1/🧵

I like free cash flow (FCF) - who doesn’t.

But even the best of metrics can lead us astray since free cash flow can be created “out of thin air”.

In this thread we look how this can be done, and counter it with ADJUSTED FREE CASH FLOW.

Best enjoyed with a cup of tea 🫖

I like free cash flow (FCF) - who doesn’t.

But even the best of metrics can lead us astray since free cash flow can be created “out of thin air”.

In this thread we look how this can be done, and counter it with ADJUSTED FREE CASH FLOW.

Best enjoyed with a cup of tea 🫖

2/🧵

As many already know, the math of FCF is fairly simple; simply deduct operating cash flows by capital expenditure.

Free cash flow = operating cash flow – capital expenditure

In short, FCF = OCF – CAPEX

As many already know, the math of FCF is fairly simple; simply deduct operating cash flows by capital expenditure.

Free cash flow = operating cash flow – capital expenditure

In short, FCF = OCF – CAPEX

3/🧵

It’s widely acknowledged that this cash can be used by the company

i)Repurchasing shares

ii)Making acquisitions

iii)Paying out dividends

iv)Paying down financial debt

It’s widely acknowledged that this cash can be used by the company

i)Repurchasing shares

ii)Making acquisitions

iii)Paying out dividends

iv)Paying down financial debt

4/🧵

Here’s where I like to think differently.

When company A acquires company B, the buyer (A) is laying down a lump sum of CAPEX the target (B) has already spent over the years (and some in goodwill).

Hence, it’s basically no different from spending capital on CAPEX oneself.

Here’s where I like to think differently.

When company A acquires company B, the buyer (A) is laying down a lump sum of CAPEX the target (B) has already spent over the years (and some in goodwill).

Hence, it’s basically no different from spending capital on CAPEX oneself.

5/🧵

Take serial acquirer IBM that’s used $60 bln for acquisitions since 2010 – one third more than its CAPEX of $45 bln for the same period.

Despite this use of capital, IBM’s business has been on a decline since 2010:

-Revenue -26%

-Gross profit -22%

-EBIT -59%

Take serial acquirer IBM that’s used $60 bln for acquisitions since 2010 – one third more than its CAPEX of $45 bln for the same period.

Despite this use of capital, IBM’s business has been on a decline since 2010:

-Revenue -26%

-Gross profit -22%

-EBIT -59%

6/🧵

To reflect the reality and entirety of capital outlays, it could be sensible to include acquisitions in FCF. Thus, the figures for $IBM would be as follows:

Since 2010:

OCF $197.5 bln

- CAPEX $45.3 bln

= FCF $152.2 bln

- Acquisitions $60.0 bln

= FCF incl. acq $92.2 bln

To reflect the reality and entirety of capital outlays, it could be sensible to include acquisitions in FCF. Thus, the figures for $IBM would be as follows:

Since 2010:

OCF $197.5 bln

- CAPEX $45.3 bln

= FCF $152.2 bln

- Acquisitions $60.0 bln

= FCF incl. acq $92.2 bln

7/🧵

In other words, $IBM’s average FCF over 11 years has been $13.8 bln but after adjusting for acquisitions, only $8.4 bln – or 40% lower. Anyone relying on “headline FCF figures” would be terribly disappointed by such overstatement.

But Palo Alto Networks $PANW is no better.

In other words, $IBM’s average FCF over 11 years has been $13.8 bln but after adjusting for acquisitions, only $8.4 bln – or 40% lower. Anyone relying on “headline FCF figures” would be terribly disappointed by such overstatement.

But Palo Alto Networks $PANW is no better.

8/🧵

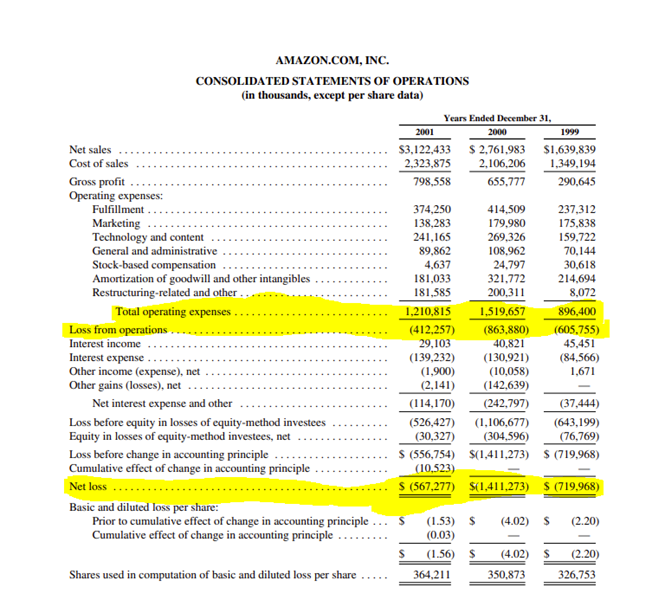

In 2020, Palo Alto Networks $PANW had the following financials that raises some questions:

- Net income -267 MUSD

- Free cash flow 821 MUSD

A difference of 1 088 MUSD?

In 2020, Palo Alto Networks $PANW had the following financials that raises some questions:

- Net income -267 MUSD

- Free cash flow 821 MUSD

A difference of 1 088 MUSD?

9/🧵

By looking at the cash flow statement, we see which items explain the difference. Mainly these are

1) ‘deferred revenue’ of 893 MUSD (typical characteristic for a SaaS company)

2) and ‘share-based compensation’ (SBC) of 658 MUSD

By looking at the cash flow statement, we see which items explain the difference. Mainly these are

1) ‘deferred revenue’ of 893 MUSD (typical characteristic for a SaaS company)

2) and ‘share-based compensation’ (SBC) of 658 MUSD

10/🧵

SBC is oftentimes considered ‘non-cash expense’, but while issued shares are handed out with the left hand, the right is buying them back from the market.

To counter this dilutive effect, Palo Alto is spending real cash to buy back shares.

Not so ‘non-cash’ anymore.

SBC is oftentimes considered ‘non-cash expense’, but while issued shares are handed out with the left hand, the right is buying them back from the market.

To counter this dilutive effect, Palo Alto is spending real cash to buy back shares.

Not so ‘non-cash’ anymore.

11/🧵

Here’s how the rabbit is pulled out of a hat and Palo Alto Networks $PANW can brag about their 30% free cash flow margins:

OCF $1,036 mln

- CAPEX $214 mln

= FCF $821 mln

- SBC $658 mln

= FCF incl. SBC $163 mln

(2020 figures)

Here’s how the rabbit is pulled out of a hat and Palo Alto Networks $PANW can brag about their 30% free cash flow margins:

OCF $1,036 mln

- CAPEX $214 mln

= FCF $821 mln

- SBC $658 mln

= FCF incl. SBC $163 mln

(2020 figures)

12/🧵

This is obviously nonsense. But the recipe for manufactured FCF figures seems to be straightforward:

1) Replace salaries with shares

2) Promote great free cash flow as an achievement

3) Quietly, counter dilution by spending cash to buy back shares

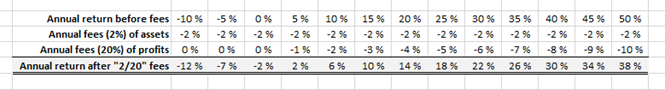

A look at Nasdaq 100:

This is obviously nonsense. But the recipe for manufactured FCF figures seems to be straightforward:

1) Replace salaries with shares

2) Promote great free cash flow as an achievement

3) Quietly, counter dilution by spending cash to buy back shares

A look at Nasdaq 100:

13/🧵

It gets uglier if we include acquisitions. In fact, much of the “FCF” ends up being a figment of imagination.

Palo Alto Networks $PANW since 2015:

OCF $6,112 mln

- CAPEX $810 mln

= FCF $5,302 mln

- SBC $3,438 mln

- Acquisitions $2,135 mln

= Adj. FCF -$271 mln

It gets uglier if we include acquisitions. In fact, much of the “FCF” ends up being a figment of imagination.

Palo Alto Networks $PANW since 2015:

OCF $6,112 mln

- CAPEX $810 mln

= FCF $5,302 mln

- SBC $3,438 mln

- Acquisitions $2,135 mln

= Adj. FCF -$271 mln

14/🧵

Of course, some are masters of M&A, creating substantial value by spending every acquisition dollar wisely on the right things at the right time.

Many times, however, M&A presents an ego boost for management and a lazy way out from underinvesting in one’s own business.

Of course, some are masters of M&A, creating substantial value by spending every acquisition dollar wisely on the right things at the right time.

Many times, however, M&A presents an ego boost for management and a lazy way out from underinvesting in one’s own business.

15/🧵

As we now have a framework to look at things differently, let’s look at #FANGMAN and a bunch of “pigs with lipstick”.

We start with #FANGMAN:

Facebook

Apple

Netflix

Google

Microsoft

Amazon

NVIDIA

As we now have a framework to look at things differently, let’s look at #FANGMAN and a bunch of “pigs with lipstick”.

We start with #FANGMAN:

Apple

Netflix

Microsoft

Amazon

NVIDIA

16/🧵

Here are the cumulative figures visualized for the first four ( $FB $AAPL $NFLX $GOOG ). I can only admire the “cleanliness” of Apple and Microsoft.

Here are the cumulative figures visualized for the first four ( $FB $AAPL $NFLX $GOOG ). I can only admire the “cleanliness” of Apple and Microsoft.

18/🧵

Here are some of the greatest share issuers in Nasdaq 100 shown through the lens of “adjusted FCF”. See how the cumulative figures differ from actual FCF.

$OKTA $TSLA $WDAY $ADBE

Here are some of the greatest share issuers in Nasdaq 100 shown through the lens of “adjusted FCF”. See how the cumulative figures differ from actual FCF.

$OKTA $TSLA $WDAY $ADBE

19/🧵

For example, take PayPal $PYPL. It’s a wonderful company, no doubt, but the financials can be misleading.

In the last 12m, OCF was $6.2 bln and CAPEX $0.9 bln for FCF of $5.3 bln.

For example, take PayPal $PYPL. It’s a wonderful company, no doubt, but the financials can be misleading.

In the last 12m, OCF was $6.2 bln and CAPEX $0.9 bln for FCF of $5.3 bln.

20/🧵

What this FCF doesn’t show, however, is that at the same time, stocks worth $1.5 bln were given to employees while $2.2 bln of stocks were repurchased from the market.

Dilution is real cost and accounting for it would reduce PayPal’s LTM FCF from $5.3 to $3.8 bln (-30%).

What this FCF doesn’t show, however, is that at the same time, stocks worth $1.5 bln were given to employees while $2.2 bln of stocks were repurchased from the market.

Dilution is real cost and accounting for it would reduce PayPal’s LTM FCF from $5.3 to $3.8 bln (-30%).

21/🧵

This approach is obviously not "the right way to look at things" but just a mindset to think differently from the crowd.

Personally, this is one thing to consider before investing. For the extreme FCF abusers, I expect some form of reckoning ahead.

This approach is obviously not "the right way to look at things" but just a mindset to think differently from the crowd.

Personally, this is one thing to consider before investing. For the extreme FCF abusers, I expect some form of reckoning ahead.

22/🧵

This was the thread of adjusted FCF - thanks for making it this far!

If you enjoyed this thread, please like/RT the first post. For more similar content, hit a follow @hkeskiva.

For great accounting-based Twitter findings, highly recommend a follow for @breadcrumbsre

This was the thread of adjusted FCF - thanks for making it this far!

If you enjoyed this thread, please like/RT the first post. For more similar content, hit a follow @hkeskiva.

For great accounting-based Twitter findings, highly recommend a follow for @breadcrumbsre

23/🧵

You may also find my earlier similar threads on business and investing from this "meta-thread" of threads.

Thanks for sticking with me! Wishing you all nice and relaxing weekend 🙂

You may also find my earlier similar threads on business and investing from this "meta-thread" of threads.

Thanks for sticking with me! Wishing you all nice and relaxing weekend 🙂

https://twitter.com/hkeskiva/status/1393471303890477056?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh