Are the Pinkertons already out of the Discourse cycle, or would people be interested in an impromptu thread about them, private detecting in the 1850s, and where the myth of the romantic lone wolf private detective came from?

Okay.

Modern policing in the US sprang out of county sheriffs (NE US) & slave patrols (SE US). By the 1780s there were both federal law enforcement agencies (US Marshals) & urban police (Philly). In the UK, the 1st police agency was for policing the docks of London in the 1790s

Modern policing in the US sprang out of county sheriffs (NE US) & slave patrols (SE US). By the 1780s there were both federal law enforcement agencies (US Marshals) & urban police (Philly). In the UK, the 1st police agency was for policing the docks of London in the 1790s

But police as we know them today weren't around, because France had done that during the Revolution, and everyone hated the idea of bringing a French innovation into the UK & US--too easily an instrument for government abuse & oppression.

2/

2/

Plus popular sentiment in both England & its American colonies (later the USA) was *strongly* against the concept of the police. Both countries had a tradition of rooting for outlaw heroes and despising thief-takers.

So police departments were slow to form in both countries.

3/

So police departments were slow to form in both countries.

3/

So what happened around the turn of the 19th century is that "private enquiry agents" began forming, individually and in agencies. They advertised in newspapers & magazines but mainly got their money from thief-taking for companies and stolen goods retrieval for the wealthy.

4/

4/

From the very beginning, private detectives were most often tools of the powerful, using the law to oppress, harass, & abuse the powerless. Stolen goods retrieval meant beating people up until they talked; the tactics for thief-taking were even more brutal.

5/

5/

The London Bow Street Runners, a kind-of police force, had been around since 1749 & only disbanded in 1839--but everybody hated them, esp. because Runners were on a cheap stipend and depended on closing cases for rewards. This led to horrible abuses--anything to close a case. 6/

For the first half of the 19th century, there were some urban police departments and a lot more private detectives. Both hated. But, interestingly, private detectives and "police private detectives" (freelancers hired by the urban police) were lauded in fiction--cops were not. 7/

Detective fiction began in the 1810s and 1820s (yes, preceding Poe by two decades) in newspapers and magazines, and by a ludicrous margin (something like 9:1 IIRC) the heroes of those stories were either private 'tecs or police private detectives. 8/

By the 1830s detective fiction was a recognizable genre--coherent and separate from mainstream fiction. Reasons for this were the escalation in number of serials of fiction for the working classes, increase in published testimony of the police during trials, and a rise in

9/

9/

autobiographies of working class men and women as well as in true crime magazines (which avoided the stamp duty on newspapers by virtue of being differently sized).

Foresighted writers rushed to combine these things into detective fiction, which sold (and sold and sold).

10/

Foresighted writers rushed to combine these things into detective fiction, which sold (and sold and sold).

10/

(Poe really wasn't a founder of detective genre--he was a popularizer more than anything).

(If you're curious about these pre-Poe detective stories, check out the Westminster Detective Library: wdl.mcdaniel.edu)

(If you're curious about these pre-Poe detective stories, check out the Westminster Detective Library: wdl.mcdaniel.edu)

Jumping forward to 1849--in the UK, in the pages of the very well respected Chambers' Edinburgh Journal, there appeared a series of stories claiming to be written by ex-cop "Thomas Waters." (Actual author was William Russell, about whom little is known).

These stories claimed to be Waters' factual accounts of his life on patrol. The stories were the first in the police memoirs subgenre, and were all about hardboiled police work in the poor parts of London. Waters wrote for the middle class, so he soft-pedalled a lot of stuff. /13

The author made Waters seem to be a realistic, believable street cop, albeit one who used the newest scientific advances (i.e., examining blood and hair under a microscope) to solve crimes.

The Waters stories were about murder, broken families, and ruined finances.

/14

The Waters stories were about murder, broken families, and ruined finances.

/14

These were all *middle-class* concerns, not working-class concerns, & while Waters deserves credit for being the first hardboiled writer he was writing for the middle class. Waters' focus was on crime & the middle class, & the middle-class couldn't get enough of his stories.

/15

/15

Waters, in fact, was so popular that his crime stories can be seen as a prediction of and influence on the sensation novels of the 1850s & 1860s. #Victorianfiction

Waters' stories were massively popular, and the first collection of them, in 1856, was a bestseller.

/16

Waters' stories were massively popular, and the first collection of them, in 1856, was a bestseller.

/16

Meanwhile, as the Waters stories were hitting the stands in the magazines (1849-1853), Allan Pinkerton was forming his detective agency. Pinkerton liked to romanticize what he & his agents did during the early years, to match what fictional detectives (and Waters) said they did.

Here's what the Pinkertons REALLY did during the 1850s:

- "special" security and investigations for banks and railroads. "Special" because ordinary cops wouldn't do what Pinkerton & his agents did, which was to outrageously brutalize any suspects until they confessed.

/18

- "special" security and investigations for banks and railroads. "Special" because ordinary cops wouldn't do what Pinkerton & his agents did, which was to outrageously brutalize any suspects until they confessed.

/18

CW: sexual assault

Torture, rape, and mutilation were all a part of the Pinkertons' tactics in the 1850s. Banks and railroads--basically, anyone in power then--hated workers who didn't know their place, anarchists, and criminals with a toxic religious fervor. So--

/19

Torture, rape, and mutilation were all a part of the Pinkertons' tactics in the 1850s. Banks and railroads--basically, anyone in power then--hated workers who didn't know their place, anarchists, and criminals with a toxic religious fervor. So--

/19

bank and railway executives not only approved of the most brutal tactics imaginable against rebellious workers, anarchists, and supposed criminals, they preferred the Pinkertons engage in that behavior, pour discourager les autres.

The Pinkertons were happy to go along.

/20

The Pinkertons were happy to go along.

/20

The Pinkerton agents weren't merely good honest working men (and Kate Warne). They were chosen by Pinkerton for their physical abilities and willingness to do anything in order to close a case. Don't feel sympathy for them--they were torturers, violators, and murderers.

/21

/21

Kate Warne willingly went to work with them. She's no hero. Her colleagues were part of the war on the working class--on the wrong side.

What else did the Pinkertons do in the 1850s?

They tracked down counterfeiters, embezzlers, and "protected company property."

What else did the Pinkertons do in the 1850s?

They tracked down counterfeiters, embezzlers, and "protected company property."

Some of their targets were actually guilty. But a far larger percentage were only guilty because they confessed under duress after being savaged and abused, and because criminal judges hated workers like Inquisitors hated unbelievers.

/23

/23

This is why the "fruit of the poisoned tree" cliche in criminal law is a bitter thing to read. The entire damned tree of policing is poisoned and always has been.

Meanwhile, over in England, competitors to Waters began appearing--but not in newspapers or magazines.

/24

Meanwhile, over in England, competitors to Waters began appearing--but not in newspapers or magazines.

/24

Waters' competitors appeared in softcover story collections, with names like "Recollections of a Detective" and "Revelations of a Detective." These softcover collections came to be known as "casebooks." And the casebooks, whose heyday was ~1856 to ~1871, sold enormously.

/25

/25

(There was a RECOLLECTIONS OF AN INDIAN DETECTIVE published in Kolkata in 1885 that I'd love to read, even tho' I know it would simply be copaganda for the Raj. The "Indian" detective is an Anglo-India--"Superintendent, Calcutta Detective Dept." But...I wanna read it anyhow). /26

Waters wrote the first casebook detective stories, & in doing so created hardboiled detective fiction. But the post-Waters authors were the ones that made hardboiled a hugely popular genre. They did so by writing for the lower class, not the middle class, and by not holding back.

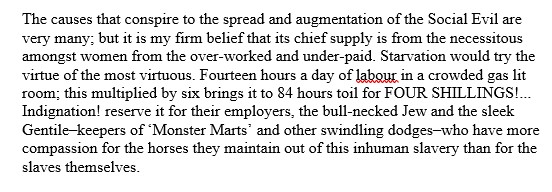

The casebook detectives were cynical and hardened by working the poor streets of London/Manchester/Glasgow. They saw the worst of Victorian England, and wrote about it, honestly. So they talked about prostitution & child prostitution. Abusive husbands. Seducers and their victims.

Most of all--and this must have been shocking to the middle class Victorians who read the casebooks--the casebook detectives tied poverty to crime in blunt, memorable ways. This unfortunately led to some anti-Semitism--the poor often only got money from Jewish moneylenders. But--

the casebook detectives, despite some anti-Semitic moments, were almost entirely sympathetic to POC, and most especially WOC. The detectives were all about the poor, and hated the middle classes for what they did to and allowed to happen to the poor.

The casebooks were actually quite revolutionary, and I remain shocked that they were a) allowed to see print and b) as ginormously popular as they were.

Let me see if I can pull up a quote.

Let me see if I can pull up a quote.

The Victorians really hated prostitution, of course, but they did nothing--and worse than nothing--to prevent its causes from taking place. The casebooks hated prostitution--street prostitution--because of what it did to the women they saw. Quoting from "Tom Fox:"

Detective fiction from the start had been all about romanticizing the detective. Casebook fiction did that--but the casebooks have a pronounced strain of real outrage in them that tells me they weren't just meant as "improving literature," they were meant as a slap in the face.

The casebooks were, as mentioned, very, very popular. Popular enough for pirated editions to appear in the US and become bestsellers in the 1860s.

Which is when the dime novel began developing, and guess what a very popular genre of dime novel story was? The detective story.

Which is when the dime novel began developing, and guess what a very popular genre of dime novel story was? The detective story.

As the dime novel detective stories appeared, the authors' names on those dime novels were, surprisingly often, taken from the casebooks--"Thomas Waters" and "Tom Fox" were popular dime novel pseudonyms.

But the dime novel authors never shared the casebook authors' outrage.

But the dime novel authors never shared the casebook authors' outrage.

Why? In part because American authors simply gave less of a fuck than British authors did--dime novel detective authors had no experience in the street the way casebook authors did. But also because in the 1860s and 1870s postal censorship was more intrusive in the US than the UK

You know where I'm going with this. Our old friend Anthony Comstock and his cronies tended to censor the living hell out of popular literature, like the dime novels. No dime novel would ever have been allowed to talk about child prostitution the way the casebooks did.

So the dime novel detective authors took character & author names from the casebooks as well as a sugar-coated form of hardboiledness, but left out the true part.

Nonetheless, the dime novels sold very well. As the casebooks before them had.

Nonetheless, the dime novels sold very well. As the casebooks before them had.

For most of the second half of the 19th century, the dime novels & casebooks were the most popular form of detective fiction.

So in the 1860s, when Allan Pinkerton begins publishing books about the Pinkerton Agency, he imitates the dime novel approach to detectives.

So in the 1860s, when Allan Pinkerton begins publishing books about the Pinkerton Agency, he imitates the dime novel approach to detectives.

What readers (American & English/European--Pinkerton's books sold widely) got was a valorization of & adulation of detectives. Pinkerton borrowed the dime novel hardboiled detective--popular with readers--and claimed his detectives were just like that, only totally real you guys!

And that's where the cultural archetype of the hardboiled detective came from. The interplay between Pinkerton, the dime novels, and the casebooks.

Just as dime novel writers stole casebook writers' names, so too did early pulp writers steal dime novel writers' names.

Just as dime novel writers stole casebook writers' names, so too did early pulp writers steal dime novel writers' names.

And that's where the American love of the Pinkertons came from: carefully-crafted p.r. campaigns. Pinkerton died in 1884 (and has been burning in Hell ever since), long after the Pinkertons turned their attentions to union- and strike-busting. He's no hero.

Nor were his vaunted efforts on behalf of the Union during the Civil War much to speak of. When McLellan was replaced as commander, Pinkerton quit working for the Union Army and took all his intelligence files with him. What war work he did after 1862 was desultory.

As for Kate Warne saving Lincoln...are you really going to believe that? The author of INVENTING THE PINKERTONS doesn't, and supports the idea that the supposed plot against Lincoln mostly existed in Pinkerton's head.

It's a very American thing to buy into the Pinkerton hype. We don't know our own history, we hate uppity workers, and we're suckers for lone wolf types. Always have. But I'm here to tell you, don't fall for it. The Pinkertons were villains, not heroes.

/Fin.

/Fin.

(The Sylvia Plath lines about "every women adores a fascist, the boot in the face, the brute" are more accurately applied to the US as a whole, I think). /Finforreal

Also--last tweet in this, I swear--at @readercon tomorrow I'm talking about Vikings and am also paneling on revamping the Western. See you there?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh