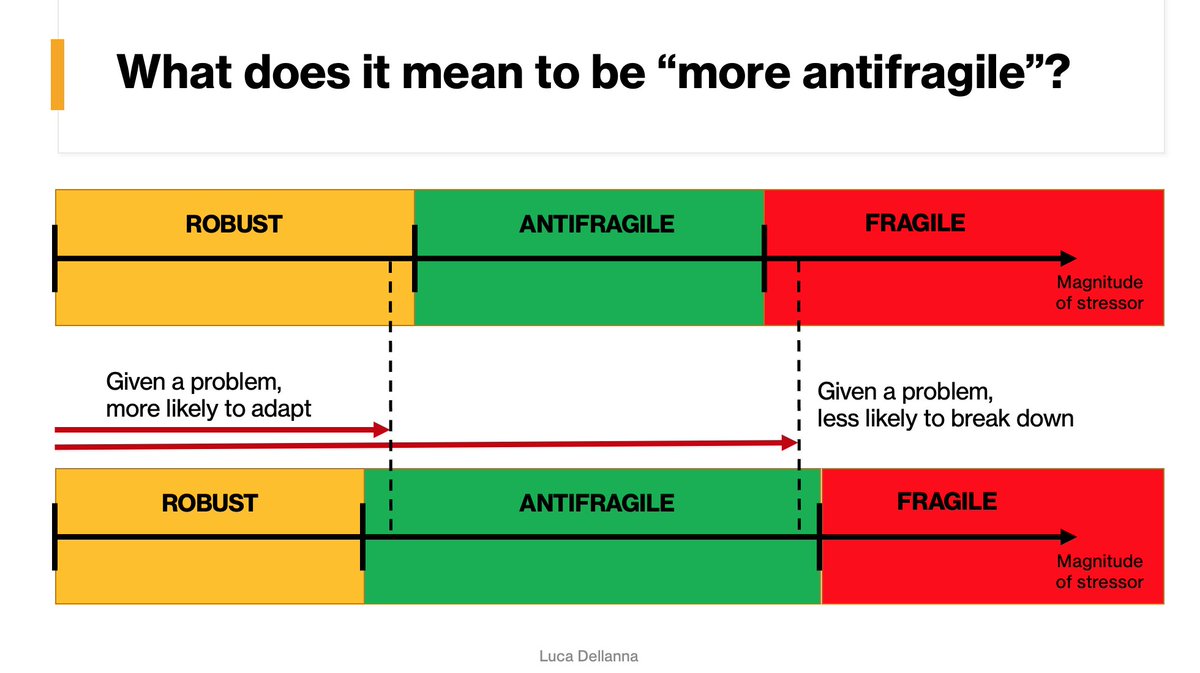

3/ The antifragile also exhibits robust and fragile behaviors.

(In the picture below, the former diagram represents the fragile and the latter represents the antifragile.)

(In the picture below, the former diagram represents the fragile and the latter represents the antifragile.)

4/ You can read the diagram as follows: the stronger a stressor (a hit, a problem…), the higher the chances that it will cause a fragile reaction (a breakdown).

The weaker the stressor, the higher the chances it won't cause a reaction.

(w/ some simplification, addressed below)

The weaker the stressor, the higher the chances it won't cause a reaction.

(w/ some simplification, addressed below)

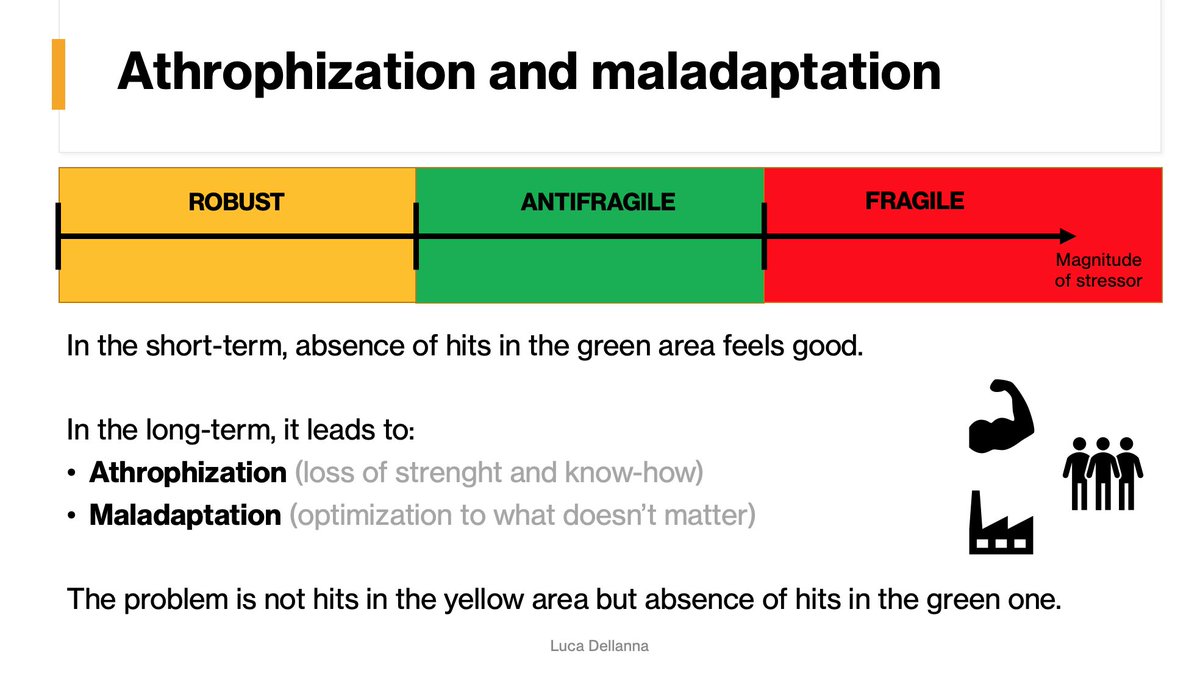

5/ Of course, being hit in the red area is bad (it can mean injury, death, bankruptcy, etc.).

And of course, being hit in the green area is good (it triggers an antifragile reaction that makes us stronger).

But what about being hit in the yellow area?

And of course, being hit in the green area is good (it triggers an antifragile reaction that makes us stronger).

But what about being hit in the yellow area?

6/ A hit in the yellow area causes no reaction. So it's not bad.

However, if the green area doesn't get hit at least once in a while, the system gets weaker.

Examples:

- no exercise for too long → muscles atrophy.

- no problems for too long → complacency.

However, if the green area doesn't get hit at least once in a while, the system gets weaker.

Examples:

- no exercise for too long → muscles atrophy.

- no problems for too long → complacency.

8/ If the green area doesn't get hit for too long, it shrinks.

As a result, a stressor that used to cause an antifragile reaction now causes a fragile one (in the case of the couple of red arrows to the right) or a robust one (in the case of the left one).

As a result, a stressor that used to cause an antifragile reaction now causes a fragile one (in the case of the couple of red arrows to the right) or a robust one (in the case of the left one).

9/ Long story short: if the antifragile doesn't receives stressors that cause an antifragile reaction for too long,

- it becomes more likely to break down, and

- it becomes less likely to adapt

- it becomes more likely to break down, and

- it becomes less likely to adapt

10/ (I made a *huge* simplification in the movement of the left threshold in the previous set of diagrams: it might move left for some layers of the system and right in others. I plan to produce another video soon to explain this complex point. Still, the previous point holds.)

11/ Is having a large yellow area good or bad?

Early on, it feels good: less pain & disruption

However, you become less likely to adapt & thus out of sync with your environment

That's bad: in the short term, adaptation doesn't matter; but in the long one, it's all that matters

Early on, it feels good: less pain & disruption

However, you become less likely to adapt & thus out of sync with your environment

That's bad: in the short term, adaptation doesn't matter; but in the long one, it's all that matters

12/ Now that I covered the basics, let's see how this visual framework can be useful.

First of all, it clearly shows the relationship between stressor, damage, and reaction.

It's important, because…

(continues below)

First of all, it clearly shows the relationship between stressor, damage, and reaction.

It's important, because…

(continues below)

13/ It allows you to turn questions around, from the generic "how do I become more antifragile" to a more actionable "how do I become less likely to be broken and more likely to adapt?"

And it makes it more visual.

And it makes it more visual.

14/ The diagram provides an easy way to interpret what it means to be "more antifragile":

- you are more likely to adapt to what you wouldn't have adapted before

- you are less likely to be broken by what would have broken you before

(some limitations in the thread)

- you are more likely to adapt to what you wouldn't have adapted before

- you are less likely to be broken by what would have broken you before

(some limitations in the thread)

15/ You can split the diagram in two halves: adaptation and survival.

Though they are not independent: to adapt, you must survive; and the more you adapt (to the right thing), the more likely you are to survive. I explore this dependence elsewhere.

Though they are not independent: to adapt, you must survive; and the more you adapt (to the right thing), the more likely you are to survive. I explore this dependence elsewhere.

18/ …and a summary.

(There are limitations, e.g. the diagram doesn't consider the possibility to change the exposure to stressors, which is an extremely important lever to both survival and adaptation. Here, I focus on changes within the entity represented by the diagram)

(There are limitations, e.g. the diagram doesn't consider the possibility to change the exposure to stressors, which is an extremely important lever to both survival and adaptation. Here, I focus on changes within the entity represented by the diagram)

19/ More on the limitations.

In this thread, I'm making a lot of simplifications for the purpose of facilitating the introduction to a complex topic.

In this thread, I'm making a lot of simplifications for the purpose of facilitating the introduction to a complex topic.

20/ I talk in more practical terms about antifragility in my cohort-based course, which focuses less on the what and more on the how, in particular from the point of view of organizations: maven.com/luca/antifragi…

21/ Here is a video that illustrates the framework.

I will publish more videos over the next days in my newsletter (luca-dellanna.com/newsletter)

I will publish more videos over the next days in my newsletter (luca-dellanna.com/newsletter)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh