1/🧵

I like to think investment topics that on surface seem mundane but with deeper thought, are more complex than meets the eye.

One of such topics is INSURANCE FLOAT. This thread covers the basics of float and how to think about valuing it.

Best enjoyed with a cup of tea 🫖

I like to think investment topics that on surface seem mundane but with deeper thought, are more complex than meets the eye.

One of such topics is INSURANCE FLOAT. This thread covers the basics of float and how to think about valuing it.

Best enjoyed with a cup of tea 🫖

2/🧵

Let’s start with the basics.

If you’ve bought an insurance, you’ve paid an upfront fee called the “premium”. It is uncertain whether you will get anything back in form of “claims” over time, but the upfront fee must be paid, nevertheless.

Let’s start with the basics.

If you’ve bought an insurance, you’ve paid an upfront fee called the “premium”. It is uncertain whether you will get anything back in form of “claims” over time, but the upfront fee must be paid, nevertheless.

3/🧵

Insurance company holds the capital for the time between collecting premiums and paying out claims. This pool of funds is called the “float”.

In other words, float is money being held and invested by the insurance company but not owned by it.

berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2002pd…

Insurance company holds the capital for the time between collecting premiums and paying out claims. This pool of funds is called the “float”.

In other words, float is money being held and invested by the insurance company but not owned by it.

berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2002pd…

4/🧵

For the accounting fans out there, here’s the “scientific definition” used by Berkshire Hathaway.

Luckily, some insurance companies do disclose the aggregate numbers on a silver platter so you may put down your calculators.

For the accounting fans out there, here’s the “scientific definition” used by Berkshire Hathaway.

Luckily, some insurance companies do disclose the aggregate numbers on a silver platter so you may put down your calculators.

5/🧵

With regards to float, there are three critical considerations:

i) the cost of float

ii) the growth of float

iii) investment returns with float

Let’s look at each one.

With regards to float, there are three critical considerations:

i) the cost of float

ii) the growth of float

iii) investment returns with float

Let’s look at each one.

6/🧵

i) the cost of float

Float doesn’t come without commitments – there are future claims to be paid.

If insurer has underpriced risks, it suffers “underwriting losses” as claims exceed premiums over time. On the contrary, well-run insurers benefit from “underwriting profits”.

i) the cost of float

Float doesn’t come without commitments – there are future claims to be paid.

If insurer has underpriced risks, it suffers “underwriting losses” as claims exceed premiums over time. On the contrary, well-run insurers benefit from “underwriting profits”.

7/🧵

i) the cost of float

If insurance company is consistently posting underwriting profits, it is effectively BEING PAID to hold float, i.e. borrowing money at a negative interest rate.

Underwriting losses equal a cost (an interest paid) for the float.

i) the cost of float

If insurance company is consistently posting underwriting profits, it is effectively BEING PAID to hold float, i.e. borrowing money at a negative interest rate.

Underwriting losses equal a cost (an interest paid) for the float.

8/🧵

i) the cost of float

Take $BRK Berkshire Hathaway. Its stellar insurance operations have meant that most of the time it has held substantial float at an interest less than that of Treasuries.

Talk about investment tailwind.

arena-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/866910/37bb0e4…

fool.com/investing/2018…

i) the cost of float

Take $BRK Berkshire Hathaway. Its stellar insurance operations have meant that most of the time it has held substantial float at an interest less than that of Treasuries.

Talk about investment tailwind.

arena-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/866910/37bb0e4…

fool.com/investing/2018…

9/🧵

i) the cost of float

Here’s Warren Buffett emphasizing the low cost of float in 2002 and 2003 annual shareholder meetings.

Consequences of losing discipline with regards to the cost of float can be fatal, even for a large company.

buffett.cnbc.com/video/2003/05/…

i) the cost of float

Here’s Warren Buffett emphasizing the low cost of float in 2002 and 2003 annual shareholder meetings.

Consequences of losing discipline with regards to the cost of float can be fatal, even for a large company.

buffett.cnbc.com/video/2003/05/…

10/🧵

ii) the growth of float

We’ve now concluded that float can have either positive or negative cost, depending on the quality of the underlying insurance operations.

As float is the result of a “living organism” of a company, it can also grow over the years once it’s bought.

ii) the growth of float

We’ve now concluded that float can have either positive or negative cost, depending on the quality of the underlying insurance operations.

As float is the result of a “living organism” of a company, it can also grow over the years once it’s bought.

11/🧵

ii) the growth of float

Take again Berkshire Hathaway that started its insurance operations in 1967 by acquiring National Indemnity. More details of the deal in the following tweet.

ii) the growth of float

Take again Berkshire Hathaway that started its insurance operations in 1967 by acquiring National Indemnity. More details of the deal in the following tweet.

https://twitter.com/hkeskiva/status/1423882228111642627?s=20

12/🧵

ii) the growth of float

Between 1967 and 1996, Berkshire has grown its float at a staggering annual compounded rate of 22.3%.

berkshirehathaway.com/letters/1996.h…

ii) the growth of float

Between 1967 and 1996, Berkshire has grown its float at a staggering annual compounded rate of 22.3%.

berkshirehathaway.com/letters/1996.h…

13/🧵

ii) the growth of float

In 2Q2021, Berkshire’s float reached $142 billion for a 1967-2021 CAGR of 18.2%.

Such levels cannot be sustained as indicated by Mr. Buffett himself already in 2003 annual meeting.

buffett.cnbc.com/video/2003/05/…

ii) the growth of float

In 2Q2021, Berkshire’s float reached $142 billion for a 1967-2021 CAGR of 18.2%.

Such levels cannot be sustained as indicated by Mr. Buffett himself already in 2003 annual meeting.

buffett.cnbc.com/video/2003/05/…

14/🧵

ii) the growth of float

However, one of the largest U.S. auto insurers, Progressive $PGR, achieved similar 18.3% CAGR in 1991-2021.

Despite world-class examples, better not model such growth rates especially for greater base numbers (easier to grow when you’re small).

ii) the growth of float

However, one of the largest U.S. auto insurers, Progressive $PGR, achieved similar 18.3% CAGR in 1991-2021.

Despite world-class examples, better not model such growth rates especially for greater base numbers (easier to grow when you’re small).

15/🧵

ii) the growth of float

Obviously, no company can grow float faster than global GDP into perpetuity (otherwise float would eventually exceed GDP and that’s just dumb).

For some time, of course, float can grow faster than the industry capturing market share from rivals.

ii) the growth of float

Obviously, no company can grow float faster than global GDP into perpetuity (otherwise float would eventually exceed GDP and that’s just dumb).

For some time, of course, float can grow faster than the industry capturing market share from rivals.

16/🧵

ii) the growth of float

As a side note, Buffett would prefer $50 billion of float at a cost of 3% to $10 billion of float at no cost.

So clearly the amount of float you get, and will get as part of the initial deal, plays a clear role.

buffett.cnbc.com/video/2000/04/…

ii) the growth of float

As a side note, Buffett would prefer $50 billion of float at a cost of 3% to $10 billion of float at no cost.

So clearly the amount of float you get, and will get as part of the initial deal, plays a clear role.

buffett.cnbc.com/video/2000/04/…

17/🧵

iii) investment returns with float

While insurer holds float on behalf of customers, it can be invested for an excess return.

How that money can be invested is regulated (see NAIC guidelines content.naic.org/sites/default/…) but there's still big differences between companies.

iii) investment returns with float

While insurer holds float on behalf of customers, it can be invested for an excess return.

How that money can be invested is regulated (see NAIC guidelines content.naic.org/sites/default/…) but there's still big differences between companies.

18/🧵

iii) investment returns with float

Most insurers must invest conservatively mainly to fixed asset classes.

E.g., Progressive $PGR had in 2020 a total of $42 billion (88%) in fixed or short-term securities, but only $5.5 billion (12%) in equities.

d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0000080661…

iii) investment returns with float

Most insurers must invest conservatively mainly to fixed asset classes.

E.g., Progressive $PGR had in 2020 a total of $42 billion (88%) in fixed or short-term securities, but only $5.5 billion (12%) in equities.

d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0000080661…

19/🧵

iii) investment returns with float

Thanks to its unique combination of insurance and unrelated operations, $BRK can invest meaningfully more in equities ($298 bln, or 66%) compared to low-risk assets ($155 bln, or 34%).

berkshirehathaway.com/2020ar/2020ar.…

arena-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/866910/37bb0e4…

iii) investment returns with float

Thanks to its unique combination of insurance and unrelated operations, $BRK can invest meaningfully more in equities ($298 bln, or 66%) compared to low-risk assets ($155 bln, or 34%).

berkshirehathaway.com/2020ar/2020ar.…

arena-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/866910/37bb0e4…

20/🧵

iii) investment returns with float

As an extreme example, Buffett bought $60 mln of float for $24 mln in Blue Chip Stamps, and used it to buy See’s Candies and 80% of Wesco for $50 mln.

These two companies alone earned Buffett $5.7 mln per year for a P/E of 24/5.7 = 4.2

iii) investment returns with float

As an extreme example, Buffett bought $60 mln of float for $24 mln in Blue Chip Stamps, and used it to buy See’s Candies and 80% of Wesco for $50 mln.

These two companies alone earned Buffett $5.7 mln per year for a P/E of 24/5.7 = 4.2

21/🧵

iii) investment returns with float

As a more normal and modern example, Progressive $PGR earned $0.9 bln with total investments of $47.5 bln for a yield of 1.9% in 2020.

d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0000080661…

iii) investment returns with float

As a more normal and modern example, Progressive $PGR earned $0.9 bln with total investments of $47.5 bln for a yield of 1.9% in 2020.

d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0000080661…

22/🧵

iii) investment returns with float

To summarize, returns should exceed risk-free returns (30-year Treasuries) but be limited by long-term equity returns.

Float is only attractive if it can be obtained at low cost, i.e. returns exceed the cost of float.

iii) investment returns with float

To summarize, returns should exceed risk-free returns (30-year Treasuries) but be limited by long-term equity returns.

Float is only attractive if it can be obtained at low cost, i.e. returns exceed the cost of float.

23/🧵

How about valuing float?

As float is other people’s money, it is accounted for as liability in the balance sheet. By now, however, we’ve learnt that it has very equity-like characteristics.

How about valuing float?

As float is other people’s money, it is accounted for as liability in the balance sheet. By now, however, we’ve learnt that it has very equity-like characteristics.

24/🧵

Holding $100 mln to invest for your own good, collecting returns as you go at no cost, should obviously be worth $100 mln for you.

So, constant, zero-cost float can be argued to be valued at least dollar to dollar.

Holding $100 mln to invest for your own good, collecting returns as you go at no cost, should obviously be worth $100 mln for you.

So, constant, zero-cost float can be argued to be valued at least dollar to dollar.

25/🧵

In such a case, if company’s book value is of any worth and it’s a world-class insurer, a simple addition of equity and float should provide a helpful guideline.

It certainly seems so by looking at Progressive $PGR and Berkshire Hathaway $BRK.

In such a case, if company’s book value is of any worth and it’s a world-class insurer, a simple addition of equity and float should provide a helpful guideline.

It certainly seems so by looking at Progressive $PGR and Berkshire Hathaway $BRK.

26/🧵

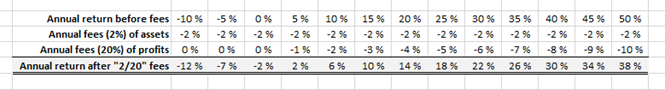

What if we change the assumptions?

Here is sensitivity analysis with the following ranges and assumptions, mid-point being baseline:

- Discount rate 1 - 7%

- Investment premium (-2) - 6%

- Float growth (-10) - 10%

- Cost of float (-5) - 5%

- 15 years (no perpetuity)

What if we change the assumptions?

Here is sensitivity analysis with the following ranges and assumptions, mid-point being baseline:

- Discount rate 1 - 7%

- Investment premium (-2) - 6%

- Float growth (-10) - 10%

- Cost of float (-5) - 5%

- 15 years (no perpetuity)

27/🧵

In a nutshell, the net present value of float is calculated through the earnings stream it allows for its holder.

Below few additional golden nuggets of wisdom regarding float.

buffett.cnbc.com/video/2001/04/…

In a nutshell, the net present value of float is calculated through the earnings stream it allows for its holder.

Below few additional golden nuggets of wisdom regarding float.

buffett.cnbc.com/video/2001/04/…

28/🧵

For an alternative approach to value float, check out Snowball author, Alice Schroeder’s groundbreaking float-based valuation for Berkshire from 1999.

arena-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/866910/37bb0e4…

For an alternative approach to value float, check out Snowball author, Alice Schroeder’s groundbreaking float-based valuation for Berkshire from 1999.

arena-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/866910/37bb0e4…

29/🧵

Great follow, @rationalwalk, wrote a bullish piece “Berkshire Insurance Subsidiaries Valuation” very close to the trough of 2009.

An absolute gem - just read it.

rationalwalk.com/berkshire-insu…

Great follow, @rationalwalk, wrote a bullish piece “Berkshire Insurance Subsidiaries Valuation” very close to the trough of 2009.

An absolute gem - just read it.

rationalwalk.com/berkshire-insu…

30/🧵

Other ways to learn more about float:

- Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letters (berkshirehathaway.com/letters/letter…)

- @BRK_student’s great new book (amazon.com/Complete-Finan…)

- @ChrisBloomstran’s client letters (semperaugustus.com/clientletter)

Other ways to learn more about float:

- Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letters (berkshirehathaway.com/letters/letter…)

- @BRK_student’s great new book (amazon.com/Complete-Finan…)

- @ChrisBloomstran’s client letters (semperaugustus.com/clientletter)

31/🧵

I’m not an insurance expert but consider that an advantage; had to oversimplify things for myself, hence hopefully been able to clarify it to you too.

For true insurance expertise, follow @SauliVilen 🇫🇮 if you’re a Finn and @ChrisBloomstran 🇺🇸 if you’re a curious human.

I’m not an insurance expert but consider that an advantage; had to oversimplify things for myself, hence hopefully been able to clarify it to you too.

For true insurance expertise, follow @SauliVilen 🇫🇮 if you’re a Finn and @ChrisBloomstran 🇺🇸 if you’re a curious human.

32/🧵

You’ve made it this far, so you seem to like threads. Me too.

Once I’ve got your attention, I’d appreciate your input on the best time to post threads like this in the future:

You’ve made it this far, so you seem to like threads. Me too.

Once I’ve got your attention, I’d appreciate your input on the best time to post threads like this in the future:

33/🧵

This was thread of insurance float – thanks for sticking with me!

If you enjoyed this, there'll be more so make sure to follow @hkeskiva. All my previous, similar threads can be found below if you still have some tea left.

Have a nice weekend 😊

This was thread of insurance float – thanks for sticking with me!

If you enjoyed this, there'll be more so make sure to follow @hkeskiva. All my previous, similar threads can be found below if you still have some tea left.

Have a nice weekend 😊

https://twitter.com/hkeskiva/status/1393471303890477056?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh