Is the market a bubble ready to burst? In this thread, we'll consider what share buybacks have to say about it: (THREAD)

With dividends being relatively stable and the DCF placing a lot of weight on the terminal value (long-term growth after 5 years), the main variable to consider is the pace of share buybacks, which affect the payout ratio. /2

Historically, earnings growth has been 6% in the US, and in recent years the payout ratio has been around 90%. Currently (a/o Q1) it’s 71%, with dividends comprising 35% and buybacks 36%. /3

The pandemic put an abrupt halt to buybacks last year and that has taken down the payout ratio 20 points. Since buybacks tend to follow earnings growth, the payout ratio will typically lag into an earnings recovery. /4

Even at 71%, US companies still buy back more shares than companies in Europe and Japan (where the payout ratios are closer to 50%). This may be one reason why US equities tend to have higher valuations, and have outperformed non-US equities in recent years. /5

The grid below shows that, at a 6% annual growth rate for earnings, a 10-percentage point shift in the payout ratio corresponds to a six-point shift in the P/E ratio. /6

With dividends being relatively stable, share buybacks are the swing factor that drive changes in the payout ratio, which in turn affects the P/E multiple. The question, at least for this exercise, is whether buybacks are a product of easy money policies. /7

There is no easy answer to that question. While it seems intuitive to conclude that the Fed’s easy money policy has led to financial arbitrage (borrowing cheaply to buy back shares) and capital misallocation, I’m not prepared to draw that conclusion. /8

It’s my sense that most buybacks are the result of profitable companies producing excess cash flows, even after CAPEX, and wanting to return that idle cash to shareholders. Think of it as a modern-day dividend. /9

This chart shows how remarkably stable the pace of free cash flows (FCF) has been as a percent of sales. Since the recovery of the financial crisis, for the S&P 500 index that number has been around 10%, while CAPEX has been around 6% and dividends of 4%. /10

If the Fed was blowing bubbles and creating a cash flow illusion for stocks, or somehow was incentivizing companies to misallocate capital by buying back shares rather than investing in CAPEX, I would expect that chart to look different. /11

That's not to say there isn’t financial arbitrage going on. This chart shows annual borrowing by non-financial corporates as well as the annual flow of buybacks, acquisitions and equity issuance (all from the Fed’s Flow-of-Funds report). /12

So there is plenty of financial arbitrage going on. But it's not clear whether this is the direct result of monetary policy. There was a buyback boom from 2004-07, but that was before the QE/ZIRP era. The Fed was even raising rates during the latter part of that period. /13

This next chart shows that the buyback era began in the mid-2000s. From the 1980s to the 2000s, the equity float (and therefore the S&P 500 divisor) was generally rising, but it peaked in 2004 and has been declining ever since. /14

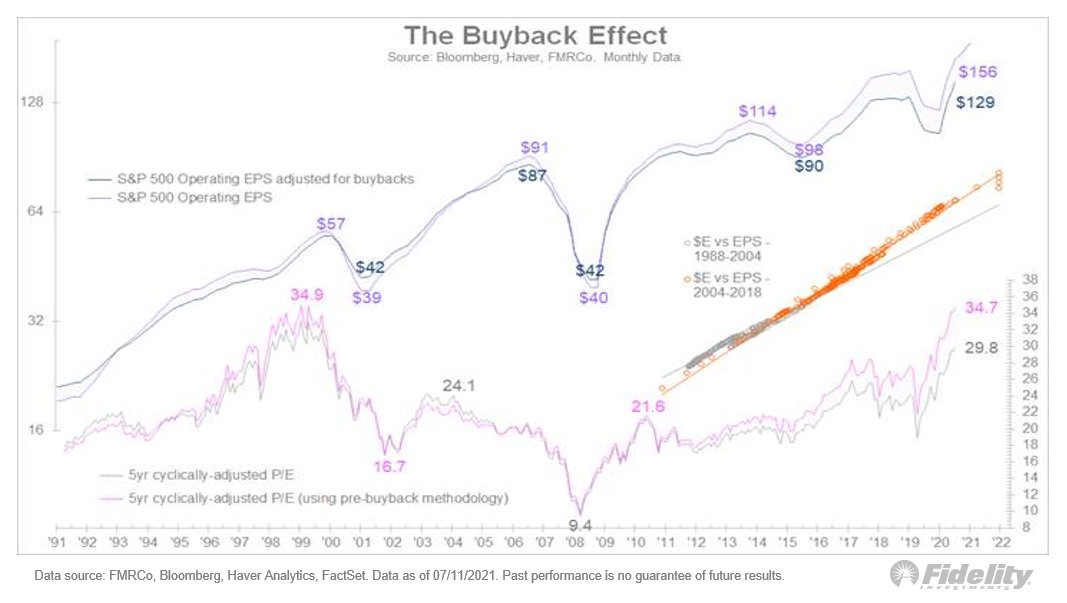

Regardless of motivation, buybacks impact the market in two ways. First, they inflate the market’s earnings per share, and therefore understate the P/E ratio, by reducing shares outstanding. Same earnings but lower shares = inflated EPS. /15

A simple way to demonstrate this is to regress EPS against the $ amount of earnings (both of which are published by S&P). If we do this for the pre-2004 period as well as the post-2004 period, we can see that the slopes are different (see scatter plot below). /16

The orange line above shows that every dollar of earnings produces more EPS than it used to (i.e. a steeper slope). To test what today’s EPS would be based on fewer buybacks, we can simply apply the old slope to today’s dollar earnings, below. /17

This increased “divisor leverage” has led to a 20% EPS inflation. This has, in turn, led to the P/E being understated. The current trailing P/E multiple (5yr CAPE) is 29.8x, but using the old slope it would be 5 points higher at 34.7x. /18

So what about the payout ratio? If companies in the S&P 500 only paid dividends, the current payout ratio would be 35%. That would warrant a lower valuation than the current 71% when buybacks are included. /19

We can see the impact in this chart: It shows the pre-Covid earnings path compared with the current consensus estimates (from Bloomberg). /20

As the DCF model on the right hand side of the chart shows, at a discount rate of 5.5% the difference between the current 71% payout and a 60% payout is roughly 600 SPX points, or 15%. /END

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh